From tiger testicles to legendary feasts: The real food of China's emperors inside the Forbidden City

The Forbidden City once stood as one of the most formidable centers of power on Earth. In 1420, while Europe was engulfed in the Hundred Years’ War and had yet to discover America, China’s Ming Dynasty emperor was settling into his grand palace at the heart of Beijing, securing his reign over an expanding empire.

Within the vast walls of the Forbidden City, China’s emperors were untouchable, shielded not only by miles of fortifications but also by the impenetrable secrecy surrounding their lives. The palace was called ‘Forbidden’ for a reason—few ordinary Chinese were ever allowed entry.

The last emperor was ousted in 1924. Over the years, as the world’s largest palace complex began to reveal its mysteries to outsiders, even the deepest corners of the Forbidden City were slowly brought into the light.

But one mystery still lingers: the food.

Even decades after the collapse of imperial China, despite ongoing efforts by historians to explore the nation's history, little is known about the meals served in one of the world’s wealthiest and most influential households—particularly in its early years. Most ancient records that could shed light on this topic remain sealed due to their delicate condition.

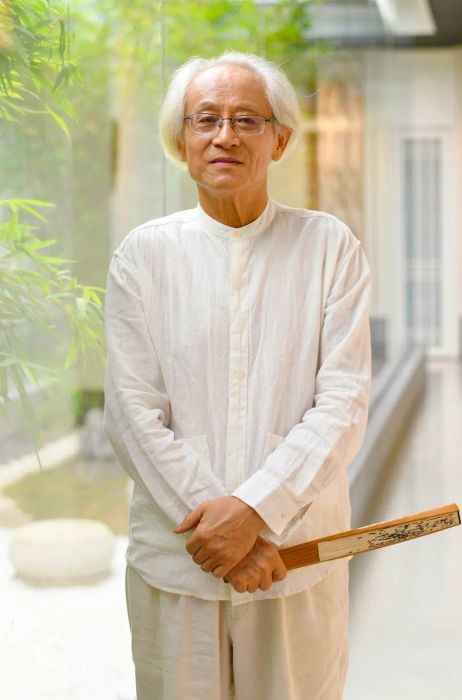

Zhao Rongguang, a food historian from Heilongjiang in northern China, stands as one of the few people—if not the only one—to have gained access to and thoroughly studied these ancient documents before they were locked away. His unique access allows him to challenge many long-held myths surrounding the Forbidden City’s cuisine.

Over forty years ago, Zhao embarked on a journey to uncover the Forbidden City’s culinary secrets.

Back in the 1980s, Beijing was still a city of bicycles and narrow alleyways—nothing like the sprawling metropolis of skyscrapers and highways it has become today.

But the 1980s were also a time of excitement, as China began to open up to the world once again after Deng Xiaoping’s “open door policy” was announced in late 1978. It was the decade when Wham! became the first Western pop group to perform in China since 1949, and when Paris’ famed Maxim’s restaurant opened its doors in Beijing.

Zhao, now 76, was undistracted by these new cultural waves. With money saved from his teaching job, he traveled to Beijing to pursue his goal of uncovering the true food history of China’s ancient emperors and their royal families.

It wasn’t an easy journey. Two main obstacles stood in his way. The first was the long-held secrecy surrounding the palace; for five centuries, little was known to the outside world about life within its towering red walls. The second was the fact that food wasn’t regarded as an academic subject in China, meaning documents detailing the meals of the early emperors were rare and scattered.

Undeterred, Zhao returned year after year to what was then known as the First Historical Archives of China, located at the old palace’s West Prosperity Gate (Xihuamen). There, he sifted through centuries-old imperial records, many of which he believes were locked away in the 1990s.

Gradually, Zhao pieced together the story of how dining traditions in the Forbidden City evolved, focusing on three key historical figures who significantly influenced royal eating customs. Nearly 40 years into his research, he now has a comprehensive understanding of the palace’s culinary history.

According to Zhao, the story begins with Kangxi, the emperor of the Manchu-led Qing Dynasty, who took full control of China after the fall of the Ming Dynasty in 1644, when the Han Chinese imperial family was overthrown.

During his reign from 1661 to 1722, China entered a period of relative peace after years of dynastic wars, leading to significant changes in the types of food served in the Forbidden City.

Initially, when the Qing Dynasty first settled in, traditional foods from the Manchu heartlands of northeastern China were served in the palace, based on historical records examined by Zhao.

During the middle years of Kangxi's reign, the royal cuisine began to undergo significant changes.

“Even then, Kangxi’s table still featured plenty of roast game and exotic dishes, like tiger testicles,” Zhao recalls.

Tiger testicles?

“Yes, tiger testicles. People in ancient times believed they had the power to boost libido. I believe Kangxi must have eaten quite a few, as official records show that he personally hunted over 60 tigers during his lifetime.”

Rooster combs were another aphrodisiac ingredient consumed at the palace, according to Zhao.

But as stability grew during Kangxi’s reign, more Han Chinese dishes began to make their way onto the palace menu, such as duck gizzard stew.

The Forbidden City’s golden influencer

The mysterious world of Forbidden City dining becomes clearer when we look at Kangxi’s grandson, the imposing Qianlong Emperor.

During his almost 61-year reign (1735-1796), which Zhao considers the second key phase in the evolution of Forbidden City cuisine, Qianlong had his daily menus carefully recorded, creating a paper trail that allows historians to paint a more accurate picture of palace life during his time.

For example, at the Hong Kong Palace Museum, an ongoing exhibition titled “From Dawn to Dusk: Life in the Forbidden City” is based largely on Qianlong Emperor’s daily routines, including his meals.

“What is the Forbidden City, really? It’s a city, an institution. Like any community, its food culture was a fundamental part of its identity,” says Daisy Yiyou Wang, deputy director of the Hong Kong Palace Museum, a sister institution to Beijing’s Palace Museum in the Forbidden City.

“The food culture itself is a mirror of the people’s identity: their status, power, authority, tastes, and relationships,” she adds.

Among the exhibits is a hefty silver milk teapot from the 18th or 19th century, placed beside a shimmering gold wine ewer adorned with cloud and dragon motifs, as well as a delicate glass bowl threaded with fine gold.

The intricately decorated teapot, with its gilded golden dragons, hints that milk tea, a staple of the Manchu diet, was a key element of the Qing Dynasty’s royal court meals.

“Tea bricks were broken into boiling water. Then milk, butter, and a pinch of salt were added. After filtering out the tea leaves, the tea was served in this type of silver teapot,” explains Nicole Chiang, the Hong Kong Palace Museum’s art historian and curator.

The salted milk tea serves as a reflection of the royal court’s Manchurian heritage.

“Even when Qianlong traveled to the Jiangnan region (south of the Yangtze River, where modern-day Hangzhou and Shanghai are located), he brought a milk tea master from Mongolia to prepare milk tea for the court daily,” says Chiang.

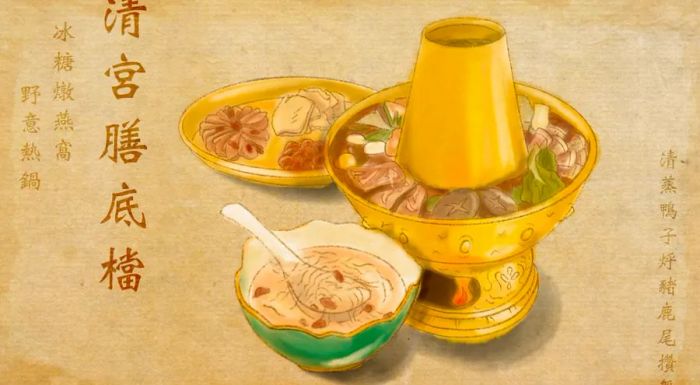

Chiang, who enjoys studying the Qing Dynasty because of the vast number of historical artifacts preserved from that time, such as texts and paintings, adds that the court also enjoyed hot pot—a traditional Chinese dish where ingredients are cooked in a simmering pot of soup stock right at the table.

“According to one palace maid, the royal family would have hot pot nearly every day for three months during the winter. It was a favorite dish,” the historian explains, pointing to an enamel hot pot from the Forbidden City displayed at the Hong Kong Palace Museum.

Chiang, who is currently preparing an upcoming exhibition on food and travel in the Forbidden City, notes that while Emperor Qianlong’s menus were recorded, researching the palace’s food history remains difficult because many sealed documents have yet to be made available to researchers and the public. (Her exhibition relies on documents already published by the Palace Museum.)

As one of the few who has ever had access to these archived documents, Zhao has published much of his research over the past few decades. He continues his work and is now compiling a book based on his findings to further unravel the mysteries of palace cuisine.

Through this extensive knowledge, Zhao has been able to reevaluate the long-standing assumptions about what was consumed inside the Forbidden City, offering a broader perspective and much-needed context. This includes the emperor’s alleged fondness for hot pot.

“Menus were typically presented to the emperor the night before for his approval,” Zhao explains.

“The menus reflected the emperor’s personal tastes but weren’t solely based on his preferences. For example, we know that Emperor Qianlong had hot pots, which were often referred to as ‘warm pots’ in the records. This might have been due to the weather and tradition, but it doesn’t necessarily mean Qianlong had a particular love for them,” he adds.

Zhao explains that during Emperor Qianlong’s reign, the imperial cuisine became much more sophisticated and varied, combining traditional Manchu dishes like roasted roe deer and pheasants with Southern flavors, particularly those from the Jiangnan region.

“The game on his menus reflects his northern heritage,” Zhao notes. “A recurring dish in his records was the Sika deer tail platter. Though the tail was a small portion, it was incredibly rich and aromatic.”

Smoked red-braised duck, fried spring bamboo shoots with pork, and bird’s nest soup sweetened with rock sugar were just a few of the popular Jiangnan dishes that frequently appeared in the Forbidden City’s royal meals.

Emperor Qianlong, along with other Qing nobility, believed bird’s nest soup—made from the solidified saliva of swallows—was a potent delicacy. It was thought to be so nourishing that researchers suggest he had a bowl every morning before breakfast.

“There are countless myths surrounding bird’s nest soup. It was a relatively new ingredient at the time,” Zhao explains, pointing out that it wasn’t even listed in a major Chinese medical encyclopedia published in the late 1500s.

According to historical records, Qianlong had two main meals a day: breakfast at 6 a.m. and dinner at 2 p.m. However, he would typically snack on bird’s nest soup or something similar as soon as he woke up at 4 a.m. before his main meal and work.

Later in the evening, while reviewing reports and requests from across the empire, he would have a light meal around 8 or 9 p.m., usually consisting of eight to ten small dishes.

“He usually dined alone, except during his late-night snack, when he might share the meal with a consort who would accompany him to bed,” Zhao says.

“The emperor's two main duties were to eat well and sleep well – ensuring his health to produce heirs,” says Zhao.

While being the ruler granted him access to the finest ingredients, the emperor didn’t always indulge. Both Zhao and experts at the Hong Kong Palace Museum agree that dining in the Forbidden City wasn’t as extravagant as many believe.

“The emperors were raised in a highly disciplined environment,” explains Wang from the Hong Kong Palace Museum. “Their diet was designed to be healthy, studied by experts, and tested by history.”

Wang points out one of the biggest misconceptions about dining in the Forbidden City: “People assume the emperors must have eaten an endless variety of dishes, especially with the legendary Manchu-Han Banquet story.”

The legendary Manchu-Han Banquet.

The myth of the extravagant Manchu-Han Banquet – often cited as a prime example of the imperial family's dining habits – is closely tied to Empress Dowager Cixi, a former concubine who wielded absolute power over China for nearly 50 years until her death in 1908.

Cixi played a pivotal role in the final phase of Zhao’s research on Forbidden City cuisine. To understand how she inadvertently contributed to one of the biggest misunderstandings about Chinese food today, it’s essential to consider the unique political and social context of China leading up to its reopening in the late 1970s.

This was a time of political and economic isolation for China, following the Communist victory in the civil war of 1949.

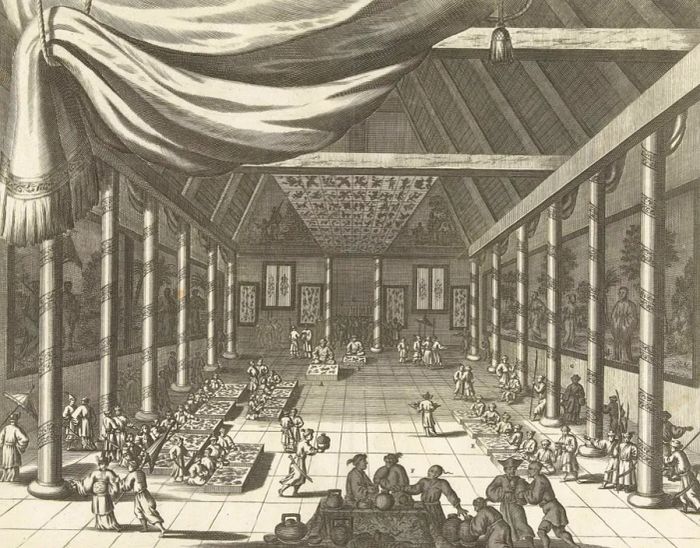

By a twist of fate, national pride in Chinese cuisine surged around a legendary banquet known as the “Manchu-Han Feast” (or Man Han Quan Xi). This feast, which originated in the Forbidden City, was popularized during an exhibition in Guangzhou in the 1950s.

In 1957, at the inaugural China Import and Export Fair in Guangzhou, one vendor displayed a lavish banquet spread for all to see,” recalls Zhao.

“Of the few foreign delegations present, Japanese businessmen were particularly intrigued. At the time, Japan’s economy was rebounding swiftly after World War II, and they were eager to learn about this extravagant feast,” says Zhao.

“The curious staff member consulted with his boss, who then turned to the chef. Neither had any clear answers, but the chef, eager to provide an explanation, stated, ‘This is called the Manchu-Han Banquet, and it was created by the emperor.’”

The Japanese businessmen were reportedly captivated by this explanation.

From that point onward, the Manchu-Han Feast became linked to the imperial court and its lavish dining, and Zhao notes that it quickly became a major food trend in Japan.

Numerous food enthusiasts and research teams flocked to communist China, eager to uncover the secrets behind this mysterious imperial cuisine that, in reality, never existed.

“While mainland China initially resisted spreading such capitalist ideals abroad, Hong Kong restaurateurs saw it as an incredible business opportunity,” Zhao explains. (At the time, Hong Kong was under British rule.)

In 1978, a Japanese television station partnered with a Hong Kong restaurant to recreate and broadcast a grand Manchu-Han feast live. The extravagant banquet was divided into four separate meals over two days.

This broadcast only served to reinforce the myth, leading many to wrongly believe that the emperor's banquets included 108 dishes spread over two days.

Following China's reopening, ambitious chefs on the mainland proudly claimed they could outdo the original feast, with one chef even preparing a banquet of 1,080 dishes, according to Zhao.

The allure of this enigmatic imperial Chinese cuisine quickly spread throughout East Asia. Even Zhao himself couldn't escape its grip.

“That’s when I decided to uncover the truth,” Zhao recalls, explaining that these grand banquets sparked his curiosity about the culinary practices of the Forbidden City.

The extravagant feasts of Empress Dowager Cixi.

So, how does Empress Dowager Cixi fit into this picture?

As the true power behind the last few emperors of the Qing Dynasty until her death, Cixi was infamous for her opulent lifestyle and her love for sophisticated Han Chinese dishes.

“It was the most decadent period of the Qing Dynasty. The number of courses in their daily meals grew from 18-23 to 25-28,” Zhao notes.

An avid hostess, she regularly organized grand ceremonial feasts. While no official Manchu-Han Banquets were held, various other imperial banquets took place throughout the centuries – though none were as elaborate as the myths suggest.

The most renowned banquet style was the 'Tian An Yan' (Increase Peacefulness Banquet), a fusion of two traditional feasts – the meat-heavy Manchu banquets and the more refined Han style featuring bird's nest soup and seafood delicacies.

“Feasts with bird’s nest as the star included rare seafood delicacies like shark fins, sea cucumbers, dried scallops, and fish lips. Roasted meats, particularly roast pork and duck, were common,” explains Zhao.

“These banquets were meticulously planned, with strict guidelines. Each feast included two hot pot dishes, four large bowls with auspicious names, four smaller bowls, six food plates, two platters (like sliced Peking duck or suckling pig), four varieties of pastries and buns, one noodle dish, one soup, and a fruit platter,” Zhao adds.

“Even the grandest version of the Tian An Yan during that period typically featured no more than 28 dishes – a far cry from the 108 dishes often depicted by modern media,” notes Zhao.

As the reputation of Empress Dowager Cixi’s government became increasingly associated with excess and corruption in the final years of imperial China, affluent individuals began creating their own versions of 'imperial banquets' inspired by the Tian An Yan, which they dubbed 'Manchu-Han Banquets.' This trend contributes to the confusion about their link to the emperors of China.

The Journey that Led Zhao to Food History

Despite his extensive study of food history, Zhao does not consider himself a foodie. In fact, his deep interest in food history stems from the traumatic experiences he endured as a child during the three-year famine following the Communist regime's disastrous Great Leap Forward economic policies in the late 1950s.

“The painful memory of enduring hunger and the devastating loss of millions of lives during the 1960s famine continues to haunt me, especially the constant stomach cramps that marked that period,” Zhao reflects.

“I consider myself fortunate to have survived, and it profoundly shaped my views on food,” Zhao reflects.

Because of these experiences, Zhao believes that understanding our historical relationship with food is crucial to improving global food security in the future.

“Studying the history of food is essential to understanding our food culture with authenticity,” says Zhao.

“Studying food culture not only promotes a country’s culinary heritage but also prompts reflection on our current food policies. Everyone enjoys a delicious meal, but I didn’t become a food historian for indulgence. It’s about awareness and responsibility, and a commitment to uncovering the truth. Today is built on the past, which is why understanding history is essential to who we are now and who we will be in the future,” says Zhao.

1

2

3

4

5

Evaluation :

5/5