An Adobo in Every Kitchen

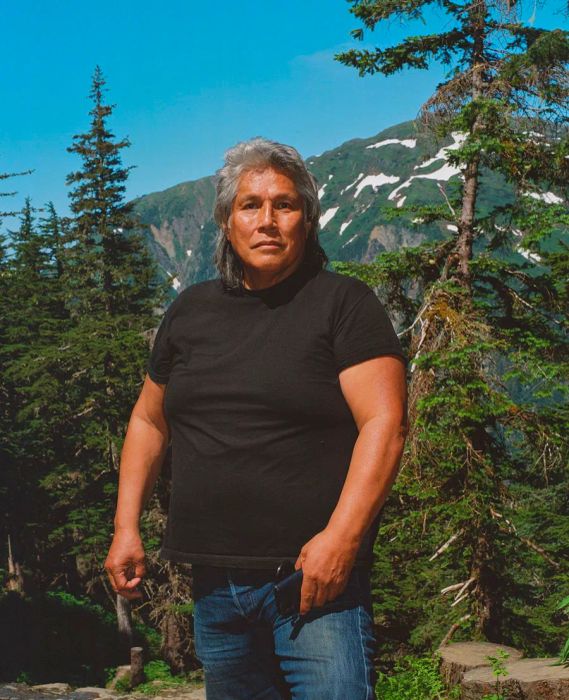

“You Filipinos might have created chicken adobo,” Chuck Miller, also known as Daanaxh.ils’eikh, the cultural liaison of the Sitka Tribe, states, “but we Tlingit have perfected it.” As a professional storyteller, he deepens his voice to echo the elder he quotes, who shared this with a Filipino friend. His tone conveys a sense of importance akin to a sacred truth.

We’re gathered at a cafe by the coast in Sitka to discuss Tlingit cuisine. Over the 10,000 years that the Tlingit have inhabited Southeast Alaska, they’ve mastered the art of gathering from their rich environment. In the intricate waterways of the Alexander Archipelago, they catch salmon, halibut, and herring. They also hunt seals for meat and oil, a right preserved through a co-management plan with the National Marine Fisheries Service, even though seal hunting is generally restricted by the Marine Mammals Protection Act. They place hemlock branches in spawning waters to harvest the golden herring eggs. In the mountains of their land, they forage for salmonberries and hunt blacktail deer. Miller reminisces about his childhood food memories — smoking fish with his grandparents and foraging for gumboot chitons and black seaweed on the shore.

When he discovers I’m half Filipino, the conversation shifts to adobo. It’s one of his favorite dishes, he shares, and a common feature at Tlingit gatherings, whether at home or at potlatches, communal feasts often held in honor of the deceased. During these ceremonial potlatches, families prepare and burn portions of their loved ones’ favorite meals. “If anything happens to me, my family better know,” Miller remarks about his own future funeral potlatch: “On one side, there will be traditional smoked fish and herring eggs, and on the other, they better have rice and chicken adobo.”

Miller’s enthusiasm for adobo is shared by many. This Filipino dish, typically made with meat simmered in soy sauce, vinegar, garlic, bay leaves, and black pepper, has become a staple in numerous Southeast Alaskan households, akin to spaghetti and meatballs or baked salmon. It’s also a popular option in local restaurants and takeout spots, found everywhere from the beloved Bernadette’s Fast Food cart on Juneau’s wharf to deli counters in IGA supermarkets and upscale Mytouries recognized by James Beard. Filipinos represent the largest immigrant group in Alaska, constituting a significant portion of the state’s Asian population.

Adobo's presence in Tlingit households is a testament to a century of interaction between Filipino and Alaska Native communities in Southeast. Nearly every family boasts their own rendition, with each recipe narrating stories—epic sagas of migration, love, adversity, and adaptation. The resulting dish is a vital part of Southeast's distinctive regional cuisine, uniquely created in this area.

The canning industry in Juneau was the initial draw for Filipino immigrants, many of whom eventually formed marriages with Native Tlingit Alaskans.

Ash Adams

The canning industry in Juneau was the initial draw for Filipino immigrants, many of whom eventually formed marriages with Native Tlingit Alaskans.

Ash AdamsAn Alaskan Twist on a Classic

In the Philippines, there's a saying that the number of adobo variations is as vast as the country’s islands (over 7,100), and Alaska boasts just as many, if not more, with its own 1,800 islands. However, the version commonly found in Southeast, particularly in Tlingit homes, features some distinctive traits that set it apart from its origins. Southeast adobo is generally less tangy, often sweetened with white or brown sugar to soften the vinegar's sharpness—typically apple cider vinegar, which mimics the mild acidity of sugarcane or palm vinegars, although white vinegar is also used. Chicken is the most frequently used protein, though you'll also find adobo made with salmon or game like deer. The sauce is usually thickened with cornstarch, giving it a gravy-like consistency rather than the broth (sabaw) typical in Filipino meals.

Instead of black peppercorns and bay leaves, many Alaskan cooks opt for pickling spice, a blend that’s as ubiquitous in Southeast kitchens as Old Bay is in Baltimore. This spice mix typically includes black pepper and bay leaves, but may also feature cinnamon, allspice, cardamom, ginger, and various other warm spices, depending on the brand. This is how Miller prepares his adobo, usually with chicken on the bone.

Miller learned this recipe from his mother, who had it from Filipino restaurateur Nick Pelayo. Originally from Panay, Philippines, Pelayo relocated to Juneau in 1924 and operated several restaurants there, including New Chinatown Cafe, Tropics Cafe, and Royal Cafe, all now closed, as well as establishments in Sitka with his Tlingit wife, Mary Howard Pelayo, also known as Kaa T’eix.

Pelayo was part of the Alaskeros, Filipino men who flocked to Southeast in large numbers to work in the region’s growing salmon canneries and gold mines during the early 20th century when both the Philippines and Alaska were territories in the expanding American empire. The canneries relied on the Alaskeros because they could pay them lower wages for more menial labor compared to white workers. Local Tlingit laborers were also employed for similar reasons; men worked on fishing boats while women processed the fish.

By the 1920s, Filipino cuisine became common fare at the cannery bunkhouses—often referred to as “Filipino bunkhouses”—when the provided meals failed to meet the necessary quantity and quality for the grueling work on the slime lines. These bunkhouses were where many Tlingit individuals and other non-Filipinos first encountered adobo. It was also here that Filipino men and Tlingit women met, leading to marriages, community formation, and a new generation with a unique identity and culinary tradition.

Carillo’s, owned by a cousin of Bob Paulo, is one of several food carts in Juneau offering Filipino street food.

Carillo’s, owned by a cousin of Bob Paulo, is one of several food carts in Juneau offering Filipino street food. Miller asserts that Valley Restaurant serves some of the finest Filipino cuisine in Juneau.

Miller asserts that Valley Restaurant serves some of the finest Filipino cuisine in Juneau.According to Miller, the best place to experience adobo reminiscent of Pelayo's and his mother's cooking is the Valley Restaurant in Juneau. 'They have the best food ever,' he remarks. 'Nothing compares.' The Valley, located just downwind of the Mendenhall Glacier and about a mile from the airport, is a cozy, low-profile red building resembling an old caboose. It’s filled with regulars seated in pleather booths, sipping from thick-walled coffee mugs. A wooden flounder hangs from the rafters, reminiscent of a household saint.

I visit the Valley with Marcelo Quinto and Bob Paulo, both respected Tlingit elders in the community. At 81 and 71 years old, respectively, the two share a comfortable camaraderie built over decades of friendship. They’re well-known around town; the restaurant manager inquires why Paulo hasn’t been in recently, and a couple stops by to congratulate Quinto on selling his boat at last.

We settle into one of the booths and place our order for chicken and pork adobo. Following a refreshing house salad, the adobo is served in almond-shaped gratin dishes. The sauce glistens like polished mahogany, where sugar and soy have melded into a rich, molasses-like sweetness. Whole spices float within: a coriander seed here, a clove there. The flavor profile evokes Christmas — figgy pudding, mulled wine — rather than the tart, garlicky adobo my grandmother used to prepare.

Bob Paulo, an elder of the Douglas Indian Association in Juneau, identifies as Tlingit-Filipino and remarks that in his community, 'everyone cooks.'

Bob Paulo, an elder of the Douglas Indian Association in Juneau, identifies as Tlingit-Filipino and remarks that in his community, 'everyone cooks.'The two men share laughter as they reminisce about their childhoods, but it's evident that growing up mixed-race in the early 20th century posed challenges. Quinto and Paulo belong to a generation that identifies as mestizo or 'Tlingi-pino.' Their fathers were Alaskeros, while their mothers were Tlingit women who worked beside them in the canneries. 'My mother always told me, you're Filipino and you're Tlingit, and never forget it,' recalls Quinto. His mother, Bessie Quinto (née Jackson), played a significant role in forming Juneau's Filipino Community, Inc. with other Tlingit wives to create a social space for their families in a segregated city. This organization still thrives today, with a community hall in downtown Juneau.

Quinto reminisces about cooking adobo in the cannery, where they browned meat and created a dark gravy from the drippings — soy sauce wasn’t available in U.S. stores until the 1970s. Garlic, onion, and vinegar were used to mimic the familiar flavors of home. (In 1977, Pelayo's wife Kaa T’eix published a Tlingit cookbook featuring a seal adobo recipe that employed a similar technique, adding paprika and Accent-brand MSG for extra umami.)

The discarded parts from the canneries — heads, spines, fins, and other remnants — became a vital food source for the camps. Tlingit workers transformed the heads into k’ínk’, also known as stinkheads, a delicacy with an aroma reminiscent of washed-rind cheese. Meanwhile, Filipinos utilized the fins, spines, and intestines to create their own fermented fish product: bagoong, a key condiment typically made with krill or small fish in the Philippines. Over time, each group grew fond of the other's fermentation techniques. Miller recalls tales of his grandmother sneaking off with her Filipino friends to Todd Cannery’s smokehouse to share stinkheads and chat. 'They'd laugh and giggle so much that you could hear them all through the camp,' he reminisces.

Although initially hired as seasonal laborers, many Alaskeros decided to settle permanently in Alaska and entered the food industry. By the 1940s, well before Anthony Bourdain forecast that Filipino cuisine would be America’s next big trend, Filipino restaurants had already become common in Southeast. In Ketchikan, the DeLuxe Cafe was run by C. Mendoza and Victor Ortaliza, while Tenakee Springs had H.J. Floresca’s Blue Moon Cafe & Bakery. The Pelayos operated at least five restaurants in Sitka and Juneau. These establishments offered Filipino dishes — or the best approximations in an era lacking Asian supermarkets and imported bagoong — while also serving as community gathering spots for breakfast staples like bacon and eggs, steaks, and local gossip.

Besides adobo, Marcelo Quinto prepared fish head soup for a recent mestizo picnic that also served as a memorial for his wife, who passed away earlier in the spring.

Besides adobo, Marcelo Quinto prepared fish head soup for a recent mestizo picnic that also served as a memorial for his wife, who passed away earlier in the spring. A girl presents Filipino fry bread at the picnic memorial.

A girl presents Filipino fry bread at the picnic memorial.Other Filipino chefs gained recognition for their work in local hotels and aboard the Alaska Marine Highway, the state-operated ferry system known for its once-elegant dining reminiscent of classic ocean liners. One notable executive chef from the Marine Highway, Andres Aquino Cadiente, released a cookbook in 1974 titled “El Mundo Food Almanac,” featuring a foreword by former Alaska governor William Egan. Among its recipes is “Chicken Adobo ala McArthur” (named after Arthur MacArthur, the third military governor of the Philippines), which, like Kaa T’eix’s seal recipe, includes MSG, paprika, but no soy sauce. Cadiente noted that Filipino cuisine had already become part of Alaska’s dining landscape: “Many of the Filipino dishes of today have become a welcome variation to western cookery,” he stated.

Quinto also worked in the kitchens of the Marine Highway and at Juneau’s Baranof Hotel, a major employer of Filipinos where his father (also named Marcelo Quinto) served as a bartender for 30 years. Later, the younger Quinto applied his culinary skills at the Alaska Native Brotherhood, an organization he has been part of since 1951; he was elected Grand President last November after over 15 years leading the Glacier Valley camp. Under his guidance, Glacier Valley generated funds by catering corporate events for clients like Sealaska and Goldbelt. Adobo became a staple at these Native gatherings.

The next generation of Southeast adobo

Quinto took me to Gajaa Hít, home to a carving workshop run by the Sealaska Heritage Institute, to introduce me to his protégé, Donald Gregory, also known as Héendeí. Officially, Gregory is the facilities and special projects coordinator at Sealaska Heritage, a nonprofit dedicated to promoting Tlingit, Tsimshian, and Haida art and culture, but he also works as Quinto’s sous chef. He paused from carving an eagle mask to discuss Filipino cuisine with me.

George and Marcelo Quinto, brothers and first-generation Tlingit-Filipino residents of Juneau.

George and Marcelo Quinto, brothers and first-generation Tlingit-Filipino residents of Juneau.Gregory began working with Quinto at the age of 18, mastering the vibrant flavors reminiscent of his Filipino grandfather’s kitchen. During his first job, Quinto reprimanded him for cutting the meat for adobo too large, insisting, 'Hey, we’re cooking for Goldbelt, cut that four more times!' Events often drew more guests than anticipated.

His adobo base for large batches consists of equal parts vinegar and soy sauce, plus double the amount of water; spices are placed in a large tea ball that floats in the enormous pot. 'It’s kind of mellowed out, and it doesn’t have the real strong taste to it,' he explains. 'But when cooking for hundreds, there’s no time for marinating. It’s going in the pot and it’s getting turned on.' In his free time, Gregory enjoys crafting what he calls 'Tlingit soul food,' particularly his smoked seal ribs simmered with aromatic ingredients.

Like many Alaskeros who married Tlingit women, Gregory’s grandfather worked hard to blend into his wife’s culture. He was adopted into the Brown Bear clan, mastered the complex language, and became one of the clan’s finest fishermen. Though he’s technically Gregory’s step-grandfather, Gregory recalls, 'Growing up, I never knew he wasn’t my mom’s real dad.' One day, when he was 18, he told someone he was a quarter Filipino, and his mother later corrected him, saying, 'You know, you’re not Filipino.' He burst into tears, questioning why she had never revealed the truth.

Two generations removed from the Alaskeros, Gregory represents how Filipino cuisine and identity intertwined with the local Southeast culture. He grew up on South Franklin Street, the once “rough downtown” of Juneau, where discriminatory housing policies confined non-white residents. 'Many Filipinos and Tlingits lived there, and the Filipino Community center was just across from my apartment,' he recalls. He fondly remembers neighborhood kids gathering at the community hall to watch TV and play pool before fishing under the dock or having BB gun battles. 'Some kids were Tlingit, some mestizo, and the rest were full Filipino; we were all like brothers,' he shares.

Juneau resident Kendri Cesar proudly displays her heritage with her dad's T-shirt. Many people in the community identify as mestizo or 'Tlingi-pino.'

Juneau resident Kendri Cesar proudly displays her heritage with her dad's T-shirt. Many people in the community identify as mestizo or 'Tlingi-pino.' Ricky Worl, 23, barbecues ribs at the recent mestizo picnic, proudly carrying the middle name Marcelo in honor of Marcelo Quinto.

Ricky Worl, 23, barbecues ribs at the recent mestizo picnic, proudly carrying the middle name Marcelo in honor of Marcelo Quinto.Raymond Gregory, known as Took, carries the name of his Filipino great-grandfather. A Tlingit artist skilled in carving, singing, and dancing, the younger Gregory travels worldwide to share his craft and studied sculpture at the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe. He also passes on his family’s pork adobo recipe, featuring pickling spice and apple cider vinegar, to those he meets in his travels. 'But it’s nowhere near as good as my uncle’s,' he admits.

Raymond Gregory represents a new wave of Alaska Native youth dedicated to promoting and enriching their cultural heritage, grounded in traditional histories and values. Food plays a crucial role in this mission: he takes pride in his understanding of traditional halibut drying techniques and hopes to learn about harvesting kóox, or chocolate lily, a wildflower whose bulbs can be eaten like rice. Yet, adobo will always have a place on the table. 'Most Natives know how to make adobo, and many families prepare Filipino dishes,' he states. 'We’re huge adobo fans. We just adore it, it’s that good.'

Young Filipino chefs in Juneau are continuing this culinary legacy. Rachel Barril, the chef de cuisine at In Bocca al Lupo in downtown Juneau (whose chef, Beau Schooler, was a James Beard Awards semifinalist for Best Chef: Northwest in 2019, 2020, and 2022), has Alaskeros in her family tree on both sides, and the current owners of the Valley Restaurant are her relatives. She experiments with Filipino-Alaskan fusion dishes on In Bocca al Lupo’s specials board, such as kare kare featuring foraged mushrooms and beach greens, and crispy king salmon collars dressed in a sweet-and-sour escabeche sauce. 'Growing up American, embracing Filipino culture, and being Alaskan surrounded by abundant natural resources — that’s essentially what my specials reflect,' she explains.

A display of skewered pork belly at Carillo’s, the Filipino food truck.

A display of skewered pork belly at Carillo’s, the Filipino food truck.At the Rookery Cafe, the sister restaurant of In Bocca al Lupo, there's an adobo loco moco that Barril added to the permanent menu during her time there. A layer of caramelized onions crowns the hamburger patty, with the egg edges delicately fried into a lacy frill. The adobo sauce that cascades over the glacial mound of rice might first remind you of demi-glace, but a taste reveals a closer relationship. Subtly sweet and spiced with pepper, it’s just thick enough to cling to the back of a spoon, reminiscent of the adobo served at the Valley Restaurant or in the homes of the Miller and Gregory families.

Is this adobo truly authentic, or simply Filipino? 'To be fully authentic, I'd need to travel to the Philippines, grow my own rice, and raise my own chickens,' Barril explains, noting that she doesn't view the adobo loco moco as authentic in the traditional sense. 'However, it reflects many influences from my life and what’s accessible here. That’s what makes it authentically mine.'

Jennifer Fergesen is a writer, editor, and the author of The Global Carinderia, which delves into the Filipino diaspora through the lens of food.Ash Adams is a photojournalist and editor based in Alaska, California, and New York. Copy edited by Paola Banchero

1

2

3

4

5

Evaluation :

5/5