India’s high-speed rail ambitions are advancing, but progress remains slow despite significant investments.

From Mumbai’s crowded suburban trains to the overnight express mail services that operate like mobile cities, and the enchanting Darjeeling Himalayan ‘Toy Train,’ railways have become an iconic part of India’s identity.

It’s hard to imagine India’s rise to economic power without the crucial role railways have played in connecting people, goods, and industries across the vast nation.

Yet, as India’s economy grows, its rail system is facing mounting demands for faster travel times and greater freight capacity to keep pace with the needs of expanding industries.

While India’s traditional railway infrastructure has served it well for decades, much of it hails from the British colonial era and is now outdated, particularly when compared to the rapid rail advancements of its regional competitor, China.

The Indian Railways network caters to every segment of society, connecting even the smallest villages to some of the world’s busiest urban centers, all while balancing a complex array of needs to keep the nation moving.

With a total track length of 126,510 kilometers (78,610 miles), India’s rail network ranks as the fourth largest globally. It operates 19,000 trains daily and serves nearly 8,000 stations, with a fleet of more than 12,700 locomotives, 76,000 passenger coaches, and nearly three million freight wagons.

According to railway historian Christian Wolmar, ‘Few nations are as closely tied to their railways as India, whose recent history is inextricably linked to the growth of its vast rail system,’ as noted in his book *Railways and The Raj*.

The idea of railways in India was proposed as early as 1832, just seven years after the world’s first public railway, England’s Stockton & Darlington, began operations.

It wasn’t until April 1853 that the first stretch of the Great Indian Peninsular Railway began carrying passengers, connecting Bombay (now Mumbai) to Thane. India’s first high-speed passenger rail will revive this route when the Mumbai-Ahmedabad bullet train line opens later this decade.

‘Though the British primarily developed India’s railways for military use, the Indian population embraced them like no other, leading to an enormous demand and rapid expansion in the late 19th century,’ says historian Christian Wolmar.

‘Whether for business, family visits, pilgrimage, or daily commuting, this overwhelming demand made the railways highly profitable, helping them reach even the remotest corners of India far sooner than many other nations,’ adds Wolmar.

‘Although not initially built to serve the Indian population, the railways unintentionally sparked a transformation that continues to fuel the country’s growth in the 21st century,’ Wolmar concludes.

Slow speeds, yet lofty ambitions

In the 2019-2020 period, Indian Railways (IR) transported over 8 billion passengers and moved 1.2 billion tonnes of freight. As the nation’s largest employer, it also ranks as one of the world’s biggest non-military organizations, with a workforce of 1.4 million.

In terms of railway employment, only China Railway, with its 2 million workers, surpasses India’s rail workforce.

In comparison to the rail systems of Europe, China, Japan, or Korea, India’s average train speeds are still relatively sluggish. While some express trains can reach 160 kph (100 mph) or a bit higher, the national average for long-distance expresses is only 50 kph (31.4 mph), and regular passenger and commuter trains often struggle to exceed 32 kph (20 mph).

Freight trains are not much faster, averaging around 24 kph (15 mph), with a maximum speed ranging from just 55-75 kph. Without additional capacity, congestion is expected to worsen over the next three decades.

Currently, seven key routes make up 16% of the total rail network but carry 41% of all traffic. About a quarter of Indian Railways’ network operates at between 100% and 150% of its intended capacity, leading to widespread disruptions when any delays occur.

India’s ambitious plan? To introduce high-speed rail links between major cities, build thousands of kilometers of dedicated freight corridors (DFCs) for cargo, and complete the electrification of the entire network by 2024.

It’s a monumental goal, but the first DFCs are already in use, and electrification is progressing quickly. Three additional DFCs, covering 5,750 kilometers, are set to further expand the system, with two new routes expected to finish this year.

High-speed ambitions

Much like Japan and China, India sees high-speed rail as a vital tool for cutting travel times, increasing capacity, and boosting economic growth.

In 2021, India unveiled an ambitious National Rail Plan, aiming to link all major cities in the north, west, and south via high-speed rail. Priority is being given to cities between 300 and 700 kilometers apart, with populations of over one million.

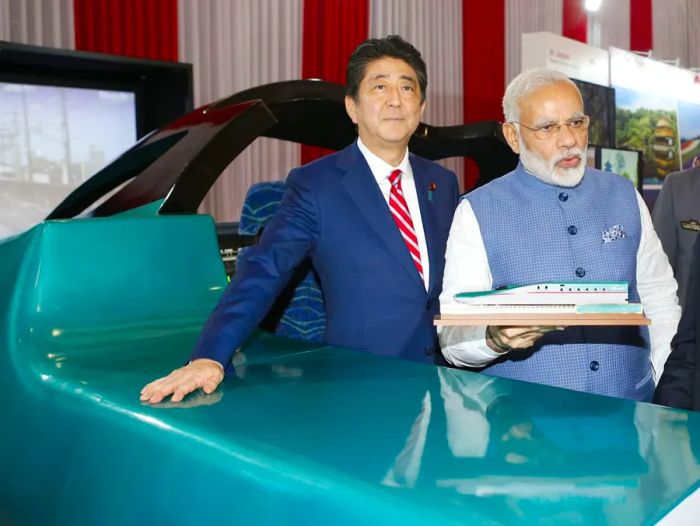

India has turned to Japanese expertise, technology, and financing to help build its first high-speed rail line, a 508-kilometer route connecting Mumbai and Ahmedabad in western India.

In the coming decades, a further 12 routes could be added to India’s high-speed rail network if all current proposals are realized.

The National High-Speed Rail Corporation Ltd (NHSRCL), responsible for financing, building, and managing India’s bullet train projects, has received approval for eight new high-speed rail corridors connecting cities like New Delhi, Varanasi (958 km), Lucknow-Ayodhya (123 km), Mumbai-Nagpur (736 km), New Delhi-Ahmedabad (886 km), New Delhi-Amritsar (480 km), Mumbai-Hyderabad (711 km), and Varanasi-Howrah (760 km).

In early 2022, four additional corridors were proposed, bringing the total to over 8,000 kilometers. If approved, new routes could link Hyderabad and Bangalore (618 km), Nagpur-Varanasi (855 km), Patna-Guwahati (850 km), and Amritsar-Pathankot-Jammu (190 km), positioning India’s network as the second largest high-speed rail system globally.

When the Mumbai-Ahmedabad project was first announced by Prime Ministers Narendra Modi and Shinzo Abe in 2017, the goal was to have bullet trains running by the 75th anniversary of India’s independence on August 15, 2022. However, delays and various challenges have pushed the expected completion date to at least 2028.

Disagreements over the route and protests from farmers and regional politicians concerned about the loss of agricultural land have led to significant delays in land acquisition and route surveys in Maharashtra. Echoing the widespread opposition to high-speed rail seen in other nations, including the UK, Chief Minister Uddhav Thackeray questioned the value of the project, dismissing it as a ‘white elephant.’

By September 2021, only 30% of the necessary land in Maharashtra had been acquired, in stark contrast to Gujarat, where 97% of land had been secured, and other regions where acquisition was completed.

‘The question has always been, ‘Why not improve the current infrastructure and run faster trains on it?’ says Rajendra B. Aklekar, author and Indian railways expert.

Indian Railways has already launched an initiative to increase speeds on existing corridors to 160 kph by upgrading both tracks and signaling. Additionally, a nationwide dedicated freight network is under development to separate freight traffic from passenger services and reduce congestion on major routes.

Dinogo reached out to Indian Railways for a statement regarding its National Rail Plan but did not receive a reply.

Elevated viaducts

A 21-kilometer stretch north of Mumbai will be underground, featuring a seven-kilometer undersea tunnel.

Eleven elevated stations will be built along the line, serving key cities such as Thane, Virar, Boisar, Vapi, Bilimora, Surat, Bharuch, Vadodara, Anand, Ahmedabad, and Sabarmati. These stations will allow easy transfers to existing Indian Railways services.

Unlike other high-speed systems like the French TGV or Eurostar, India’s bullet trains won’t be able to operate on existing tracks. India’s railways have historically used a broader track gauge of 1,676 millimeters (5 feet 6 inches), while the new Japanese-built line will follow the global standard gauge of 1,435 millimeters.

‘Indian Railways operates a diverse range of services, catering to everyone from the poorest to the wealthiest, but the high-speed railway is being developed as a separate corridor with international standard gauge and a dedicated network, not integrated with the national lines,’ says Aklekar.

The Japanese-inspired 10-car trains, based on the E5 ‘bullet train,’ will reach speeds of up to 320 kph, reducing the journey time from the current seven hours to just over two hours for the fastest services.

‘This project is fundamentally about technology,’ concludes Aklekar.

‘India has to start somewhere, and that moment is now. Adopting and perfecting new technologies takes time. For instance, Japan’s Hokkaido Shinkansen took 42 years to be fully operational. If we don’t begin now, we risk falling behind,’ says Aklekar.

Despite the optimism, Indian Railways’ precarious financial situation casts a shadow over the project. In the past six years, costs have been rising more than twice as fast as revenues, while productivity continues to decline.

A recent wage hike for staff has further strained the financials, with pension contributions now consuming a staggering 71% of operating expenses. Although staff numbers are decreasing, a new recruitment drive aims to bring in 140,000 more employees by June.

In 2014, then-Railway Minister Sadananda Gowda expressed frustration, stating that IR ‘is expected to generate commercial profits but operate as a welfare organization,’ pointing to financial losses due to low passenger fares.

High-profile projects like the Dedicated Freight Corridors, major station upgrades, logistics parks, and the launch of new passenger trains have all stalled, while Indian Railways continues to lose ground in both the freight and passenger sectors.

While IR’s challenges with rising costs, congestion, and the need for significant investments in infrastructure are not unique, the magnitude of these issues is more pronounced than in most other countries.

The Indian government will be eager to see its flagship rail initiatives completed and delivering their promised benefits, not just to aid economic recovery, but also to demonstrate to its competitors that it can provide world-class 21st-century transportation.

1

2

3

4

5

Evaluation :

5/5