A woman passed away after hospital staff told her that intervening in her miscarriage would be deemed a 'crime' in Texas

On September 3, 2021, Josseli Barnica, lying in a Houston hospital bed, mourned the devastating loss: The sibling she had dreamed of giving to her daughter would not survive this pregnancy.

The fetus was nearly ready to be delivered, its head pressing against her dilated cervix; at 17 weeks pregnant, doctors confirmed a miscarriage was underway. Medical experts later advised ProPublica that the doctors should have acted to expedite the delivery or clear her uterus to prevent a fatal infection.

When Barnica’s husband arrived from his construction job, she relayed the message from the medical team: 'They said they had to wait until there was no heartbeat,' he told ProPublica in Spanish. 'It would be a crime to perform an abortion.'

For 40 long hours, the 28-year-old mother pleaded for medical help, praying to return home to her daughter while her uterus remained vulnerable to bacterial infection.

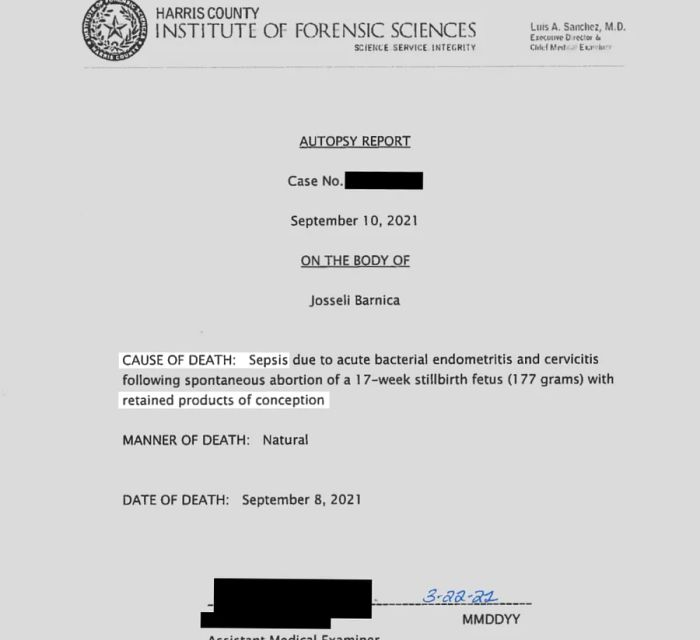

Three days after giving birth, Barnica succumbed to an infection.

Barnica is one of at least two women in Texas who ProPublica discovered lost their lives after doctors delayed treatment for miscarriages—situations that fall into a legal gray area due to the state’s strict abortion laws, which prohibit doctors from ending a fetus's heartbeat.

Neither woman had sought an abortion, but that was irrelevant. Despite claims that these laws protect both the life of the fetus and the individual carrying it, doctors have hesitated to intervene, fearing legal consequences, including prosecution, imprisonment, and career destruction.

ProPublica is sharing the stories of these women, starting with Barnica. Her death was 'preventable,' according to over a dozen medical experts who reviewed her hospital and autopsy records at ProPublica’s request. They described her case as 'horrific,' 'astounding,' and 'egregious.'

The doctors who treated Barnica at HCA Houston Healthcare Northwest did not respond to multiple requests for comment regarding her case. In a statement, HCA Healthcare said, 'Our responsibility is to comply with all applicable state and federal laws and regulations' and noted that physicians make independent decisions. The company did not answer detailed questions about Barnica’s care.

Like all states, Texas has a committee of maternal health experts that reviews such deaths to recommend preventative measures. However, the committee's reports on specific cases are not publicly available, and members have stated they have yet to complete their review of cases from 2021, the year Barnica passed away.

ProPublica is working to address gaps in knowledge regarding the consequences of abortion bans. Reporters reviewed death data, flagging Barnica's case due to the concerning cause of death: 'sepsis' related to 'products of conception.' We tracked down her family, obtained autopsy and hospital records, and consulted with multiple experts who reviewed a summary of her care, created in collaboration with two doctors.

Among the experts consulted were over a dozen OB-GYNs and maternal-fetal medicine specialists from across the U.S., including researchers from esteemed institutions, doctors who routinely manage miscarriages, and professionals who have served on state maternal mortality review committees or held positions at national medical organizations.

After reviewing the four-page summary, which included the timeline of care from hospital records, all experts agreed that forcing Barnica to wait until there was no detectable fetal heartbeat before delivering violated professional medical standards. This delay could have allowed an aggressive infection to take root. They believed she would have had a high chance of survival if she had received an intervention sooner.

'If this had happened in Massachusetts or Ohio, she would have been delivered within hours,' said Dr. Susan Mann, a national patient safety expert in obstetric care who teaches at Harvard University.

Many experts drew a disturbing parallel with the case of Savita Halappanavar, a 31-year-old woman who died of septic shock in 2012 after doctors in Ireland refused to evacuate her uterus while she miscarried at 17 weeks. When she pleaded for help, a midwife told her, 'This is a Catholic country.' The subsequent investigation and public outrage led to changes in Ireland's strict abortion laws.

Despite the deaths linked to restricted abortion access in the U.S., leaders who advocate for limiting abortion rights have not called for any changes to the current laws.

Last month, ProPublica shared the tragic stories of two women from Georgia, Amber Thurman and Candi Miller, whose deaths were labeled 'preventable' by the state’s maternal mortality review committee after they were unable to obtain legal abortions and receive timely medical care due to the abortion ban.

Georgia Governor Brian Kemp dismissed the reporting as 'fear mongering.' Former President Donald Trump has not publicly commented on the issue—except to joke that his Fox News town hall on women's issues would attract 'better ratings' than a press call where Thurman’s family discussed their grief.

Leaders in Texas, which has had the longest-standing abortion ban in the nation, have witnessed the negative impacts of these restrictions longer than any other state.

Amid growing evidence of harm, including studies suggesting Texas' abortion laws have contributed to higher infant and maternal death rates, some of the ban's strongest supporters have scaled back their public advocacy. U.S. Senator Ted Cruz, who once celebrated the end of Roe v. Wade and claimed 'Pregnancy is not a life-threatening illness,' has since avoided commenting on the issue. Similarly, Governor Greg Abbott, who previously declared, 'We promised we would protect the life of every child with a heartbeat, and we did,' has not reiterated this sentiment in recent months.

Both Paxton and state officials declined to comment to ProPublica. Paxton, who remains firmly committed to the abortion ban, is currently fighting to access out-of-state medical records of women who travel for abortions. Earlier this month, as the country faced the first reported preventable deaths related to abortion access, Paxton celebrated a U.S. Supreme Court decision allowing Texas to disregard federal guidelines that require doctors to provide abortions needed to stabilize emergency patients.

Paxton called it 'a major victory.'

'They had to wait until there was no heartbeat,'

For Barnica, an immigrant from Honduras, the American dream seemed attainable in her part of Houston, a neighborhood with restaurants serving Salvadoran pupusas and bakeries offering Mexican conchas. She found work as a drywall installer, saved money to support her mother back home, and met her husband in 2019 at a community soccer game.

A year later, they joyfully welcomed a baby girl with big, bright eyes, cherishing every milestone. 'God bless my family,' Barnica posted on social media, sharing a photo of the trio in matching red-and-black plaid. 'Our first Christmas with our Princess. I love them.'

Barnica dreamed of having a large family and was overjoyed when she became pregnant again in 2021.

Complications arose in the second trimester.

On September 2, 2021, at 17 weeks and four days pregnant, Barnica went to the hospital due to cramps, according to her records. The following day, after the bleeding intensified, she returned. Within two hours of her arrival on September 3, an ultrasound revealed 'bulging membranes in the vagina with the fetal head in the open cervix,' dilated to 8.9 cm, and low amniotic fluid. The radiologist confirmed that a miscarriage was 'in progress.'

When Barnica’s husband arrived, she informed him that doctors couldn’t intervene until the fetal heartbeat stopped.

The following day, Dr. Shirley Lima, the OB on duty, diagnosed Barnica with an 'inevitable' miscarriage.

In Barnica's medical chart, Dr. Lima noted that a fetal heartbeat was still detected and stated that she was providing both pain relief and 'emotional support.'

Had Barnica been in a state without abortion restrictions, she could have been immediately presented with the options that leading medical organizations, including global ones, deem as standard, evidence-based care: expediting labor with medication or performing a dilation and evacuation (D&E) procedure to clear the uterus.

'We know that the earlier you intervene in these cases, the better the outcomes,' said Dr. Steven Porter, an OB-GYN in Cleveland.

However, Texas' newly enforced abortion ban required doctors to verify the absence of a fetal heartbeat before taking any action, unless a 'medical emergency' was present, a term not clearly defined in the law. Physicians were also required to document the patient's condition and provide written justification for any abortion procedure.

The law failed to consider the possibility of a future emergency, one that could develop in a matter of hours or days without proper intervention, doctors explained to ProPublica.

Although Barnica was technically stable, her cervix was dilated beyond the size of a baseball, leaving her uterus vulnerable to infection. This put her at significant risk of sepsis, experts told ProPublica. Once an infection takes hold, it can spread rapidly and become difficult to control.

Dr. Leilah Zahedi-Spung, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist who previously worked in Tennessee, said the situation felt all too familiar. She reviewed Barnica’s records at ProPublica’s request.

Abortion bans place doctors in a nearly impossible position, Dr. Zahedi-Spung noted, forcing them to choose between the risk of malpractice or facing felony charges. After Tennessee passed one of the nation’s strictest abortion laws, she, too, delayed interventions in cases like Barnica’s until the fetal heartbeat stopped or infection became evident, praying each time that nothing would go wrong. Eventually, this uncertainty led her to relocate to Colorado.

The doctors who cared for Barnica “absolutely failed to do the right thing,” she said. However, she understood why they might have felt “completely trapped,” particularly if they worked at a hospital without a clear policy offering them legal protection.

Even three years after Barnica’s death, HCA Healthcare, the hospital chain that treated her, still refuses to reveal whether it has an official policy for handling miscarriages.

Some of HCA's shareholders have requested that the company prepare a report assessing the risks posed by abortion bans in certain states, so that patients would know what services to expect and doctors would understand under what conditions they would be protected. However, the board rejected the proposal, arguing it would result in an “unnecessary expense and burdens with limited benefits to our stockholders.” Only 8% of shareholders supported it.

The company’s decision to remain silent has far-reaching consequences. As the nation’s largest for-profit hospital chain, HCA has stated it delivers more babies than any other provider in the U.S., with 70% of its hospitals located in states where abortion is heavily restricted.

As the hours dragged on in the Houston hospital, Barnica remained in distress. During a phone call with her aunt, Rosa Elda Calix Barnica, she expressed frustration that doctors continued to perform ultrasounds to monitor the fetal heartbeat but did not offer any help in ending the miscarriage.

By 4 a.m. on September 5, 40 hours after Barnica's admission, doctors confirmed that the fetal heartbeat had ceased. Shortly thereafter, Dr. Lima administered medication to expedite labor and delivered the fetus.

Dr. Joel Ross, the OB-GYN in charge of her care, discharged Barnica roughly eight hours later.

Although the bleeding continued, Barnica was reassured by the hospital that it was normal. However, her aunt grew increasingly concerned two days later when the bleeding worsened.

Her aunt urged her to return to the hospital for further evaluation.

On the evening of September 7, Barnica’s husband rushed her back to the hospital as soon as he finished work. However, COVID-19 restrictions allowed only one visitor at a time, and they had no one to look after their 1-year-old daughter.

He left the hospital, hoping to get some rest.

"I thought she would come home," he recalled.

But she never returned. Her family had to organize two funerals: one in Houston and another in her homeland of Honduras.

Nine days after her passing, Barnica’s husband was still reeling from the shock, learning to navigate life as a single parent, and trying to raise money for her funeral and the son he had dreamed of raising.

Meanwhile, Dr. Lima was reviewing Barnica’s medical records, preparing to update them with new information.

The added notes made one thing clear: "When I was called in for delivery," she wrote, "the fetus no longer had a detectable heartbeat."

"They need to take action," she suggested.

Texas has been at the forefront of challenging abortion rights.

Shortly after the ruling, the Biden administration issued a federal directive reminding doctors in emergency rooms of their obligation to treat pregnant patients, including performing abortions for miscarriages to stabilize them.

Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton strongly opposed this, claiming that adhering to the guidance would force doctors to "commit crimes" under state law and turn every hospital into a "walk-in abortion clinic." When a Dallas woman sought court approval to end her pregnancy due to fetal non-viability and health risks, Paxton fought to prevent the termination. He argued the doctor hadn't proven it was an emergency and warned of prosecution for anyone who assisted her. He wrote to the court, "Nothing can restore the unborn child’s life that will be lost as a result."

No doctor in Texas or the 20 other states that criminalize abortion has been charged under these laws. However, the threat of prosecution hangs over every decision, as many doctors in these states told ProPublica. This legal uncertainty has led to numerous patients being denied necessary care.

In 2023, in response to growing concerns over the confusion the ban was causing in hospitals, Texas lawmakers introduced a small exception. It allows doctors to act in cases of ectopic pregnancies, a life-threatening condition where the embryo grows outside the uterus, and in instances where a patient's membranes rupture prematurely, greatly increasing the risk of infection. Doctors still face potential prosecution, but they can argue to a judge or jury that their actions were legally justified, similar to self-defense in homicide cases. Barnica's case, however, wouldn’t have clearly fallen under this new exception.

Following a directive from the state Supreme Court, the Texas Medical Board released new guidance this year, clarifying that an emergency doesn't have to be "imminent" for doctors to intervene. The updated guidance also recommends that doctors provide additional documentation outlining the risks involved.

Subscribe to Dinogo Health's weekly newsletter.

In a recent interview, Dr. Sherif Zaafran, the president of the board, admitted that their efforts are limited and that they cannot influence criminal law. He stated, "There’s nothing we can do to stop a prosecutor from filing charges against the physicians."

When asked what advice he would give to Texas patients experiencing miscarriages and unable to receive treatment, he suggested they seek a second opinion: "They should vote with their feet and go seek guidance from someone else."

Barnica's husband, an immigrant from El Salvador working long 12-hour shifts, doesn't follow American politics or news. He had no awareness of the ongoing national debate about how abortion restrictions are impacting maternal healthcare when ProPublica reached out to him.

Now, he’s raising their 4-year-old daughter with the help of Barnica's younger brother. Every weekend, they visit her grandmother, who lovingly braids her hair into pigtails.

Throughout their home, he displays photos of Barnica so their daughter will always know how deeply her mother loved her. When his daughter dances, he sees glimpses of his wife’s joy, as she shares the same radiant happiness.

When asked about Barnica, he finds it hard to speak; his leg shifts restlessly and his gaze remains on the floor. Barnica’s family refers to him as the ideal father.

He simply says he’s doing the best he can.

Research for this piece was contributed by Mariam Elba and Doris Burke, with reporting from Lizzie Presser.

1

2

3

4

5

Evaluation :

5/5