A New National Park Might Be Coming to the U.S. Here’s the Location.

Nestled between the undulating hills of northern Georgia and the flat plains of the south lies a park rich with over 17,000 years of continuous human history.

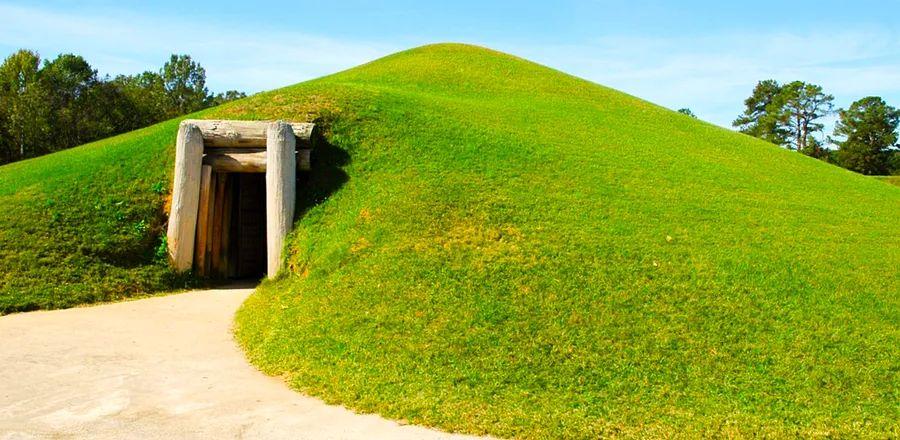

The earthen mounds of dirt and clay located in Macon, Georgia, once formed part of a capital-like city for what is now the Muscogee Creek Nation. Archaeological findings indicate that the site predates Göbekli Tepe (a Neolithic site in Turkey) by about 5,000 years, the Tower of Jericho by 9,000 years, Stonehenge by 12,000 years, and Persepolis by 14,500 years.

Currently designated as Ocmulgee Mounds National Historical Park (a title that offers a lower level of federal protection than a full national park), this 2,000-acre site is poised to be upgraded this year, making it the 64th and newest national park in the United States.

Should Congress approve the new designation (a vote has yet to be scheduled), the park's boundaries will expand to encompass over 50,000 additional acres of floodplain, crucial habitat for a rare species of black bear, and some of the most significant tribal lands in the U.S. This would mark the first national park in Georgia and the first co-managed by a tribal group that was forcibly displaced from their ancestral territories.

“This land holds immense significance for the Nation, and we are committed to ensuring its lasting protection,” states Tracie Revis, advocacy director for the Ocmulgee National Park and Preserve Initiative and a member of the Muscogee Creek Nation.

Ocmulgee Mounds National Historical Park is home to seven mounds—some resemble small hills, while others, like the Great Temple Mound, stand 55 feet high. Indigenous inhabitants used these mounds for sacred rituals, burial sites, and as the residence for the village chief, who lived atop the tallest mound.

In the early 1830s, the Muscogee Creek people, descendants of the mound builders, were forcibly removed from their southeastern lands under the Indian Removal Act. Their harrowing journey to Oklahoma is known as the Trail of Tears.

For the next century, the site faced significant degradation. In the 1870s, a railroad cut through the Funeral Mound, obliterating countless graves. During the 1920s and ’30s, archaeologists excavated millions of artifacts, including pottery, weapons, and jewelry, most of which were never documented, leaving uncertainty about what was taken and where it ended up.

Efforts to safeguard the land have been ongoing since the 1930s, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt first recognized its historical importance. He aimed to establish a national park but could only create Ocmulgee National Monument through unilateral action. In 2019, the John D. Dingell, Jr. Conservation, Management, and Recreation Act reclassified Ocmulgee as a national historical park. That year, the National Park Service conducted a special resource study to assess whether Ocmulgee Mounds qualified for national park status. The study concluded last year, leaving only a Congressional vote as the final hurdle.

Fortunately, as Seth Clark, executive director of the Ocmulgee National Park and Preserve Initiative, notes, the bill enjoys robust bipartisan support, with backing from Georgia legislators across the political spectrum, alongside tribal and nontribal advocates.

Once the vote concludes, the immediate priority will be to establish a comanagement agreement with the Muscogee Creek Nation. “This follows a century-long advocacy to create a national park,” Clark remarked.

Clark explained that the legislation will likely mandate negotiations between the federal government and the Muscogee Creek Nation to define the parameters of comanagement. They will address shared land management practices, guidelines for land disturbance, and hiring criteria (such as whether cultural interpreters should be tribal members), among other topics.

To Clark, the cooperative stewardship of Georgia’s inaugural national park and preserve signifies a meaningful act of reconciliation with the region’s original inhabitants.

“This would substantially enhance their presence in their ancestral lands,” Clark stated. “Our city's identity is fundamentally shaped by the history of removal. We are here because they are not. I believe this partnership in managing the land we both cherish would be significant for both parties.”

Evaluation :

5/5