Emerging Bakeries Are Gaining Popularity in Puerto Rico

Pan sobao, with its soft and doughy texture, is a staple throughout Puerto Rico. This beloved sweet bread can be found in nearly every bakery, supermarket, and even at some gas stations, often in heated display cases. Locals enjoy it in various ways: toasted, as sandwiches, or even as a simple slice used to soak up drippings from chicken pinchos. It holds a place in Puerto Rican culture akin to lechón asado, mofongo, or pasteles.

Pan sobao is not just iconic due to its widespread presence and deep ties to the island's Spanish baking heritage; it also symbolizes the shortcomings of Puerto Rico's industrial baking system.

“Today's typical pan sobao is made from enriched, bleached flour blended with vegetable shortening, loads of sugar, and numerous leavening agents to ensure quick rising. It’s often underbaked, resulting in that signature doughy texture,” explains Diego San Miguel, who launched Panoteca San Miguel in 2021 in San Juan's Río Piedras area. “Many enjoy it, yet no one questions the process. Nobody thinks, ‘This isn’t made correctly.’”

In 2016, San Miguel began crafting bread using a second-hand pizza oven in a modest ghost kitchen in Cupey, becoming part of a new wave of Puerto Rican bakers offering alternatives to mass-produced breads: sourdoughs, artisanal country loaves, and pastries filled with fresh creams and local fruits. While this may appear to be a late embrace of baking trends from the U.S., Puerto Rican bakers encounter distinct challenges in sourcing ingredients and overcoming cultural stigmas—yet they are also creating new baking traditions that reflect the island's culinary heritage.

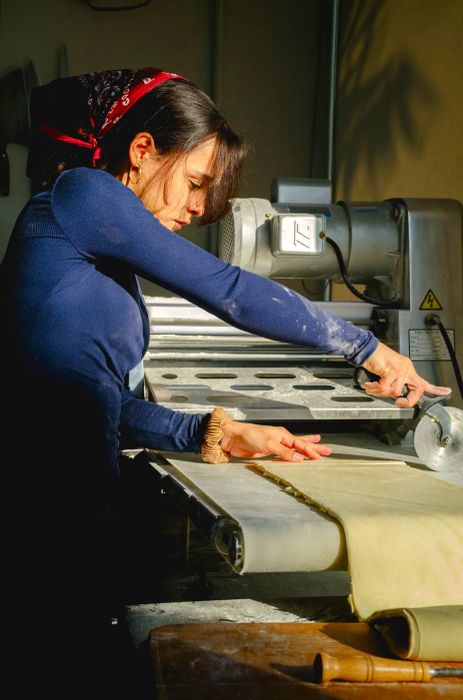

Head pastry chef Lauren Collazo skillfully handles croissant dough at Panoteca San Miguel.

Joseph Lopez Hidalgo

Head pastry chef Lauren Collazo skillfully handles croissant dough at Panoteca San Miguel.

Joseph Lopez Hidalgo Diego San Miguel diligently at work.

Joseph Lopez Hidalgo

Diego San Miguel diligently at work.

Joseph Lopez HidalgoWheat was introduced to Puerto Rico by Spanish colonizers in the early 16th century. As time passed, Spanish bakers established themselves on the island, constructing brick ovens to bake various breads and sweet buns from different Spanish regions. Today, a few panaderías still utilize these original brick ovens, and it's typical to find a bakery in every town square offering variations of criollo bread (pan de agua), treats like quesitos, and of course, pan sobao.

During the industrialization of food production in the 1940s and ’50s, Puerto Ricans began to consume more processed foods, aligning with trends in the U.S. Bread-making transformed into a factory-driven process that overlooked the importance of quality ingredients and fermentation. Pastries were created using pre-made mixes and creams. Bakeries modified traditional recipes in the name of health, often making matters worse; by the 1970s, pork lard, an essential component of pan sobao, was deemed unhealthy and replaced with hydrogenated vegetable shortening, devoid of nutritional benefits. Consequently, Puerto Ricans became accustomed to bland tornillos filled with dense pastry cream and breads that remained soft for extended periods.

A selection of croissants, country scones, and financiers displayed at El Horno de Pane.

Rafael Ruiz Mederos

A selection of croissants, country scones, and financiers displayed at El Horno de Pane.

Rafael Ruiz MederosThe emerging movement to challenge these practices began with María Isabel Laborde. In 2000, she traveled to the Dominican Republic to train as a baker; upon her return, she discovered her breads were not the same due to the incorporation of additives like potassium bromate in locally milled flour. This chemical compound is a recognized carcinogen, linked to gastrointestinal problems, and banned in many countries, yet it remains in use in the U.S. and Puerto Rico to enhance dough. She began advocating against such chemical additives and began selling sourdough bread made with organic flour.

More bakers joined her cause, but it has been a challenging journey. While Puerto Ricans cherish their bread, many have shown little interest in the baking process. Lawyer-turned-baker Carlos Ruiz notes that when he opened El Horno de Pane in the Hato Rey district of San Juan in 2016, many customers favored convenience over quality.

“Customers would come in at 3 p.m. and exclaim, ‘Oh, you don’t have anything left!’ because they’re used to bakeries with fully stocked displays,” he recalls. “Some would even get angry and insult me, saying, ‘You don’t know what you’re doing! How is it possible that there’s nothing left at this hour?’ But everything is made fresh every day, from scratch.”

“In Puerto Rico, when you tell someone you’re a bread baker, they often look down on you,” explains San Miguel, who began his journey at Panadería Morales in Gurabo, where he experienced an industrial approach to baking. It was only after a year in France that he encountered skilled bakers who took great pride in their craft.

Trimming the edges of quiche lorraine at Levain Artisan Breads.

Rafael Ruiz Mederos

Trimming the edges of quiche lorraine at Levain Artisan Breads.

Rafael Ruiz MederosPursuing training outside of Puerto Rico has been essential for many of the island’s top contemporary bakers, including Ruiz and José Rodriguez, who founded Levain Artisan Breads in 2009 after completing the bread program at the International Culinary Center in New York. He has since opened bakeries in Aguadilla and Santurce while also participating in baking workshops around the world.

These international experiences have shaped the offerings of bakers. San Miguel experiments with light Italian maritozzi, Rodriguez has gained recognition for his croissants, and Ruiz lists almond croissants and kouign amanns among his top sellers. The influence is particularly evident for Lucía Merino. As a young pastry cook in Miami, she trained with a master pastry chef who inspired her to pursue her passion for patisserie. After gaining experience in Spain and Dallas, she returned home to focus on her craft, including laminated dough and pâte à choux, at Lucía Patisserie, a bakery influenced by French techniques in the Miramar neighborhood of San Juan. (Note: Lucía Merino is the sister of Camila Merino, who has also worked at Lucía Patisserie.)

While bakers may dream of French boulangeries and Italian pasticcerias, they face challenges in sourcing ingredients in Puerto Rico. As a U.S. commonwealth, Puerto Rico imports over 80 percent of its food. The Marine Merchant Act of 1920, known as the Jones Act, requires that goods be transported to the island on U.S.-flagged ships, leading to significant price increases and supply limitations.

When Laborde began her journey to bake bread commercially, she struggled to convince a local Dawn Foods sales representative to bring King Arthur’s organic flours to the island.

“I think the lady didn’t take a liking to me from the start. She kept insisting that flour spoils quickly and is costly, claiming nobody would buy it,” Laborde recalls. “I offered to buy the entire pallet. Maybe she didn’t believe me.”

Laborde eventually hired a courier from Florida to deliver King Arthur flour from North Carolina. This made the premium ingredient even pricier, but it set the stage for Rodriguez, who persuaded the same representative to import King Arthur flour a few years later. (This flour was essential for the sourdough pizza shops that emerged across the capital, confirming Laborde’s predictions about demand.)

Jose Rodriguez scores sourdough loaves at Levain Artisan Breads.

Rafael Ruiz Mederos

Jose Rodriguez scores sourdough loaves at Levain Artisan Breads.

Rafael Ruiz MederosHowever, even modest successes haven't eased concerns. Following Russia's invasion of Ukraine, wheat prices soared, and bakers observed a decline in quality. At one point, Ruiz paid $290 to ship a $100 bag of flour to Puerto Rico. The same unbromated flour that initiated Puerto Rico’s neo-baking movement has also become increasingly difficult to obtain; shipments may be delayed or sell out rapidly.

Other ingredients are just as tricky to manage. On several occasions, Ruiz has found himself with only one box of European butter left, joking anxiously that he was “on the verge of hitting the panic button.” Merino faces similar challenges sourcing ingredients like nuts and chocolate, as her delicate pastries are particularly sensitive to unexpected supply disruptions.

“We organize our weekly menu and order the ingredients we need for production, but sometimes certain items don't arrive, or the quality falls short,” she explains. “It can be incredibly stressful.”

The challenges have prompted bakers to innovate. When Rodriguez struggled to find European-style butter, he tried to replicate it by processing local butter to decrease its water content and boost its fat percentage. Ultimately, he opted for butter directly imported from France via New Jersey due to the inconsistency of his homemade attempt.

The team at Lucía Patisserie had better luck when they made their own hazelnut praline after struggling to find it. They also choose to create their own versions of pricey ingredients like vanilla extract.

While bakers often lament their limited access to European ingredients, they have also learned to appreciate the abundance available locally. Although local eggs tend to be more expensive than imported ones, a single local egg can equal 1.5 to 2 U.S. eggs, and bakers favor their superior quality. Panoteca San Miguel highlights local fruits such as pomarrosa and passionfruit in their pastries. When a generous neighbor in Aguadilla donated his entire harvest of fresh guayabas, the Levain team turned it into jam, pairing it with local queso fresco for a danish that quickly sold out.

“Every pastry we create using fresh local fruit is a hit,” says Merino. She collaborates with farmers to source limes, ginger, hibiscus, and watermelon for juices; herbs, eggplant, and squash for savory galettes; passionfruit for macarons; mango for tarts; and more. For Thanksgiving, Lucía Patisserie processed over 400 pounds of local pumpkins for their pies.

“We must demonstrate to farmers that there is demand for their products and that we are willing to pay a fair price if we want to change our island’s dependency on imports,” she emphasizes.

Passion fruit and dark chocolate tart from Lucía Patisserie.

Johan Villafañe Lopez

Passion fruit and dark chocolate tart from Lucía Patisserie.

Johan Villafañe Lopez Galette de rois filled with hazelnut frangipane at Lucía Patisserie.

Johan Villafañe Lopez

Galette de rois filled with hazelnut frangipane at Lucía Patisserie.

Johan Villafañe LopezThe European techniques and pastries that inspire bakers can also alienate some customers, who might initially feel overwhelmed by unfamiliar items, Rodriguez notes. Thus, blending in familiar flavors has been essential to winning over hesitant locals.

“Our customers are drawn to pastries that evoke traditional Puerto Rican flavors,” says Merino. In addition to incorporating local fruits, she offers a Croixito, a croissant-inspired pastry reminiscent of quesito, and a beloved hand pie filled with picadillo and sweet plantain. Recently, she has been experimenting with crispy puff pastry to recreate classic items like napoleons and pastelillos.

Embracing Puerto Rican flavors is more than just good business; it's part of a broader initiative to foster a local, self-sustaining baking culture that celebrates Puerto Rican traditions. “Puerto Rican breads have been unfairly labeled as inferior to European varieties, but that’s not the case. The real issue lies in the methods and ingredients used,” explains San Miguel.

While pioneering bakers once had to journey around the globe to hone their skills, they aim to change that for future generations, ensuring that education is accessible to all, not just those who can study abroad. Rodriguez has been conducting baking workshops across Puerto Rico, and both he and Laborde are exploring the idea of establishing permanent baking schools.

“People rely on these breads now,” says Laborde, who often sells out her loaves at her restaurant, Peace n Loaf, in her hometown of Cayey. “That’s why we need more bakers.”

Their dedication is yielding results. Bakeries appreciate that their craft has gained popularity among a growing local audience, as well as Puerto Ricans abroad and international visitors. Meanwhile, a new wave of bakers is launching creative micro-bakeries, such as Mugi Pan, which draws inspiration from both Japanese and French techniques.

San Miguel successfully brought back the much-maligned pan sobao using local organic lard, eggs, and honey.

“It was amazing. It tasted exactly like the pan sobao we remember,” he remarks, “but it was made properly.”

Camila Merino is a freelance writer based in San Juan, Puerto Rico, with nearly a decade of experience in food and service.

Local pumpkin danish at Lucía Patisserie.

Johan Villafañe Lopez

Local pumpkin danish at Lucía Patisserie.

Johan Villafañe Lopez

1

2

3

4

5

Evaluation :

5/5