In a secluded Canadian national park, Inuit guardians guided our journey.

Our landing gear splashes down in Goose Bay, known locally as 'Goose'. The heavy rains that surround us are why we arrived a day early; getting stuck due to weather is common when awaiting the final leg to the ancestral territory of the Northern Labrador Inuit, located over 900 miles north of St. John’s, Newfoundland. Fortunately, by morning, the sun breaks through and our flight to the Torngat Mountains Base Camp and Research Station is ready to take off.

Co-pilot Brody secures the stairs hatch and climbs into the cockpit of our vintage red Twin Otter from the 1960s. Engines roar to life, propellers spin. We’ll make a quick stop in the remote Inuit settlement of Nain to refuel before heading to the Cold War-era airstrip at Saglek Bay. Although the runway is long enough for jets, it’s mostly deserted now, with only these Air Borealis flights operating. Other planes might traverse this route more swiftly and smoothly at higher elevations, but for the next three hours, I’ll enjoy the opportunity to appreciate this captivating landscape from above.

The breathtaking aerial views of the Torngat Mountains' landscapes are simply stunning © Liz Beatty

The breathtaking aerial views of the Torngat Mountains' landscapes are simply stunning © Liz BeattyStepping into a wilderness steeped in history

Beneath a canvas of azure skies, the vibrant red wing of our plane contrasts against a tapestry of rivers, estuaries, islands, and coastal mountains below. As we near Canada’s tallest peaks east of the Rockies, the landscape begins to rise up to meet us. Forests fade away, giving way to ancient, bald rock, etched and marked by long-extinct glaciers—some of the oldest formations on the planet, nearly four billion years old. Enormous icebergs drift by, likely calved from Greenland’s glaciers. We catch our first glimpse of polar bears, a mother guiding her cub across a rocky island that seems to float in the North Atlantic.

While the breathtaking beauty of this wild haven beckons, it’s the deeper story that matters most. The painful history of Indigenous relocation is a familiar tale throughout Canada. Yet, in this moment, I find myself grappling with the complexities of that history and the unfolding narrative. Ahead lie the personal accounts of Labrador Inuit returning to their ancestral lands, the efforts of visiting scientists collaborating with traditional Inuit Knowledge Keepers to combat climate change, and the awakening of Inuit youth as they discover how their ancestors once lived. As we unload our equipment in Saglek, I ponder my role as a traveler. Am I merely an observer with privilege? What can I offer to this unfolding story?

The insights I seek are only a short helicopter ride away.

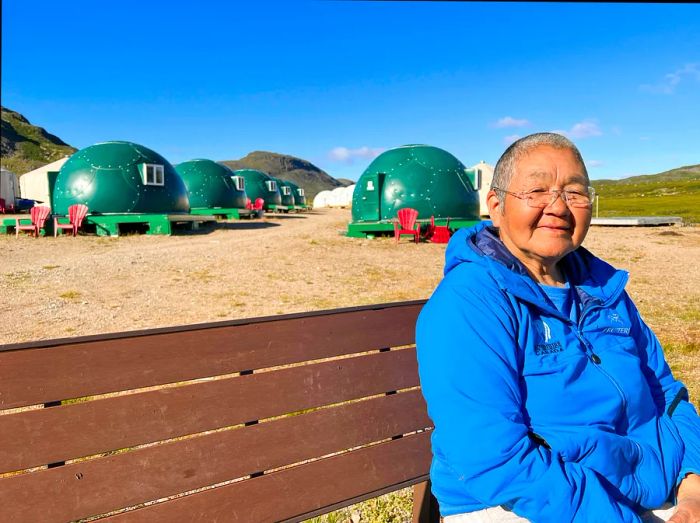

Youth accommodations available at the Torngat Mountains Base Camp and Research Station © Liz Beatty

Youth accommodations available at the Torngat Mountains Base Camp and Research Station © Liz BeattyA hub where Knowledge Keepers and researchers converge

In a swift ascent, we veer sharply left, soaring over a mountain ridge. Within moments, a cluster of white, orange, and green geodesic domes, octagonal glamping units, and larger functional buildings come into view in the valley below, close to the water's edge. This is the Torngat Mountains Base Camp and Research Station, arguably one of the planet's most extraordinary gathering places.

Established in 2006, this subarctic outpost lies just beyond the southern boundary of Torngat Mountains National Park on Labrador Inuit Lands. It’s a collaborative effort between Air Borealis and the Nunatsiavut Group of Companies, in partnership with the self-governing Inuit Nunatsiavut Government. The site was designed to provide a welcoming base for visitors—both non-Inuit and primarily Inuit elders and their descendants returning to reconnect with their heritage. It also serves as a venue for Inuit Knowledge Keepers, Inuit researchers, and scientists from around the globe to collaborate on environmental and archaeological projects. Each summer, national park staff operate from here as well. Formed in 2008, the Torngat Mountains is one of Canada’s newest national parks and the only one entirely managed by Inuit.

Park staff members Stephanie and Lindsey fish for Arctic char in North Arm © Liz Beatty

Park staff members Stephanie and Lindsey fish for Arctic char in North Arm © Liz BeattyA towering electrified fence encloses our area, charged each night with 15,000 volts to safeguard us from a robust population of polar bears, as well as the notably large and opportunistic black bears found in Northern Labrador. Parks Canada Media Officer, Lindsey Moorehouse, cautions us, 'Avoid touching the fence, hanging laundry on it, or most importantly, venturing beyond it without the supervision of an armed Inuit Bear Guard.” Consequently, Inuit Bear Guards Joe, Maria, and others will accompany us for the next three days. This is reassuring but raises a significant question — how can we, about 550 travelers from late July to early September, contribute meaningfully amidst a group with such a clear and vital mission?

Cultural Ambassador and Bear Guard Maria prepares panitsiak bread for frying, while a Parks Canada staffer cooks freshly-caught char © Liz Beatty

Cultural Ambassador and Bear Guard Maria prepares panitsiak bread for frying, while a Parks Canada staffer cooks freshly-caught char © Liz BeattyGathering in the visitor's tent.

Beyond the research lab, this week includes Parks Canada staff, a youth program, Knowledge Keepers, Bear Guards, camp crew, and the Torngat Mountains National Park Co-Management Board conducting their annual meetings on-site. Returning elders also take on the role of Cultural Ambassadors, connecting everyone with traditional Inuit ways. As visitors, we find ourselves immersed in this vibrant mix during group meals, around the fire pit, enjoying char sandwiches on mountain hikes, helicoptering to 3,000-foot waterfalls, and attending a researcher’s presentation on our first evening.

The MASH-style visitor tent is packed to capacity. Dr. Robert Way, Assistant Professor in the Department of Geography and Planning at Queen's University in Kingston, Ontario, shares his findings on permafrost loss at a site within the park, which is causing soil to slough into Torngat waterways. Inuit elder Sammy Unatweenak contributes, stating, “I remember no melting for 30 years here, and now we see significant changes.” Other elders also speak up, sharing generations of knowledge that frame the findings of visiting scientists. The mutual respect in the room is palpable.

Later, I observe experienced Inuit researchers measuring environmental contaminants with the assistance of youth group volunteers. The insides are extracted from open char bellies on the stainless-steel lab counter. This is the domain of Research Manager Michelle Sanders, the first Inuit woman to hold this role, leading an all-women Inuit research team.

Inuit games, featuring high kicks, hopping, and leg wrestling, require balance, strength, and control — closely reflecting the skills needed for successful hunting © Liz Beatty

Inuit games, featuring high kicks, hopping, and leg wrestling, require balance, strength, and control — closely reflecting the skills needed for successful hunting © Liz Beatty'There has definitely been a transformation in our approach compared to just 10 years ago,” Michelle states. 'Now we not only guide the work of visiting researchers but also actively participate in it ourselves.” Beyond this newfound self-determination, Sanders emphasizes that her team offers a distinct perspective to southern researchers: “Inuit life sees everything as interconnected. Health is tied to the land, which in turn influences mental well-being. We adopt a holistic perspective in our research.”

It’s encouraging to see that our tourism dollars are fueling such initiatives. Yet, I still grapple with feeling like just a bystander, an outsider in this community focused on reconciliation. Prior to my arrival, I delved into the Canadian government’s tragic history with the Northern Labrador Inuit, hoping that this knowledge would somehow justify my presence. However, understanding the facts is one thing; experiencing their significance in the lives of those affected, in the very place it unfolded, reveals that the storytelling is ultimately theirs to share as they choose.

I come to understand this directly from Maria.

Enjoying a moment with Maria at the Base Camp firepit © Liz Beatty

Enjoying a moment with Maria at the Base Camp firepit © Liz BeattyThe sorrow of displacement

Maria Merkuratsuk’s ancestors flourished for millennia, living nomadically in this enchanting landscape. This way of life was disrupted when her parents, among many Northern Labrador Inuit, were relocated to the German Moravian mission in nearby Hebron during the early 1950s. Established in 1818, the Hebron mission has a complex legacy, being one of eight missions in Northern Labrador aimed at spreading Christianity among the Northern Inuit. Nevertheless, Hebron is also recognized by Inuit as The Great Bay—an ancient gathering place and hunting ground for Northern Inuit communities. It was here that Maria’s father and others maintained their connection to their heritage and the homeland they cherished.

The deeper tragedy unfolded in 1959, when the entire Hebron community was abruptly and violently dispersed to unfamiliar settlements further south. Families were torn apart, moved to places where they lacked ties to the land and their cultural roots. Maria’s father never fully recovered from this upheaval, and she grew up internalizing his trauma.

During dinner on my first night, I attempt to engage Maria in conversation to learn more about her family's history. However, she seems to prefer keeping her distance. Later, some staff members suggest that she might be willing to share a few moments with me during our long journey to North Arm tomorrow. We shall see.

Captain Willy Fox, left; the view from the back of the Safe Passage, right © Liz Beatty

Captain Willy Fox, left; the view from the back of the Safe Passage, right © Liz BeattyInuit Captain Willy Fox greets us aboard his trawler Safe Passage on a cool, misty morning. Raised in Nain, he has been navigating these waters for over three decades. Today, he guides our journey into the breathtaking fjords, flanked by ancient mountains that characterize this expansive park. The landscape before us is nothing short of stunning. However, it’s the opportunity to experience this homeland through the perspectives of those rediscovering their heritage that will profoundly change us.

Below deck, an Inuit staff member from Parks Canada crafts sealskin booties for a friend's baby while Lindsey enjoys tea at the same table. Having worked here for seven seasons, she, like many others on board, is also reconnecting with her heritage.

Parks Canada staff members sip tea and sew sealskin booties to pass the time as we venture deeper into Torngat Mountains National Park © Liz Beatty

Parks Canada staff members sip tea and sew sealskin booties to pass the time as we venture deeper into Torngat Mountains National Park © Liz Beatty“It fills me with such strength to know that my ancestors lived this life without modern comforts, and they were resilient and wise enough to flourish,” she smiles. “And in one of the most incredible places on earth.”

Maria soon makes her way below deck as well. I invite her for a tea chat, but she firmly states that her stories are meant for the entire group today. Fair enough. Later, I spot her on the deck sharing stories about polar bear hunting, mermaids, and other childhood tales from these shores. I join the researchers, camp staff, and Parks Canada employees, all captivated by her words.

Researchers, videographers, park staff, and others catch sight of a polar bear on the shore within the park © Liz Beatty

Researchers, videographers, park staff, and others catch sight of a polar bear on the shore within the park © Liz BeattyWildlife observations

Later, at the entrance of the North Arm channel, someone spots a polar bear dozing on the beach, about 100 yards from our intended landing spot. Maria rushes to the front of our 45-ft trawler, readies her rifle, and instructs our group of about 20 to cover their ears. Her warning shot reverberates off the towering 3000-ft mountains lining the fjord. The two zodiacs piloted by fellow Bear Guards speed ahead to drive the bear further up the shoreline with bear buzzers that resemble misfired fireworks. The bear sprints but then pauses to glance back.

“He’s not in good shape,” Maria observes. “He should be more frightened.” I inquire how that might influence the bear’s actions. She responds with a mischievous smile, “He wants to eat you.” Clearly, she and her fellow Bear Guards have everything under control. This mystical 3700-sq-mile park is not wilderness to them; it’s their homeland. Maria, Joe, and the others skillfully drive the ailing bear well away from our landing area. Only half-jokingly, I ponder aloud, “How far is far enough?”

And then the festivities resume as if nothing had occurred.

Parks Canada staffer Stephanie Webb guts char on the shore © Liz Beatty

Parks Canada staffer Stephanie Webb guts char on the shore © Liz BeattyPark staffer Stephanie casts a line from the beach and reels in a massive char. Others follow suit. Within minutes, the fish are prepared for frying, and fires are lit. Maria whips up a batch of traditional fried bread known as panitsiak, which are delightfully fluffy and crispy. Someone playfully names them Northern Labrador croissants.

From the beach, Bear Guard Joe, rifle in hand, leads us in a single file through an active archaeological site filled with tagged artifacts, some dating back thousands of years. Beyond a meadow blooming with blueberries and wildflowers, we ascend to the edge of a roaring waterfall and then descend into a pristine swimming hole. Further along, a vast lake lies ahead, with another cascading stream visible across the valley.

Yet, amidst this breathtaking scenery, the true wonder lies in the effortless grace and deep connection of our Inuit hosts, guiding us safely while sharing their ties to this rugged and beautiful landscape. I come to realize that being here with Lindsey, Joe, Maria, and the others is the only way to truly grasp the profound loss of having been uprooted from such a place.

These are the narratives I will hear tomorrow.

Bear Guard Joe guides hikers back to the beach at North Arm, deep within the park © Liz Beatty

Bear Guard Joe guides hikers back to the beach at North Arm, deep within the park © Liz BeattyTelling tales of loss — and hope

I discover that Maria won’t be joining us in Hebron, perhaps I’ll see her later. While the early morning is bright and clear, we’ve been warned that strong winds will arrive by noon — too turbulent for Willy’s longliner. I gather my gear and make my way to the helipad.

We land roughly 25 yards from the long, white Moravian Church in Hebron, just a 15-minute helicopter ride south from Base Camp. The historic structure, built in 1831, appears freshly painted. Two hours here feels far too short — there are countless individuals with countless stories to share.

Engaging in conversation with Cultural Ambassador Gus Semigah at the Moravian Church in Hebron © Liz Beatty

Engaging in conversation with Cultural Ambassador Gus Semigah at the Moravian Church in Hebron © Liz BeattyCultural Ambassador Gus Semigah greets us at the church steps. Born in Hebron, he has been involved in the church's restoration since 2002. He takes us on a tour of the post office and the teacher's quarters. From the belltower, we gaze at the gray remnants of an old blubber house and the dilapidated Hudson's Bay store, gradually being enveloped by nature. Our discussion concludes in the sanctuary.

'Many people didn’t want to leave, but they felt voiceless,' Gus shares. 'The meeting took place inside the church because it’s a place where arguments are rare. The government and ministers were aware of this.' It was a calculated, ruthless strategy to relocate this Inuit community with minimal opposition.

As I leave the church, Gus bids farewell. I head inland toward a small cabin, where Lena Onalik waves to me. Lena is an archaeologist with the Nunatsiavut Government and is currently leading the Hebron Family Archaeology Project, hosting a small group of elders this week.

'It’s a race against time to bring back relocated elders and hear their stories,' she says. 'During our time here, two more elders have passed away. There are now fewer than 85 left.'

Soon, the sound of gunshots signals the elders' departure, and she rushes to the shore to bid them farewell. However, one elder chooses to remain behind.

Cultural Ambassador Sophie Keelan was just five years old when missionaries pressured her parents to relocate the family to Hebron © Liz Beatty

Cultural Ambassador Sophie Keelan was just five years old when missionaries pressured her parents to relocate the family to Hebron © Liz BeattyAmbassador Sophie Keelan was born in 1948 on Sallikuluk, also known as Rose Island, located in Saglek Bay—a site of deep significance for the Northern Labrador Inuit. She welcomes me with a friendly smile and suggests we stroll back to the church for a conversation.

We settle at a small table where the pulpit once stood. 'At that time, we lived like nomadic Eskimos,' she begins, using the outdated term still embraced by some elders. Sophie was only five when the missionaries compelled her parents to bring their children to Hebron for education. They threatened to cut off family allowances if they refused. Though she doesn't remember her family's nomadic life, she is among the few who cherish the memories of their happy existence in Hebron and the sorrow of being forced to leave at the age of 11.

“The brass band played a farewell hymn. As we boarded the ship, women and children were in tears. I was crying too. The captain began to play his accordion—‘Amazing Grace’—and we gazed upwards, trying to catch a final glimpse of our home. We watched until it was gone, until there was no trace of Hebron left,”

I ask Sophie how significant it is for elders like her to return.

'It absolutely must happen,” her voice quivers. “We all came from Northern Labrador. This is our origin, our homeland. It’s crucial that they bring it back,” she pauses, fighting back tears. Sophie envelops me in a warm embrace. I realize I can’t delay my departure any longer; the winds are intensifying.

The helicopter journey back to Base Camp from Hebron © Liz Beatty

The helicopter journey back to Base Camp from Hebron © Liz BeattyAs our helicopter ascends, I gaze down at the square, white-fenced plot that marks Hebron's graveyard. It's a once-neglected resting place for many whom I’ve met this week. I see plaques bearing the names of all Hebron residents who were relocated, alongside a formal apology. There’s also an Inuit response etched into these plaques, concluding with the words, “We forgive you.”

It’s our final night at Base Camp, and I’ve come to terms with the possibility that Maria may not want to share her story. Over the past few days, I’ve learned that everyone here processes past traumas in their own way. But then, during dinner, she unexpectedly taps me on the shoulder with a plan.

The following morning, we gather by the fire pit, just 40 minutes before my helicopter is set to depart for Saglek Bay, marking the start of my journey home.

The view from the tablelands overlooking North Arm in Torngat Mountains National Park © Liz Beatty

The view from the tablelands overlooking North Arm in Torngat Mountains National Park © Liz Beatty“It’s a very long story,” Maria begins, still hesitant. “And it all ties back to my dad’s relocation from Hebron.” What follows is a narrative of loss—of belonging, identity, and deep generational trauma—interwoven with remarkable hope and resilience. She recounts the profound effects of her father being forced from his homeland in 1959 and moved to unfamiliar communities, disconnected from the people and the land. “He never fully recovered,” she reflects. “My father carried so much hurt and anger. He lived the rest of his life feeling that the world was against him.” She adds, “His pain and anger resonate within my siblings, but I’ve grown weary of being angry myself.” When I ask her what it means to be part of Base Camp and to share the story of relocation, she pauses for a moment, takes a deep breath, and replies, 'Talking about it today is helping me heal. I’m learning to forgive what happened to my family so I can lead a good life.”

As I buckle up in the helicopter, I reflect on how Maria and so many others have opened my eyes to this Place of Spirits. Each of them has authentically revealed at least one profound purpose in my visit—to bear witness, unfiltered, to the beauty and the shadows, the persistent despair, and the remarkable resilience all coexisting within this extraordinary community. As Base Camp fades behind the mountain ridge, a sense of gratitude fills me for having been part of this experience, even if just for a few days.

The Torngat Mountains Base Camp and Research Station operates from late July to early September in 2023.

1

2

3

4

5

Evaluation :

5/5