Discovering Community (and Pancit Canton) in America’s Oldest Resort Town

Wolfeboro, New Hampshire, features sidewalks adorned with a colorful mix of melted ice cream. Its shimmering lakes, once home to grand hotels, now host expansive vacation homes. This picturesque setting earns Wolfeboro its title as the 'oldest summer resort in America,' rooted in the history of Governor John Wentworth, who built a lakeside estate in 1768 before being ousted by 'rambunctious patriots' six years later. This charming narrative draws visitors, though it often overlooks the Indigenous Abenaki people who lived on this land long before, suffering from the violence and diseases brought by colonial expansion. Each summer, Wolfeboro’s population swells with tourists and celebrities like Mitt Romney, Jimmy Fallon, and Drew Barrymore.

While the local cuisine mostly offers standard American dishes, just a few miles from town lies a hidden gem. East of Suez, one of America’s oldest pan-Asian restaurants, occupies a humble, century-old building that was once the dining hall of Camp Wunnishaunta, an informal Jewish day camp for adults, and later a pizza restaurant.

In 1967, Charlie and Norma Powell, New York City residents, bought this building on a whim. Norma had recently immigrated from the Philippines to work at the Philippine Consulate, and her friend, Tarcela Cabunilas (affectionately known as Mama Tars), had moved to the U.S. to help care for the Powells’ home and daughters. Charlie, a white Manhattan advertising executive, had traveled extensively throughout Asia with his father, a naval officer and photojournalist.

The trio often spent summers in a family cottage nearby that had been in Charlie’s family since the late 1800s. However, they lamented the absence of Asian cuisine in the Lakes Region and decided to open their own restaurant to fill that gap.

The Powell family on their opening day during the 1960s.

The Powell family on their opening day during the 1960s.During its inaugural summer, East of Suez operated for just one weekend. The next summer, it opened for a week, then reverted to weekends only. Eventually, the restaurant welcomed guests every July and August. Over time, it gained popularity, offering Korean bulgogi, Philippine adobo, pad thai, and Japanese tempura, serving up to 40 patrons each night. Weekly, the Powells would load a turquoise VW Beetle with essentials like rice, oyster sauce, gallons of soy sauce, sesame oil, fresh noodles, daikon root, napa cabbage, bean sprouts, snow peas, and shiitake mushrooms from New York's Chinatown before making the 300-mile journey to Wolfeboro. Now celebrating its 55th season, East of Suez operates roughly from Memorial Day through Labor Day. When the sign goes up at the start of the season, locals recognize it as a herald of summer's arrival.

Situated just outside the bustling downtown area, East of Suez caters to a select group of the 6,547 residents who call Wolfeboro home year-round, offering a slice of familiarity to Asian American and Pacific Islander communities from across New England. Over its five-decade history, the restaurant has hosted countless significant events: reunions, fundraising dinners for local causes, bridal showers, weddings, and memorial services. The Powells’ daughters, Elizabeth (Liz) Powell Gorai and Charlene Powell, grew up amidst the restaurant's hustle, often seen lounging in beach chairs near a small black and white television tucked away in the kitchen. Charlie often remarked that Liz was peeling garlic by the age of five.

Liz has been the primary operator of the restaurant for many years. Norma tragically passed away in 1978 due to a car accident, followed by Charlie in 2001 after a brief illness, and Mama Tars in 2021. Each loss has posed a challenge for East of Suez, but the family and community have consistently come together to keep the restaurant thriving, recognizing the unique legacy it holds. The current staff comprises a mix of locals, the Powells' relatives, and extended family from the Philippine diaspora, including some who travel every summer just to work there. 'The parking lot may reflect small-town New Hampshire,' a former staff member remarks, 'but once you step inside, you’re transported to another world.'

Shrimp and vegetable tempura.

Shrimp and vegetable tempura. Philippine adobo

Philippine adoboAt 15, I began working for Charlie in 1997, just back from boarding school. Despite my family being white, like 95 percent of Wolfeboro’s residents, I never truly felt at home there. My father was a merchant mariner, and my mother hailed from London; their move to Wolfeboro felt somewhat arbitrary. I kept my English accent until second grade, learning that if I pronounced 'vitamin' differently, I could avoid teasing. Yet, the pressure to fit into Wolfeboro’s seemingly uniform preppy culture didn’t resonate with me. I left for school as soon as possible, only returning during the summer, blending in with the seasonal tourists. I was unfamiliar with the cuisine East of Suez offered and lacked any waiting experience, but for the first time in Wolfeboro, I found a sense of community grounded in mutual respect.

Dining at East of Suez has never been fast-paced, but it's always filled with warmth. One patron recalls that after requesting tofu during a meal in the early '90s, Charlie sent someone out to fetch it. He was the epitome of hospitality, often frying crispy shrimp tempura for guests waiting for a table or emerging from the kitchen with a bottle of sake or plum wine to share with lingering diners. On some evenings, he would even join guests at the piano for a sing-along. A list of rules on the fridge stated: “No. 1: The customer is always right. No. 2: If the customer is wrong, refer to rule No. 1” — though if a customer was particularly rude, Charlie would step out to say, “Tonight, dinner is on me. But please don’t come back.”

He extended the same generosity to his staff. Occasionally, I'd call Charlie during the day to ask if I could skip work to catch a movie with friends. “That’s perfectly fine,” he’d reply, “We’ll just take fewer reservations.”

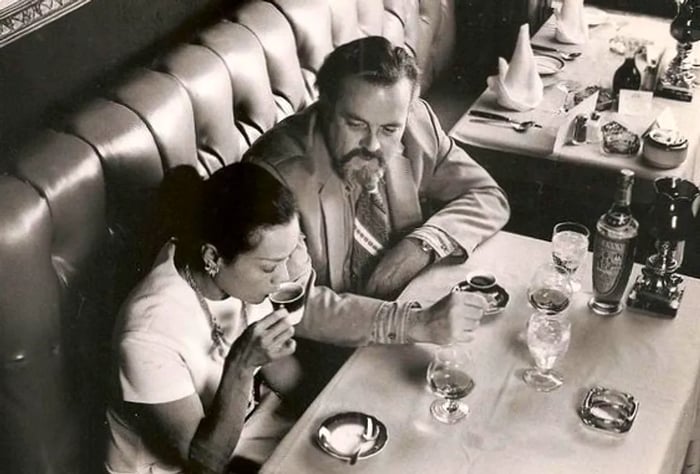

Norma and Charlie in 1962.

Norma and Charlie in 1962.After her father's passing, Liz, then 38, was living in Manhattan with her two young children and husband, Katsu, with whom she operated a karate school while also caring for Katsu's ailing father back in Japan. Her sister, Charlene, resided on the West Coast, and Mama Tars had relocated to Texas in the '70s. Despite feeling overwhelmed by the prospect of running a restaurant, with encouragement from her aunt Alice and her older sister/friend Aida, she decided to take on the challenge.

Numerous family members returned to Wolfeboro to honor Charlie’s memory, lending a hand during that first summer without him. Particularly after the passing of Liz’s father-in-law and the events of September 11, the family concentrated on reuniting and reconnecting with their heritage. More cousins visited to help out. Mama Tars returned to work and cared for Liz’s children, becoming a beloved grandmother figure at the restaurant, gently reminding us not to take ourselves too seriously while serving us leche flan or rich sans rival once the customers had left.

The restaurant exudes the charm of a cherished patchwork. Its jade green walls, complemented by varnished wood accents, are filled with photographs, souvenirs, vintage movie posters from Charlie’s father’s days in Asia, and various knickknacks gifted by patrons. The mismatched dishes reflect the family’s affinity for yard sales. During my time under Charlie’s stewardship, there never seemed to be enough glasses, ice, corkscrews, or menus.

Some of the unique decorations — antique masks and other artifacts collected by the Powells, as well as a doll created by a customer resembling Charlie — have gone missing. At the entrance lies a large clam shell imported by Norma from the Philippines in the 1960s. While some staff believe there were six of these shells, Liz thinks there were three. Regardless, the missing shells were likely taken, as artifacts from the endangered species can command high prices. Last year, someone contacted Liz claiming to have found a “missing” shell in the woods, demanding $200 for its return, to which she replied to leave it where it was. Although Liz is saddened by the loss of these items, she believes that “for everything that goes out the door, even more comes back.” East of Suez maintains strong connections with Wolfeboro’s small business community, often bartering services, like free repairs for Charlie’s Beetle or a new ice maker in exchange.

Under Liz’s leadership, the restaurant has expanded, now serving 125 guests each night. She has collaborated with Aida, Alice, and various guest chefs to enhance the menu, adding more vegan, vegetarian, and gluten-free choices along with locally sourced ingredients. At the pandemic's onset, when core staff could not travel, Liz quickly trained her husband and children to cook, ensuring the restaurant remained open. Following George Floyd’s death, they displayed a Black Lives Matter sign in the window. Although they faced some backlash on social media, the sign remained. “People of all political backgrounds dine here, as long as they’re willing to share great meals with others. I hope the spirit of this place extends to people’s homes,” Liz shares. “Hospitality goes beyond serving; it’s about how we treat one another.” In 2020, they updated the fridge rules to say: “No. 1: have fun, No. 2: smile, and No. 3: make it sarap (delicious in Tagalog).”

The East of Suez sign.

The East of Suez sign. Spicy tuna served on crispy rice.

Spicy tuna served on crispy rice.The family has thought about launching a branch of the restaurant in downtown Wolfeboro, the vibrant Portsmouth, Manhattan (where Liz runs a pop-up pan-Asian cafeteria called Mama T. NYC, a tribute to Mama Tars), or even in the Philippines. Yet, despite its seemingly outdated surroundings, Wolfeboro has been the perfect setting for East of Suez to flourish.

Ninety percent of independent restaurants shut down within their first year, and those that survive typically last an average of five years. Against all odds, East of Suez has thrived for over fifty years. Wolfeboro attracts visitors — including myself. Although my family no longer resides there, I’ve established a tradition of enjoying an annual meal at the restaurant with my children, who have formed connections with Liz, Aida, and the rest of the team. For the Powells, Wolfeboro has been a source of summertime solace for more than a century, and at East of Suez, they extend that warmth to every guest who walks through the door.

Michele Christle is a freelance writer focused on culture, ecology, and community. Her articles have appeared in Down East, Maine Homes by Down East, and The Kenyon Review. In addition to her writing, she works in nonprofit communications and resides on unceded Wabanaki territory in midcoast Maine.

1

2

3

4

5

Evaluation :

5/5