Gazoz: The Signature Drink of Modern Turkey

ThereThere are numerous beverages to enjoy in Turkey. In 1555, Damascene merchants established the first public coffeehouse in İstanbul, serving coffee sourced from Yemen. Salep, made from ground orchid root and hot milk, is a winter favorite. Şalgam, a fermented turnip juice, is found in southern Anatolia and at kebab shops nationwide. Turkish tea is often served in ornate tulip glasses after meals, while ayran, a savory yogurt drink, and raki, a twice-distilled spirit made from grapes and aniseed, vie for the title of the national drink.

While each of these drinks serves a unique purpose, the diverse flavors of Turkey come together in gazoz, a type of soda that features an encyclopedic variety across regions, showcasing local culinary traditions. Today, vibrant blue, bright yellow, and fiery orange bottles can be found in cafes and local markets, offering flavors such as bubble gum, grape, rose hip, banana, honey, kaymak (clotted cream), and many more.

More than just a drink, gazoz reflects Turkey’s unique cultural crossroads, emerging as the nation transitioned from empire to republic in the 20th century. The beverage continues to adapt, introducing new flavors to the rich array of Turkish offerings.

From sweet apricots to bitter almonds, the flavors of gazoz capture the essence of Turkey’s diverse cuisines.

Just as different Italian regions have their own unique pastas and American cities boast various styles of barbecue, the vibrant array of gazoz flavors creates a culinary map of Turkey. Although some brands are available nationwide and even exported, most gazoz is produced and enjoyed locally, reflecting a deep sense of community pride in a nation where origin matters greatly. You can find bottles designed like local landmarks, such as Beyoğlu Gazozu, which is shaped like İstanbul’s iconic Galata Tower, or brands named after local slang, like Noriyon Gazoz (essentially meaning 'What’s Up, Gazoz') from the central Anatolian town of Nevşehir.

Each region utilizes its unique mineral water and local ingredients to craft its gazoz. The coastal city of Mersin is known for its blueberry gazoz. Bağlar Gazoz, hailing from a neighborhood in the Black Sea town of Safranbolu, produces a saffron and ginger soda that pays homage to the region's famed crimson spice. Kayısı Kola, from Malatya, the apricot capital of the world in eastern Anatolia, offers a refreshing apricot and basil drink. Meanwhile, Marmaris, nestled along the Turkish Riviera, is celebrated not just for its beaches but also for its extensive pine forests, which infuse a locally named Marmaris gazoz with unique flavors.

'We crafted a gazoz blending bitter and sweet almonds,' shares Kadir Ünal, owner of Datçam in the narrow Datça peninsula, renowned for its almonds. 'We knew it would be a delightful combination.' He proudly notes that both locals and tourists prefer it over Coca-Cola and even water.

Assorted flavors of gazoz.

David Lombeida

Assorted flavors of gazoz.

David LombeidaThe story of gazoz, a beverage for 20th-century Turkey

Long before soda became popular in Turkey, locals enjoyed sharbat, a sweet concentrate made from flowers or fruit, which originated in Persia. This drink eventually made its way to Europe and South Asia, leading to a range of similar drinks and desserts. Europeans introduced carbonation, mixing bubbly water with homemade syrups, fruits, and herbs. The French called it gazeuse, and when Ottoman merchants brought this fizzy version back to Turkey at the end of the 19th century, it was named gazoz.

In the early 20th century, equipment for making sodas began to appear in İstanbul’s Sirkeci and Karaköy neighborhoods. Various communities, including Greeks and White Russians, started creating their own brands. Records from 1938 indicate that İstanbul had four soda factories: Olympos, Bomonti, Kocataş, and Yalova.

Along the Turkish coast, the city and region of İzmir, known for its mineral water, quickly emerged as a significant soda hub. The Churchill, a refreshing mix of sparkling mineral water, lemon juice, and salt named after the city’s native son Churchill Ahmet, became a signature drink and helped popularize the soda category. From there, the gazoz trend spread throughout the country.

“We already had a rich tradition of sharbats, so enjoying something sweet was common,” remarks Turkish food writer Aylin Öney Tan. “But with gazoz, it shifted to a focus on the fizz, and every city developed its unique twist.”

Posters featured at Avam Café.

David Lombeida

Posters featured at Avam Café.

David LombeidaDuring this time, Turkey was undergoing significant political, legal, and social changes in its quest to establish a secular nation-state. Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the Republic's founding father, was so taken with the therapeutic qualities of mineral water from the Anatolian town of Gazlıgöl during the War of Independence that he donated a factory there to the Turkish Red Crescent, which used it to bottle soda for their humanitarian efforts.

The drink aligned perfectly with the government's inclination towards European-style modernity. It also supported nationalization initiatives, as it was commonly sweetened with local sugar beets, which became the primary sugar source post-Republic. Soda companies expanded south and east, often transported by donkey in regions lacking vehicles. Gazoz evolved into a symbol of modern Turkey.

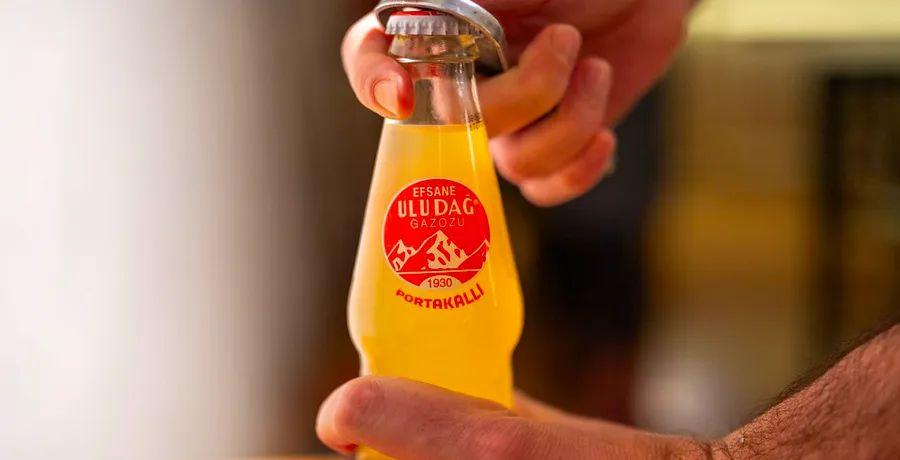

“Wherever Turks are in the world, there is Uludağ Gazoz,” proclaimed Uludağ, a brand that began as Nilüfer soda in the northwestern city of Bursa in 1930. In the south, the mayor of Adana inspired Suleyman Ayman to name his emerging brand Zaman, meaning “time” in Turkish, reflecting the modern era enveloping the city and the broader Cukurova region.

“People were seeking something fresh and different in their lives, including their drinking choices,” notes Zafer Yenal, a sociology professor at Boğaziçi University. “This was also tied to the diversification of leisure activities and the rise of public spaces and communal life.”

Gazoz swiftly overtook its rivals in both new and traditional social venues. Truck drivers delivered not just crates of soda and ice to cities but also news, lessening the need for social hubs like coffeehouses. Turks began enjoying gazoz while watching football games or relaxing after a session at the hamam or at the cinema. Children entertained themselves in the streets with bottle caps, while adults used it to sober up or to alleviate stomach issues when paired with aspirin.

“It was a drink for everyone, becoming accessible to all due to its low cost. At that time, it brought together all segments of society — both rich and poor,” says Burak Serkan Çetinkaya, a chef and filmmaker behind the documentary Kapak Olsun, which explores gazoz culture.

By the 1960s, there were thousands of local producers scattered across the country.

So many options.

Joshua Levkowitz

So many options.

Joshua Levkowitz The diverse bottle caps of gazoz.

Joshua Levkowitz

The diverse bottle caps of gazoz.

Joshua LevkowitzGazoz and Goliath: Confronting the soda giants

While the War of Independence paved the way for gazoz’s popularity, the Cold War nearly led to its decline. Turkey became a NATO member in 1952, welcoming American soldiers, tourists, and consumer goods. The behemoth Coca-Cola arrived in 1964 with its first factory in İstanbul, quickly followed by Pepsi just two years later. Local flavors struggled to compete against the dominating citrus, cinnamon, and vanilla flavors of these global beverage leaders. By the decade's end, Coca-Colonization was in full swing, as the company organized Turkish pop festivals and launched bottle cap promotions for customers to win televisions and trips to Europe.

Some gazoz brands attempted to imitate their global competitors by replacing unique flavors with colas. While a few, such as Uludağ, Niğde, and Çamlıca, successfully transitioned from local to national production and distribution, most struggled against the Americans’ sophisticated supply chains and extensive advertising budgets.

This competitive landscape has given rise to many myths. Allegations circulated that international soda companies pressured the Turkish government to impose regulations that eliminated manual labor in soda production, effectively pushing out small producers. Others claimed that conglomerates employed thugs to vandalize local factories or that Coca-Cola coerced Şişecam, the leading glass manufacturer in the country, into a decade-long exclusive contract, compelling gazoz makers to source pricier bottles from neighboring nations. Turkish leftists viewed Coca-Cola and Pepsi as tools of American hegemony. A 1965 cover of Yön, a leftist magazine, cautioned, “Coca-Cola is poison, do not drink it!”

Only about 10% of gazoz producers survived this tumultuous period, with more shutting down in subsequent years. Although Suleyman Ayman’s son Ali managed to keep the family business afloat for many years, Zaman ceased production of its signature red-and-white gazoz bottles in 2023, as his children chose not to continue the legacy.

“Zaman will forever linger in people’s memories,” he reflects with a touch of sadness.

The resurgence of gazoz

Gazoz continues to attract loyal fans. Many consumers perceive these brands as refreshing and authentic compared to other sodas, purchasing gazoz as a way to support local culinary traditions. For example, Çetinkaya always makes a point to try the local gazoz whenever he visits a new city in Turkey.

At a deeper level, as globalization threatens the country’s unique cuisines and independent brands, artisanal gazoz symbolizes a sweet form of resistance. Amidst the cultural and political divides and economic challenges facing Turkish society, gazoz offers an escape, evoking the nostalgia that many Turks cherish.

“These days, people have low expectations for the future,” says professor Yenal. “So there’s a renewed interest in the past. Gazoz serves as a means to ground people, providing a sense of stability.”

Much of the nation’s anxiety stems from rapid urbanization over the past two decades. Between 2002 and 2018, the share of the population residing in rural areas plummeted from 35% to 16%. For the millions who have moved, a taste of home is often just a bottle of gazoz away.

“People seek out the gazoz from their childhood,” shares Ufuk, a barista at Kapa Café, which features 85 different brands from around the country. While this variety might seem at odds with the locavore ethos of gazoz, it serves as a vital resource for longtime enthusiasts and a discovery hub for newcomers.

The lively atmosphere at Avam.

David Lombeida

The lively atmosphere at Avam.

David LombeidaIt's not just older Turks who are on the lookout for nostalgic flavors. Many days, young university students flock to Avam Café in İstanbul to grab a few bottles from the coolers. They savor their gazoz amidst vintage posters depicting joyful women dancing in miniskirts while enjoying cherry soda.

“Gazoz producers laughed when I first ordered crates of their soda for the café. They didn’t believe anyone would buy it,” recalls Ulas Bahçıvancı, who founded Avam in 2012.

In addition to cafés like Avam and Kapa, a new wave of gazoz producers has emerged, offering innovative flavors that cater to contemporary palates. Erenköy Gazozu, crafted in the trendy Kadıköy neighborhood on İstanbul's Asian side, features small-batch flavors such as cardamom-lemon and nutmeg-anise. Meanwhile, Şirince Gazozu, from the picturesque village of Şirince south of İzmir, produces elderberry-peach soda alongside a flavor made from a recently revived indigenous strain of white grapes. Others, like Maki, continue to produce gazoz under the label of seltzer.

Bahçıvancı highlights that café owners are rediscovering the art of crafting soda from fresh ingredients. Sevda Gazozcusu, a soda shop with four locations, creates its own unique gazoz flavors, while Gazvoda Cafe in Çanakkale serves handmade sodas in stunning beryl and azure hues.

These newcomers face significant challenges from international brands, but they clearly demonstrate that there is still plenty of life and effervescence left in gazoz.

Joshua Levkowitz covers migration and fast-food culture in the Middle East and Mediterranean, drawing inspiration from Louisiana.David Lombeida is a photojournalist and filmmaker based in Istanbul, Turkey, focusing on topics related to economy, conflict, and migration.

1

2

3

4

5

Evaluation :

5/5