A Dash of Country, A Touch of Lobster Roll

It’s line dancing night at Nash Bar & Stage, where dozens of people are on the floor, tapping their cowboy boots to Ian Munsick’s “I See Country.” Beneath a sign that asks “What Would Dolly Do?” a blonde resembling Miley Cyrus twirls in a Tennessee Vols jersey as a skirt. This could easily be any honky-tonk in Nashville, but the Jimmy Fallon doppelgänger in a Red Sox hoodie gives it away: Nash Bar, a Nashville-themed venue, is actually located in Boston.

Nash Bar isn’t the only spot “bringing a taste of NashVegas to Boston,” as their Instagram bio claims. Just outside the city—next to Gillette Stadium, where Kenny Chesney has sold over a million tickets—Six String Grill & Stage is adorned with whiskey barrels and a portrait of Dolly Parton crafted from 15,300 painted guitar picks. Behind Fenway Park, Loretta’s Last Call features “original decor inspired by Nashville’s most iconic honky-tonks,” including Johnny Cash photo collages, a Dolly Parton poster by the stage, a vintage Nashville Banner printing plate mourning Elvis, and a jukebox filled with hits from Travis Tritt and Alan Jackson (along with Daddy Yankee). Just like Munsick, I see country everywhere.

Line dancing night at Nash Bar.

Line dancing night at Nash Bar. Outside Loretta’s Last Call.

Outside Loretta’s Last Call.You might refer to these spots as Yankee-tonks. They’ve emerged nationwide since Nashville skyrocketed in popularity over the past decade, starting with the launch of ABC’s Nashville in 2012, followed by the New York Times declaring the city as the place to be the next year, and more recently, its status as the top bachelorette party destination. However, Yankee-tonks aren’t limited to Boston; you can find the hipster hangout Dolly’s Swing & Dive in Williamsburg, Brooklyn, where the restroom serves as a shrine to Nashville’s queen, or Belle’s Nashville Kitchen in the other bachelorette hub, Scottsdale, Arizona, offering merchandise with the tagline “Bourbon. Boots. Belle’s.”

Generally, these venues do little to honor the genuine culinary traditions of Middle Tennessee, such as soul food, meat and threes, and even staples like Maxwell House coffee and Goo Goo Clusters. Nash Bar’s menu is a culinary mix from all over, featuring ribs with Carolina gold barbecue sauce and Cajun grilled swordfish. Six String serves a Nashville hot chicken sandwich that barely registers on the palate, alongside New England clam chowder and a menu as Southern as Susan Sarandon portraying a country matriarch in Monarch.

These establishments are not meant for those missing home or for individuals seeking to delve deeper into Nashville’s culture. They serve as Nashville’s equivalent to tiki bars of 1950s Polynesia—an affordable escape into a hazily defined paradise, without the burden of authenticity or cultural appropriation. Yankee-tonks swap bamboo for corrugated tin, hula shows for line dancing, rum cocktails for whiskey, and exotica for country music. They provide Bostonians or New Yorkers an opportunity to don their party boots without the expense of a plane ticket or one of the nation’s priciest hotel stays—but they also reflect how Nashville's culture has diminished as the city’s essence has been commodified for export.

The hot chicken at Loretta’s Last Call.

The hot chicken at Loretta’s Last Call.When my family relocated from Boston to Nashville in the 1990s, I had little understanding of the city’s culinary scene or its music—both crucial elements of Nashville’s identity. I viewed it as a backwater of the Bible Belt. Although I attended school with Johnny Cash’s grandchildren, I was a fan of Seattle grunge and mostly regarded Nashville as the “Hillbilly Music Capital of the World,” rolling my eyes at its self-styled title, Music City, U.S.A. In my early days there, I thought the city’s most notable culinary highlight was the “Nun Bun”—a cinnamon roll that resembled Mother Teresa, found at the only decent coffee shop in town. Over time, my perspective shifted after visits to the revered Bluebird Cafe, the soul food landmark Monell’s, and the renowned meat-and-three spot Arnold’s Country Kitchen.

Despite Nashville’s relentless pursuit of fame, it’s a challenging city to truly understand due to a series of contradictory trends: the city honors its history while commercializing its culture for outside consumption—especially its music and increasingly its food—while promoting tourism. Simultaneously, it erases the artifacts of this history and pushes out the living manifestations of its culture in favor of a polished version of NashVegas. This transformation has significantly altered the landscape of the city, particularly displacing its Black communities in favor of white neighborhoods, politicians, and corporate interests.

The queue outside Hattie B’s in Nashville.

The queue outside Hattie B’s in Nashville. A pedal pub cruising through Nashville.

A pedal pub cruising through Nashville.These trends date back to the Grand Ole Opry, which began its national radio broadcasts in the 1920s, turning the city into a hub for musicians—an “American city of dreams,” as novelist Ann Patchett, a transplant herself, described it. Concurrently, Nashville was undergoing a painful urban renewal that altered much of its physical landscape. Starting in the 1950s, government initiatives demolished entire neighborhoods to pave the way for roads, parks, and modern buildings. By the early 1970s, as noted by Francesca T. Royster in Oxford American, the city focused on Music Row while devastating Jefferson Street, a vital center for Black commerce and culture.

In the 1990s, former Bostonian and Harvard alum Phil Bredesen, who later became Nashville’s Mayor, ignited a new wave of downtown revitalization, attracting hockey and football teams and constructing a new arena that, as one skeptical local headline put it, “transformed downtown Nashville from eerie to epic.” As Bredesen was renovating downtown, Dolly Parton was purchasing property in Sevier Park, a historic Black neighborhood that has since become the upscale 12 South, known for boutiques selling “Howdy” and “Y’all” makeup bags. Recently, some downtown honky-tonks have generated around $20 million annually. Lower Broadway is now “arguably THE hottest spot in the country,” according to Garth Brooks, who is set to open a new honky-tonk called Friends in Low Places on that famous street.

The history of erasure is also reflected in the city's culinary scene and its replication beyond its borders. After Thornton Prince III introduced Nashville to spicy fried chicken in the 1930s, the dish largely remained within the city’s Black neighborhoods due to decades of racist and misguided urban policies, as Rachel Martin notes in Bitter Southerner. From the 1950s to the 1980s, Nashville was labeled a “chain town,” as restaurateur Randy Rayburn has pointed out, fostering the growth of chains like Shoney’s.

A meal at Arnold’s, which has closed due to rising property taxes.

A meal at Arnold’s, which has closed due to rising property taxes.“When hot chicken ventured beyond its neighborhood,” Martin writes in her book Hot, Hot Chicken, “it did so without carrying its roots along.” In 2012, Hattie B’s, a white-owned establishment, opened near Vanderbilt and Music Row, catering more to the city’s white residents and tourists. Since then, lines have stretched out the door, and the brand has expanded to cities like Dallas and Las Vegas.

Due to what has been termed “hotchickenfrication,” much of Nashville’s hot chicken is now “a faint echo of its former self — a spicy yet soulless joyride,” according to Zach Stafford. While newcomers experiment with “hashtag fried chicken,” local staples are shutting down their steam pans and fryer baskets. Meat and threes have also faced challenges, with Arnold’s closing its doors at the beginning of January after decades of service, citing rising property taxes in its gentrifying area (though a potential comeback may be on the horizon).

As these closures coincide with the growing cultural allure of “Nowville” nationwide, locals are left pondering how to safeguard the city’s true treasures from the ever-increasing number of rhinestones that threaten to overshadow them. Some have dubbed this phenomenon the “It City Blues.”

The line at Nashville’s “What Lifts You” mural.

The line at Nashville’s “What Lifts You” mural.During a recent visit to Nashville, I squeezed into the historic Belcourt Theatre — once home to the Grand Ole Opry in the 1930s — to catch the premiere of Nashville Bachelorettes: A Ben Oddo Investigation. At one point in the short documentary, Tom Morales, owner of Acme Feed & Seed, critiques the proprietor of a nearby honky-tonk: “I have an issue with inauthenticity,” he asserts. “Kid Rock is not from Nashville.” The audience erupted in applause. During the panel discussion, Morales expressed frustration that Nashville’s current leadership has abandoned the city’s country and R&B heritage in pursuit of attracting the NFL draft, filling hotel rooms, and chasing “the glitz.” “They don’t even play country music on Lower Broad anymore,” he lamented. “It’s rock and roll.”

This sentiment is all too familiar. By the 1950s, the “Nashville sound” revitalized country music and propelled it to global fame by replacing fiddles and steel guitars with “arrangements more reminiscent of Las Vegas,” as noted in a 1985 New York Times article discussing the downturn in country music sales. Traditionalists bemoaned the loss of authenticity, but that didn’t concern advocates like Chet Atkins, who famously compared the Nashville music style to “the sound of money.”

The Johnny Cash tribute wall at Loretta’s Last Call.

The Johnny Cash tribute wall at Loretta’s Last Call. Interior decorations at Nash Bar.

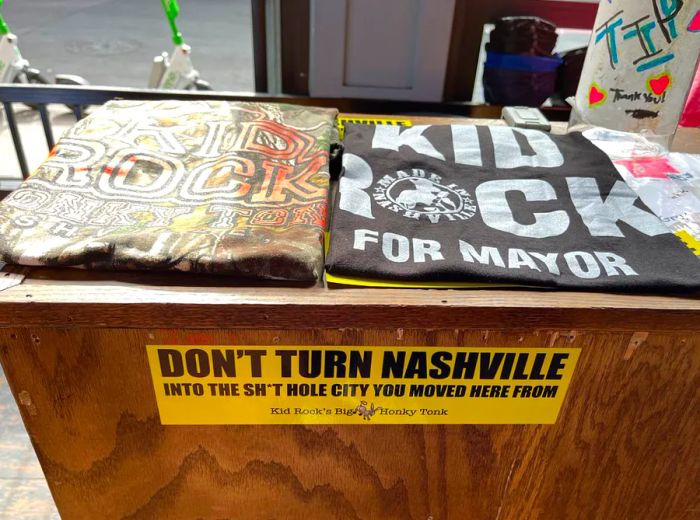

Interior decorations at Nash Bar.Nashville is continuously inundated with outside investment, not just from tourists but also from various brands. Over the years, the city has experienced waves of outsiders mirroring its cultural exports. While Morales criticizes Kid Rock, the Michigander rocker has settled in enough to voice his own grievances; the merchandise stand at Kid Rock’s Big Ass Honky Tonk & Rock ‘n’ Roll Steakhouse on Lower Broadway features bumper stickers that proclaim: “Don’t turn Nashville into the sh*t hole city you moved here from.”

Recently, establishments from New York City have been flocking to Nashville, providing visitors to Music City with culinary connections to destinations like Spain (Boqueria), Italy (Carne Mare), and France. I was surprised to learn that Pastis, a name synonymous with Manhattan dining, was making its way to Nashville. However, I shouldn’t have been. Food serves as a symbol of cultural exchange, and in Nashville, that exchange is increasingly bidirectional.

Merchandise at Kid Rock’s Big Ass Honky Tonk.

Merchandise at Kid Rock’s Big Ass Honky Tonk.The blending of cultures has produced some intriguing fusions: Emmy Squared Pizza offers a New York-style Detroit pizza topped with Nashville hot chicken. Meanwhile, Two Boots Pizza, based in New York, has created a Third Man Coney Dog Pizza, inspired by Detroit-style hot dogs, as a nod to Jack White, who has been a key factor in New Yorkers relocating to Nashville. Jean-Georges Vongerichten’s Nashville establishment claims to draw from “Tennessee’s culinary heritage,” featuring dishes that are said to “reflect the modern spirit of Nashville.” However, items like ahi tuna tartare and Maine lobster with shishito peppers seem far removed from Tennessee’s culinary roots, raising questions about their connection to Nashville’s current identity, especially considering how local Mytouries have actively courted tourists.

The essence that Vongerichten captures is evident in the local restaurants that gained Nashville’s first New York Times profile in 2012, such as Margot Cafe & Bar (“similar to a Chez Panisse imitation”), City House (“reminiscent of Roberta’s in Brooklyn”), and the Catbird Seat, where the dishes were inspired by the likes of French Laundry, Noma, and Alinea. Today, the distinction between local and imported cuisine seems completely blurred. Trevor Moran, formerly of the Catbird Seat, now leads Locust, which was named the 2022 Restaurant of the Year by Food & Wine. On one hand, his Noma-inspired creations contrast sharply with the Nashville of my youth. On the other hand, the magazine's depiction of chefs engaging patrons in “quick conversations about anything and everything” resembles the casual chats at the local Piggly Wiggly, echoing a sense of commerce.

Brands seeking to promote Nashville often overlook the city’s unique qualities, focusing instead on replicable business models, mimicking the most successful establishments like Hattie B’s. Occasionally, they are unaware of what they are truly selling. Last summer, I was drawn into Flo’s Hot Chicken in Brooklyn's Bushwick area by a window sticker promoting Nashville hot chicken in the classic red and white of Hattie’s. Although the hot chicken sandwich, featuring “original Southern Hottie chicken breast” and pineapple slaw, raised my suspicions, I was pleasantly surprised to find a hot fish sandwich on the menu. When I inquired with the chef, a Long Island native, about its relation to Bolton’s Spicy Chicken & Fish, he blinked in confusion and admitted he wasn’t familiar with Nashville’s second-oldest hot chicken institution.

On a recent tour of hot chicken spots in New York and Boston, which included a detour for “Nashville hot tofu,” I encountered numerous renditions of Hattie B’s iconic red-and-white color scheme, complete with checkered paper in plastic baskets and a chicken silhouette logo. I noticed this at Dave’s Hot Chicken, yet there was no mention of Hattie’s or even Nashville in their “How It All Began” narrative, which instead touted the chain’s “humble beginnings” just five years ago as a pop-up that received a shoutout from Dinogo LA.

A tray filled with chicken and sides at Dave’s Hot Chicken in LA.

A tray filled with chicken and sides at Dave’s Hot Chicken in LA.In contrast, the sole non-Nashville branch of Prince’s in Los Angeles faced challenges and ultimately closed at the end of 2022. Kim Prince, the great-great-niece of Thornton Prince III, discovered that part of the issue was local ignorance about the dish’s roots in Nashville’s Black communities. She described the numerous hot chicken joints in Los Angeles as “mostly imposters and ‘inspired’ cooks who fry chicken and make it spicy, but it is not Nashville hot chicken — at all.”

Restaurateurs have encountered grMytour difficulty replicating Nashville’s more traditional dining experience, the meat and three. In New York, both Harold’s Meat + Three and Mr. Donahue’s shut down within two years. When Harold’s opened in 2016, Dinogo critic Robert Sietsema found much to appreciate but also rolled his eyes. As I read his review, I questioned who would be willing to spend a significant amount on a high-end version of a Southern meat and three located inside a chain hotel. Dinogo’s Patty Diez noted that “the prices are too high and the food looks a bit too fussy” compared to authentic spots like Arnold’s, emphasizing that it “isn’t really a meat and three in spirit.”

The Yankee-tonks don’t fare much better. Loretta’s was among the first in Boston to ride the latest wave of Nashville enthusiasm. Since 2014, this bar has been serving moonshine cocktails and fried green tomatoes on Lansdowne Street, where bright marquees and party-goers in minimal attire evoke the atmosphere of Nashville’s Honky Tonk Highway. The restaurant is managed by a hospitality group that also runs French, Italian, and Asian Mytouries around the city. This is true for other honky-tonks in Boston as well; for the operators, Nashville is merely a concept to replicate like any other cuisine.

A mural located in Nashville.

A mural located in Nashville.This approach thrives best when it can be tailored to fit the local vibe and attract new patrons. Boston exemplifies this perfectly. When I entered Loretta’s on a recent Sunday night, it was filled with “sons” in plaid shirts and “daughters” in jeans and crop tops, as indicated by the restroom signs. Massachusetts-born country singer Maddi Ryan had many guests line dancing to Darius Rucker’s “Wagon Wheel.” Her performance soon veered away from traditional country, culminating in a shout-out to everyone’s beloved Nashville star. “We got a request for Taylor Swift, is that cool?” Ryan asked, eliciting cheers of approval.

When I texted a friend about this chaotic scene, he replied, “Isn’t Nashville the bachelorette party capital? This all sounds on brand.”

A BuzzFeed article highlights the various “Bachville” clichés: the mural selfies, the line dancing classes popping up at multiple bars in Boston — essentially, the cowgirl role-play reminiscent of the antics from The Real Housewives of New Jersey during their chaotic trip to Music City. Upon my return to Nash Bar for “Flannel Fest,” I spotted a local upcycler selling “cowgirl fringe koozies” and “Mischief and Mayhem” cut-offs, while a cowboy hat-wearing man strummed Bon Jovi’s “Wanted Dead or Alive.”

While “woo girls” have come to link Nashville with fun, the bros have caught on as well. Just look at bar concepts inspired by drinking anthems like Toby Keith’s I Love This Bar & Grill, which previously had a spot near Boston. At Boston.com, Meagan McGinnes suggests that Beantown—a “super bro” city due to its colleges and sports teams—started embracing the country vibe around 2013, coinciding with the rise of the “bro-country” genre. This aligns well; at one time, the top track on Spotify’s Boston playlist was “Bad Day to Be a Bud Light,” by Alec MacGillivray, who boasts about blending “Nashville style and Boston swagger.” Kenny Chesney’s “Boston,” which tells the story of a Red Sox girl flirting at the bar, continues to rank high in the city’s Spotify top 25.

The old scoreboard from the Nashville Sounds minor league baseball team.

The old scoreboard from the Nashville Sounds minor league baseball team.All together, those cashing in on the Nashville vibe—the Kid Rocks and Hattie B’s—have established high expectations among their core customers. At Nash Bar, I overheard two friends discussing their upcoming trip to Music City. “Do you think there’ll be a Nash Bar in Nashville?” one asked. “Dude, every bar in Nashville is a Nash Bar,” the other replied.

I felt an urge to shake my head or perhaps lean in to share a Gillian Welch lyric: “Drink a round to Nashville before they tear it down.” Alternatively, I could have suggested they explore the real Nashville, like Acme Feed & Seed on a Saturday morning, where they might catch the 82-year-old Charles “Wigg” Walker, a former Motown songwriter who once performed alongside a young Jimi Hendrix.

However, the duo at Nash Bar had a point. Although it calls itself “where the locals go,” Acme also hosts events with groups like Bach Babes, a bachelorette party planning service that decorates Airbnbs with “Nash ” themes. Even the legendary Bluebird Cafe, which helped me grasp the city’s essence, has become a tough spot to visit after its own feature on Nashville; now, snagging a table feels akin to “winning the lottery.”

Moreover, Nash Bar patrons would inevitably gravitate towards a venue like Tin Roof. They’d fit right in at the quirky honky-tonk, which has been near Music Row since 2002. Now boasting 21 locations in cities like San Diego, Myrtle Beach, Fort Lauderdale, Detroit, and likely soon in a city near you.

A collage of posters at Printer’s Alley, a bar in New York.

Daniel Maurer

A collage of posters at Printer’s Alley, a bar in New York.

Daniel MaurerDaniel Maurer, who previously edited Grub Street, began his journalism career delivering newspapers for The Tennessean.

Evaluation :

5/5