In New Mexico, Wealth Blossoms from Nature

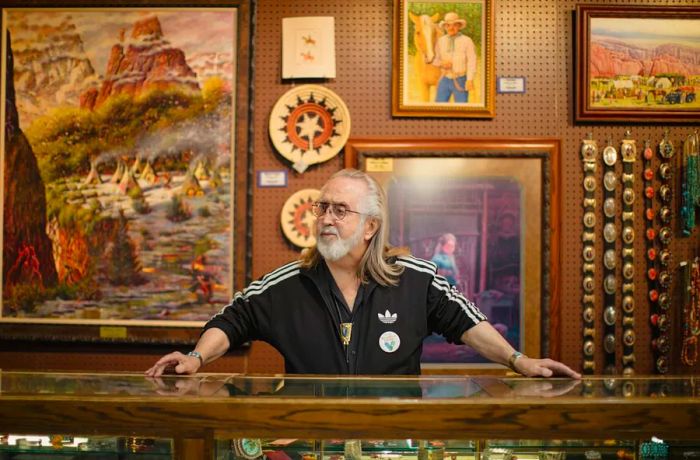

EllisEllis Tanner established the Ellis Tanner Trading Company over 50 years ago in Gallup, New Mexico, a natural progression from his upbringing in a family of Native American art traders spanning four generations. His gallery features murals of notable Navajo figures and showcases Native American jewelry and crafts in glass cases. However, what truly excites Tanner, even after decades in the business, is the trading of small, dark piñon nuts. 'I've seen my fortunes rise and fall with piñon trading,' he shares.

Tanner’s gallery sits along Highway 602, just north of an area referred to as the Checkerboard. The landscape here appears sparse, dotted with clusters of forest-green piñon pines and twisted cedars. As the winding road smooths out, it reveals stunning downhill views of rugged bluffs on the way to Zuni Pueblo. Up close, the trees thrive, forming a lush canopy in their unique high-desert setting.

Gallup, New Mexico is situated within a diverse land area known as the Checkerboard.

Gallup, New Mexico is situated within a diverse land area known as the Checkerboard.The Checkerboard area consists of a mix of land ownership types, as its name suggests—tribal, state, and private lands exist in close proximity. This 'checkerboarding' began in the mid-1800s when Navajos were relocated to reservations and assigned individual plots for farming, while other parcels were sold off to railroad companies and private buyers. Today, stepping in any direction could place you on land governed by a different jurisdiction altogether. This varied land designation presents challenges, especially when it comes to obtaining permits for construction or utility services. However, a significant advantage of this area, especially valued by locals in summer, is the abundance of piñon trees.

Piñon pine trees thrive in the high desert of the Southwest and yield nuts commonly referred to as piñon. These small, dark brown nuts ripen and fall from the trees each summer and autumn across the Four Corners region: Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, and Utah. To enjoy them, one must crack open the hard shell using their teeth, peel it back, and extract the pale kernel inside. This process resembles eating sunflower seeds or pistachios, but unlike those, the tough shell requires manual cracking. Although piñon nuts may look similar to pine nuts to the untrained eye, a Gallup local will quickly point out, “Pine nuts are large and bland,” says Tanner. “Piñon are small and sweet.”

The region surrounding Gallup—home to the unceded traditional lands of the Zuni, Pueblo, and Diné Bikéyah tribes—is not the only area where piñon nuts can be harvested. These trees also flourish in western California, stretch eastward through New Mexico to northern Texas, extend north through southwest Colorado, and even appear in Wyoming. However, New Mexico's culture of piñon foraging runs particularly deep due to its rich abundance. For centuries, tribes including the Mescalero Apaches, Navajos, and Puebloan communities have relied on piñon as a vital source of fat and calories. They have brewed tea from the pine needles and chewed the inner bark to stave off hunger during tough times. The piñon tree’s wood continues to be burned as incense and makes a popular souvenir from visits to New Mexico.

During peak piñon harvesting seasons, late summer transforms Gallup into a bustling hub of piñon trade. Large signs outside gas stations, restaurants, and trading posts announce that they are buying piñon. Brokers from outside the area set up along Highway 602, displaying their own handmade signs: “BUYING PINON.” Depending on the harvest yield, cars line the highways and forest roads as families flock to abundant piñon trees. People spread blankets on the ground, sorting through the fallen nuts from sticky pine cones, engaging in this tradition that has evolved into a thriving seasonal economy for many New Mexicans.

Ellis Tanner, a piñon dealer, is a fourth-generation trader of Native American art in New Mexico.

Ellis Tanner, a piñon dealer, is a fourth-generation trader of Native American art in New Mexico. In peak seasons, road signs in this area of New Mexico announce the buying and selling of piñon.

In peak seasons, road signs in this area of New Mexico announce the buying and selling of piñon.“In my view, the Almighty placed piñon here for the Navajo people,” Tanner states. “If you ever get the chance to see a Navajo family harvest piñon, pause what you’re doing, grab some lunch, and watch. It’s a family affair.” Local lore suggests that especially abundant yields of piñon happen only once every four years. Picking the best nuts requires precise technique: the piñon must be gently rolled between three fingertips. A heavy nut indicates quality, while a light one is a dud. The best way to harvest piñon involves spending hours beneath the trees, perhaps with a small stool, and feeling each nut individually. The value of piñon also depends on the timing of the drop: once they fall, the nuts are good for only about a month.

For many years, piñon served as a vital cash crop for New Mexico. Locals often say, “Piñon is like gold.” Consequently, these small nuts can fetch a high price if picked and sold to the highest bidder. In the summer of 2020, piñon gatherers were selling nuts to local traders in Gallup for $15 per pound. If a picker locates a particularly fruitful tree, they can gather a pound in about an hour. Rumors circulated that in more remote areas of New Mexico, piñon was selling for as much as $40 per pound to end customers. Thus, the income generated from harvesting can be crucial for families in the region. According to 2019 census data, 79 percent of McKinley County residents (which includes Gallup) were Native American, primarily from the southeastern part of the Navajo Nation and the entirety of the Zuni Pueblo to the south. The median household income was approximately $33,000, with 30 percent of residents living below the poverty line—12 percent higher than the state average. For these families, harvesting and selling piñon transcends tradition; it serves as an essential financial lifeline.

Jesica Adeky, a member of the Navajo Nation, gathers piñon with her family every year.

Jesica Adeky, a member of the Navajo Nation, gathers piñon with her family every year.“It’s like a seasonal job—one of my family members picks piñon during the summer, and with that money, they buy silver and stones to craft jewelry in the winter,” shares Jesica Adeky, a local from the Checkerboard area along Highway 602. Living in Bread Springs, New Mexico, her family land is about 20 minutes south of Ellis Tanner’s gallery and is part of the Navajo Nation. During the day, Adeky juggles two part-time roles as an office assistant for the Bááháálí (Bread Springs) Navajo Nation chapter house and at the public library in Gallup. If she can’t find time to pick piñon herself, she calls a family member to do it for her and pays them for their efforts.

As one moves away from piñon-rich areas like Gallup, the prices for raw piñon nuts increase for the pickers. Adeky has heard of pickers traveling as far as Flagstaff, three hours away, to sell their harvest to buying middlemen. Typically, venturing out of the densely populated piñon areas into drier regions gives sellers a chance to earn more on their sales. However, many pickers prefer same-day cash. As these middlemen, such as Ellis Tanner, resell the nuts, the retail price per pound can rise dramatically by the time it reaches the final consumer.

The business of brokering piñon has changed significantly, Tanner notes. “During my time in the trade, it feels like everything has declined. You aim to pass down something better to the next generation. But with piñons, the bark beetles have devastated the trees. We’re dealing with only about 10 percent of what we managed in the 1960s. That’s all that’s left.” Tanner recalls a time in the 1960s when he purchased as much as a million pounds of piñon and distributed it nationwide. In 2020, even with a bountiful harvest, he only bought around 80,000 pounds of nuts.

Tanner openly acknowledges that most of his piñon sales are made to national wholesale buyers. While he does sell some products through his trading post, all piñon undergoes a similar initial process. During peak season, Tanner purchases piñon by the pound from local harvesters. He then washes and cures the nuts to prevent spoilage (his specific curing method remains a closely guarded secret). Once cleaned and cured, the nuts are stored in a ventilated area until the next wholesale buyer arrives. That buyer then seasons, shells, or modifies the piñon to their preferences before it reaches the final consumer or is traded among various middlemen as it travels to distant markets.

A scale in Ellis Tanner’s shop is specifically used for weighing piñon, although he mentions that the market is lower compared to past years.

A scale in Ellis Tanner’s shop is specifically used for weighing piñon, although he mentions that the market is lower compared to past years. Piñon must be shucked by hand, making it a labor-intensive task.

Piñon must be shucked by hand, making it a labor-intensive task.Despite the high retail prices for piñon and the decent earnings per pound for pickers, Tanner points out that trading piñon doesn’t always yield significant profits for the effort involved in drying, curing, and cleaning the nuts. “If we achieve a 20-25 percent profit margin per pound, that’s a home run for us. Most of the time, it’s closer to a 10 percent margin.”

When Tanner sells the piñon he processes directly at his retail shop, he can easily double the price he paid for the nuts. However, the bulk of his sales don’t come from retail; he only sells about 5 percent of what he purchases, despite the community's fondness for it. He longs for the booming days of piñon trading, saying, “I wish I could buy in the old volumes. The main reason is the financial benefit it would bring to the Navajo people.”

While the trade of piñon may not be as profitable as it once was, Tanner remains optimistic about the economic prospects for local pickers who can sell their piñon directly at retail, bypassing middlemen like himself. “I’m here if you need me,” he says.

People have various ways of reaching the rich piñon forests of Bread Springs to gather nuts. Some stop along Highway 602 after hearing rumors that piñon has dropped, while others wander until they notice parked cars and then search for nearby trees. Many, like Adeky, have grown up in fertile areas where piñon is just steps away, making the annual gathering feel like picking up candy left on the doorstep.

“My earliest memory of piñon is my grandmother shelling it by hand for me when I was around 5 or 6,” Adeky recalls with a smile. “I would go with her to herd sheep, and we’d take piñon along for the long drives.”

To speed up the labor-intensive process of gathering piñon from the ground, modern harvesters have adopted several controversial methods. One technique involves picking entire sticky pine cones from the tree to knock loose the nuts still clinging inside. Another method consists of laying blankets on the ground, gripping the trunk of a piñon tree, and shaking it to dislodge the nuts from the cones without directly handling them. “For us Navajos, it’s traditionally believed that shaking the trees invites bears — it’s considered a bad omen,” explains Colina Yazzie, owner of Yazzie’s Indian Art in downtown Gallup.

Yazzie resides in Pinehaven, New Mexico, roughly seven miles from Bread Springs on the Checkerboard. Her role as a Native American jewelry broker takes her frequently from Gallup to Sedona, Phoenix, and Santa Fe, but she has a special affection for local piñon. “They taste like fresh milk. They’re incredibly rich.” To prepare freshly foraged piñon, Yazzie insists on a careful roasting method. “You wash the piñon, and while they’re still damp, you place them in a pan over medium heat, stirring until you can smell their aroma. When one pops, it’s time to take them off.”

In the fall of 2020, Yazzie took a creative leap by picking, roasting, and packaging her own piñon to sell alongside her jewelry and crafts. “Most of my piñon customers are Navajos — we truly cherish piñon.” She also views it as a way to connect loved ones with their home. “My sister lives in Austin, and I send her piñon as a gift since she can’t find it there.”

During a warm moment in her gallery, I ask Yazzie if she’s considering expanding her piñon brokering business — buying from pickers, roasting, and reselling. “I would, but just enough to roast for my store. I simply don’t have the space to store them or the strength to move them around.”

Colina Yazzie gathers piñon alongside her dogs; while she sells some, her true joy comes from savoring them herself.

Colina Yazzie gathers piñon alongside her dogs; while she sells some, her true joy comes from savoring them herself.Adeky describes the act of picking piñon as straddling the realms of hobby, tradition, and community. 'It’s a way to reunite your family. It provides a reason to ask for help; it embodies generosity and sharing with others.'

On a breezy Sunday last spring, I joined Adeky in a chain restaurant in Gallup, one of the few open establishments in the area. In the distance, the sturdy piñons remained largely closed, holding out for the right moment to release their fruits. As spring melted into a sweltering summer, Adeky patiently anticipated the chance to forage piñon near her home. However, as August turned to September and the cooler fall weather arrived, little piñon had been discovered on the Checkerboard. Although Adeky has a reserve from the fruitful 2020 harvest, the scarcity of piñon raises concerns about how bark beetles and heat waves will affect future yields in the region. This uncertainty also puts the financial stability of many locals, who depend on the seasonal income from abundant piñon drops, at risk.

Yet the cycle of boom and bust is a fundamental lesson about piñon, Adeky notes. 'From a young age, you learn that certain things happen in their own seasons,' she explains. 'It’s a form of education. During summer, you prepare for enough food to last through winter. At heart, people understand this. I hope they gather not only for profit but to recognize that there is a time of abundance.”

Karen Fischer is a writer residing in New Mexico.Adria Malcolm is a photojournalist and cinematographer from Albuquerque, NM, dedicated to long-term immersive storytelling.

1

2

3

4

5

Evaluation :

5/5