Forget Night Markets—Here’s Why Rechao Restaurants Are Taiwan's Must-Visit Spots

I've been dining at Taiwanese rechao restaurants for as long as I can remember. My earliest Taipei memories involve sitting outdoors at small tables with my parents, enjoying dishes like wok-fried eggplant and poached calamari drizzled with sweet and sour chili sauce. Specific moments linger: the vivid vermilion of the tables against soft-pink plastic chairs, the flickering light of a broken streetlamp nearby, my dad's beer bottle sweating in the heat, and the constant hum of passing motorcycles. As a child visiting Taiwan from the U.S., I found rechao to be a whirlwind. However, after relocating to Taipei at 29, these restaurants became my refuge—places to gather with friends amidst the familiar, comforting sounds of the island.

In Mandarin, rechao means “hot stir-fry” and denotes a type of late-night eatery—often featuring low outdoor seating right by the street—that serves Taiwanese favorites like three-cup chicken, hearty fried rice, and garlic-infused stir-fried clams. Unlike night markets—bustling markets that come alive after dark—rechao restaurants are a unique entity in themselves. They're present in nearly every major neighborhood across the island but are especially prevalent in northern Taiwan.

Dishes at rechao are nearly always cooked over intense heat—tossed and flipped in large woks. A powerful stove is essential, ensuring that rechao meals come out quickly, a rapid succession of hot plates. The speed of preparation is a hallmark of the experience, and the food—savory with rich umami layers—is crafted to complement beer. Yet, rechao represents more than just dining; it's a cultural experience.

Photo by An Rong Xu

Crucially, the rechao menu weaves a rich narrative about what it means to be Taiwanese, reflecting a multicultural and intricate identity. These restaurants aren't just about singular dishes; they're versatile establishments designed to satisfy a wide audience. The cuisine is straightforward and quick, showcasing the island's bounty of crops, seafood, and proteins. As Kuo Chung-Hao, a food history professor at Taipei Medical University, puts it: “Rechao food is the food of the people.”

For my friends and me, it’s also an opportunity to throw a big gathering. Whenever a returnee, visitor, or newcomer arrives, one of us will arrange a rechao welcome dinner.

“Rechao, Friday at 7 p.m.?” I'll post on LINE, Taiwan's preferred messaging app, sending out the invitation to a diverse group of friends and acquaintances. By the week’s end, a dozen of us will gather around several long tables. Bathed in the soft light of yellow paper lanterns hanging above, we'll enjoy the evening as enthusiastic diners, savoring spicy braised stinky tofu and clay pot chicken simmered with the classic trio of soy sauce, rice wine, and sesame oil. As the night unfolds, the volume at the table rises, contrasting sharply with the reserved politeness that usually characterizes Taiwanese society during the day.

Photo by An Rong Xu

As a writer focusing on Taiwanese food culture, I find it challenging to fully convey the significance of rechao without comparing it to other culinary traditions. Much like Japanese izakaya and British pubs, rechao serves as a social hub where people gather to enjoy drinks. To me, it represents something fundamental and essential.

Regrettably, the culinary offerings of rechao are often overlooked within the broader narrative of the island's cuisine. Over the past year and a half, I've researched Taiwanese food extensively for a cookbook I'm writing, exploring various facets of the cuisine. I found that Taiwan is often stereotyped as a destination solely for night market treats or bowls of beef noodle soup, with rechao rarely receiving more than a fleeting mention.

Part of this oversight is geographic. While rechao is widespread throughout Taiwan, it hasn't gained significant traction internationally. The last major emigration wave occurred in the 1980s, just as rechao was starting to emerge, leaving it largely unknown to much of the Taiwanese diaspora (with a few exceptions). This lack of visibility is understandable: Taiwanese cuisine is seldom highlighted, and when it is, it often receives only a cursory glance, lumped into the broader category of Chinese cuisine.

Lettering by Jocelyn Chung

To grasp the importance of rechao, one must delve into Taiwan's complex history. Nestled by the Pacific Ocean, the nation's culinary landscape has evolved through centuries of colonial influences. Initially inhabited by Austronesian peoples, Taiwan saw the arrival of Chinese and Dutch settlers, who came to fish and cultivate the land. As immigration increased, the Austronesians were gradually outnumbered by the Chinese, and by the early 19th century, parts of the island were designated as a province of China under the Qing dynasty. The late 19th century brought Japanese rule, and in 1945, Taiwan was transferred to the Nationalist Chinese government—exiled to Taipei after a lengthy civil conflict with the Communists in China.

The 1980s marked another turning point when Taiwan embraced democracy. This newfound freedom fostered a unique Taiwanese identity distinct from China and Japan. About a decade later, the first rechao restaurants began to emerge on the island.

Photo by An Rong Xu

“The rechao phenomenon really surged in the 1990s, coinciding with Taiwan's economic boom,” Kuo explains. “After a long day at work, people wanted to relax.”

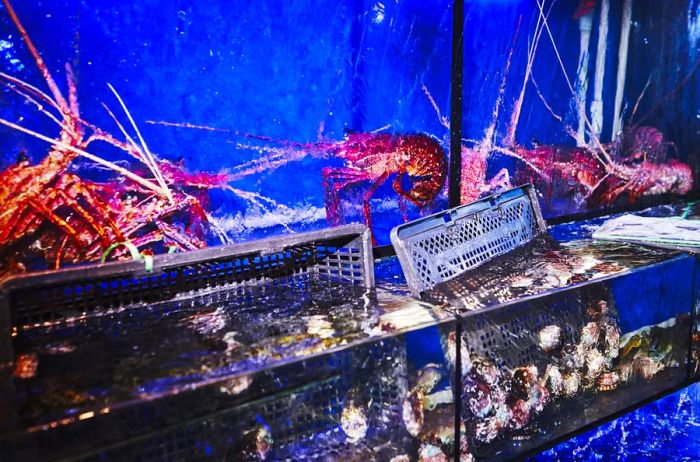

Street dining has been a staple of Taiwan's culinary landscape since the late 18th and early 19th centuries, when vendors strolled through bustling streets with buckets of food suspended from poles on their shoulders. These peddlers would gather around crowded Taoist temples, eventually laying the groundwork for Taiwan's night markets. Meanwhile, along the coast, seafood restaurants featuring live fish tanks began serving freshly caught fish, with chefs preparing whatever was available that day. According to Kuo, these seafood chefs gradually expanded their offerings, which eventually led to the establishment of rechao restaurants.

Some rechao venues still feature live fish tanks, allowing diners to select their preferred catch for the chef to prepare. In fact, some rechao owners permit customers to bring in their own catches, a practice embraced by Taiwanese food blogger He Chong-Yu and his friends on a regular basis: autumn is prime crab season, while winter is for cuttlefish. However, for most rechao establishments today, the menu has grown to include a diverse range of dishes beyond just seafood.

Photo by An Rong Xu

The rechao menu reflects the diverse cultural influences that have shaped the island over time. Japanese elements are evident in dishes like delicate sashimi paired with a dollop of tubed wasabi. Grilled salmon often comes glazed with a rich layer of miso. Other offerings, while not exact replicas of foreign foods, carry a distinctive Taiwanese twist. For instance, in Sichuan cuisine, poached pork belly is typically dressed with chili oil and light soy sauce, but in Taiwan, it’s coated in a diluted mixture of Taiwanese soy paste and ginger. Everything at a rechao has a touch more sweetness.

“Taiwanese cuisine stands apart from Chinese food,” states Chen I-Chin, the owner of Buzi Restaurant, a rechao spot in New Taipei City, located southwest of Taipei. Chen, who considers himself the “godfather of rechao,” claims to have been the first to bring this dining style into the spotlight in the 2000s. “We blended all eight major Chinese cuisines with Japanese influences to create something unique.”

As a result, rechao offers dishes that are truly one-of-a-kind, such as deep-fried shrimp tossed in sweet mayonnaise, pineapple, and a generous sprinkle of rainbow sprinkles, or a Hakka-style stir-fry featuring pork slivers, dried squid, tofu, and bright celery sticks. Indigenous Taiwanese ingredients also play a significant role: ferns, which flourish in Taiwan’s subtropical climate, are stir-fried with pickled birdlime seeds, small green olives that taste sweet like capers. Grilled pork sausages are occasionally infused with maqaw, an indigenous Taiwanese spice that has hints of pepper and lemon.

Photos by An Rong Xu

Although a menu with 100 to 200 dishes may seem overwhelming to a chef, the restaurant owners I spoke to insisted that it’s quite manageable. “Cooks only need to master the fundamentals,” says Hu Nei-Ta, co-owner of Fat Man Eatery, a rechao establishment in Taipei. “They should be proficient in cooking vegetables, fried rice, and noodles, as well as frying, grilling, and preparing cold dishes. Once they have that down, creating over 100 different dishes is straightforward.”

Beer plays a vital role in the dining experience. Taiwan has been brewing beer since the Japanese colonial period, but its popularity surged in the late 1980s and early 1990s with the influx of foreign brands like Heineken. Nowadays, rechao restaurants account for nearly 45 percent of all beer sales in Taiwan.

Affordability is another hallmark of rechao dining. “I started pricing plates at 100 NTD (about US$3), and the crowds were remarkable back then,” recounts Chen from Buzi Restaurant, which has been in operation for over two decades. Large blue signs still boast these prices, but in reality, only a handful of dishes cost that much today. “Food costs have risen significantly,” he explains. “Rice and ingredients were much cheaper in the past.”

Even so, dining remains relatively inexpensive. Based on my experience, the average bill per person is about US$15. While this is notably higher than a typical meal in Taipei, the key difference is that rechao represents a unique social experience, allowing people to linger for hours eating and drinking in the same place.

Photo by An Rong Xu

Nevertheless, dining at a rechao can be a bit cramped; patrons often find themselves seated closely together on low stools, all while the ever-present humidity of Taiwan envelops them. Yet, for devoted fans of rechao, the array of dishes is just as delicious as what one might find in any upscale restaurant in Taipei.

“I view it as a feast,” shares Acer Wang, a Taiwanese engineer residing in San Francisco. For him, the rechao restaurant is a cherished setting—a place where he and his friends can order without needing to speak. “There’s an unspoken agreement: one plate per person. We pass around the menu, and each of us selects a dish we desire. It’s quite harmonious.”

Photos by An Rong Xu

Last September, as Taipei's weather turned cooler, I decided to throw another rechao gathering for a few new friends from Europe. The auntie who welcomed us said, “I haven’t seen you in a while,” and immediately began listing the dishes I was bound to order: three-cup chicken, beef and pepper stir-fry, deep-fried sweet and sour fish, tender fern shoots, white pepper–dusted baby corn, egg fried rice, stinky tofu, eggplant, and a platter of stir-fried Taiwanese cabbage. I agreed to all her recommendations and even added a few of my own.

The dishes arrived at a rapid pace, and as my friends and I enjoyed the meal, I didn’t need to guide anyone on how to eat or explain the dishes. In that moment, I understood that despite my efforts over the past year to analyze rechao and its role in Taiwanese cuisine, the truth is that the rechao restaurant conveys its message perfectly—hot, quick, and lively. Simply glorious.

Additional reporting by Xin-Yun Wu. Wei’s cookbook, Made in Taiwan: Recipes and Stories From the Island Nation, is set to release on September 19, 2023.

1

2

3

4

5

Evaluation :

5/5