How a trip to the Caribbean deepened my connection to my West African heritage

Poet and author Nii Ayikwei Parkes realized during a visit to Guadeloupe how the threads of his family's British, West African, and Caribbean narratives intertwine.

While visiting Grande-Terre, the second-largest island in the Guadeloupe archipelago, I discover that my Tante Armelle has organized a family gathering with her siblings, their children, and even her 100-year-old mother.

We are welcomed by her elder brother, whose lovely home is perched on a hill overlooking lush greenery. He greets us with the island's signature cocktail, P’tit Punch, offering a selection of delightful rhums agricoles, including local favorites like Reimonenq, Longueteau, and Damoiseau. As we sit down for a meal, the dishes are served: rice cooked with peas, reminiscent of Ghana and other Caribbean locales, fragrant sauces accompanied by Scotch-bonnet peppers, and perfectly cooked meat... I close my eyes and inhale deeply.

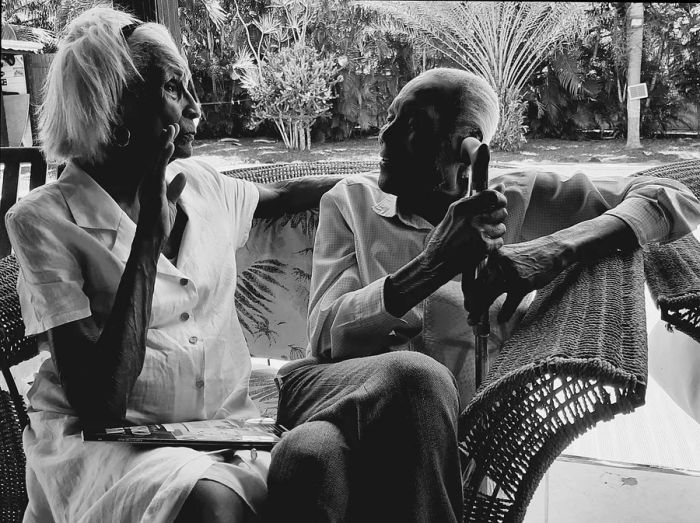

Reconnecting with family elders in Guadeloupe © Nii Ayikwei Parkes

Reconnecting with family elders in Guadeloupe © Nii Ayikwei ParkesI could be anywhere in West Africa. I’m not far from home at all.

********

When my parents resided in London, my father would conclude his job application letters with a phrase that many Ghanaians and fellow Commonwealth citizens rarely needed: “for clarity, I am a Black man.” He had experienced too many job interviews where, upon hearing the name Jeremiah Parkes and seeing him, interviewers’ expressions would shift in shock, and the opportunity would vanish into the surprise that left their mouths agape. In this way, despite growing up speaking a Ghanaian language in England, he found more in common with people from the islands of Trinidad and Tobago, Jamaica, Barbados, and St Vincent, who did not bear names like Amoako or Olugbodi that hinted at their Blackness on paper. This shared trauma was not coincidental: in my debut poetry collection, The Makings of You, I express this in the poem “Zion Train”:

Imagine now how /

I was surprised to discover that my name, Parkes, /

actually traces back to a Jamaican ancestor who returned to Sierra Leone /

having come as a soldier…

This revelation, drawn from a careful reading of Christopher Fyfe’s A History of Sierra Leone (where my great-grandfather was engaged in public affairs), provided a deeper understanding than what I had known growing up—that our European surname came from our grandfather who had moved to Ghana from Sierra Leone. Later, in 2018, I discovered that my Jamaican ancestor, who had migrated to Sierra Leone, had stopped in Guadeloupe to bring his son, Thomas—likely the first Parkes to establish a family back on the African continent after enduring years of enslavement.

The connection to Guadeloupe seemed puzzling, as the British and French were not known for collaboration during their imperial pursuits. However, since Thomas’ mother did not accompany him, this Guadeloupe link suggested the possibility of him having siblings there. Therefore, while I was exploring various Caribbean nations for my research at Harvard University’s Hutchins Center, I seized the chance to visit the archives on the largest island of the archipelago, Basse-Terre.

********

The lively center of Pointe-à-Pitre, Guadeloupe © byvalet / Shutterstock

The lively center of Pointe-à-Pitre, Guadeloupe © byvalet / ShutterstockIn a surprising turn of events, my first visit to Guadeloupe is met with family. After arriving by ferry from St Lucia, where I had been immersed in the French-based Kreyol that coexists with English, I step off the pier at Pointe-à-Pitre to the warm embrace of Tante Armelle. Though she bears a striking resemblance to some of my aunts in Ghana, I’ve never met her before—she is the mother of my friend Hervé, who I have known since our student days in Dijon in 1995. Having spoken about me for nearly three decades, I’ve woven myself into the fabric of their family lore, making me part of the family. Our time together is brief; after only a few hours, I rent a car and navigate the impressive curves of Guadeloupe’s roads, passing extensive banana plantations on my way to Basse-Terre.

The following noon, I arrive at the archives in Gourbeyre with no clear objective, just a feeling that I must grasp the archival system to utilize it effectively. After filling out a form for a membership number, I engage in conversation with one of the older archivists and learn that Basse-Terre was seized by a British expeditionary force in 1759 and remained under their control until 1763. Further investigation reveals that this force primarily comprised African men who later became the first members of the West Indies Regiment. Suddenly, everything clicks: this explains how a man from Jamaica fathered a child with a woman from Guadeloupe and later, through his military service, was able to return for his son and offer him a new life in Sierra Leone.

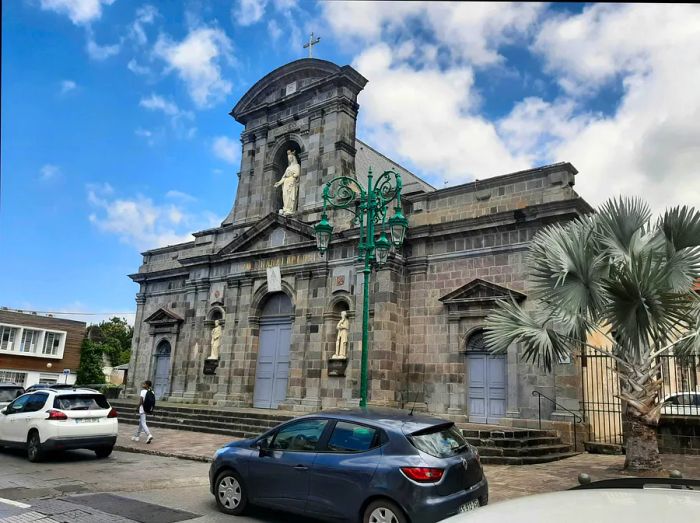

The Paroisse Notre-Dame de Guadeloupe, where the author’s ancestral records are likely archived © Nii Ayikwei Parkes

The Paroisse Notre-Dame de Guadeloupe, where the author’s ancestral records are likely archived © Nii Ayikwei ParkesSierra Leone is the point where my Caribbean narrative reconnects with its African roots.

Azúcar, the author’s latest book, is set on a fictional Caribbean island and is now available in paperback

Evaluation :

5/5