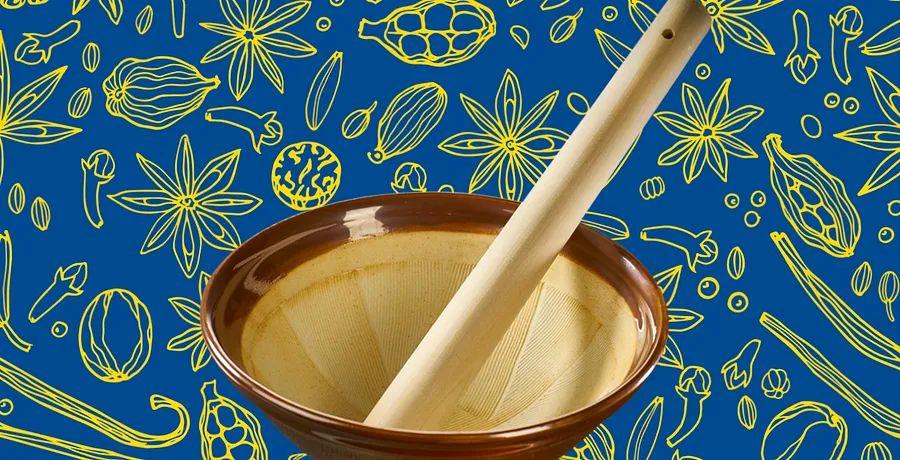

Japan Perfected the Mortar and Pestle with Suribachi and Surikogi

When I received my suribachi and surikogi, I felt apprehensive. My parents rarely used a mortar and pestle, leaving me unfamiliar with the ceramic bowl's intricate ridges and the wooden muddler. However, seeking to connect with my roots and tackle more complex recipes, I embraced this traditional pair as an adult, and now I rely on them nearly every day.

Almost every culture boasts its own version of the mortar and pestle, crafted from locally sourced materials like wood, marble, or volcanic rock, tailored for traditional cuisines. The Japanese suribachi, however, is a blend of various cultural influences. Its fundamental design was introduced to Japan by Chinese traders in the 11th century, alongside traditional Kampo medicine, possibly utilized by Buddhist monks for grinding herbal remedies. In the 16th century, after Japan’s invasion of Korea, Korean techniques influenced Japanese ceramics, shaping the classic suribachi style: glazed on the exterior and unglazed on the interior. This history is evident in modern applications, such as grinding sesame seeds, which Japan imports extensively, second only to China, having been brought from India with Buddhism for both medicinal and spiritual uses.

Grinding sesame seeds can be challenging; they're fragile and can scatter if nudged. A tool specifically designed to contain and crush ingredients without damaging them is essential. While mortars and pestles are ubiquitous, the Japanese version is distinctive due to its internal grooves that effectively break down ingredients, complemented by a lightweight wooden pestle that's easy to handle, enabling users to extract maximum flavor through clever design rather than advanced technology.

Reasons to own one

In a modern American kitchen, when a recipe calls for ground ingredients, you might be tempted to reach for a Nutribullet. However, using blades to crush seeds and spices doesn’t effectively release the flavors that recipes depend on. Blades chop ingredients without necessarily extracting their essential oils or flavors. Utilizing a suribachi to break down these components is the gentlest method to handle delicate herbs and intensely flavored seeds, and it’s simpler than you may think.

The suribachi and surikogi have become essential tools in Japanese kitchens because they perform efficiently. Timing is crucial in Japanese cooking, as chefs carefully layer flavors such as salt, sugar, soy sauce, vinegar, and miso into their dishes. There's little time to struggle with a cumbersome mortar and pestle.

If you’ve previously used granite pestles, you may be surprised by how little pressure is required with a suribachi; you'll quickly discover that the grooves assist in the grinding process, reducing the physical effort and speeding things up. The grooves also create enough texture for a satisfying mouthfeel, while their intricate pattern helps guide ingredients back to the bowl's center as you grind, preventing them from escaping. The surikogi is equally optimized, featuring a lightweight wooden handle traditionally crafted from sansho pepper tree branches, believed to possess purifying qualities by Japanese herbalists.

The suribachi excels with both wet and dry mixtures. To make nerigoma, a Japanese sesame paste akin to tahini, simply grind toasted sesame seeds and gradually incorporate sesame oil to achieve your desired consistency. Other Japanese dishes such as shiraae (mashed tofu salad) and tsukune and tsumire (meatballs and fish balls) can also be prepared in this mortar. Beyond Japanese cuisine, the suribachi and surikogi are perfect for muddling herbs for cocktails, creating curry pastes, mashing avocado for toast, or emulsifying aioli.

Some manufacturers in Japan have been crafting suribachi for centuries, drawing on various clay traditions like Mino and Iwami pottery, and they’ve mastered the art of sourcing clay and firing their bowls. The natural composition of clay used in traditional pottery allows an old-school suribachi to resist water, enhancing its durability over time. (Newer suribachi are also fine, though their clay and glaze quality might not match that of the older ones.)

Suribachi bowls come in various sizes depending on the source, yet even the larger options remain quite lightweight. Like many Japanese ceramic tools, suribachi are often visually stunning, making them suitable for use as serving dishes as well.

How to use it

Depending on your recipe, you might want to begin by toasting your ingredients to enhance their flavor, particularly when adding nuts or seeds to salads, fried tofu, or rice. Once your ingredients are in the bowl, move the surikogi in a circular motion, almost like cleaning the inside surface. Apply pressure, but not excessively. If you're stirring in oil for a dressing, aioli, or nerigoma, add it gradually while emulsifying with the surikogi. Since the suribachi is made of clay, be cautious about using heavier utensils instead of the surikogi, as they could damage the grooves. When ready to serve, use a plastic spatula to transfer your crushed ingredients or sauce, or serve directly from the bowl.

For cleaning, brush out any residue from the grooves using a cooking brush. Rinse with water and a bit of soap if necessary, then dry the inside and the surikogi with a towel before storing them immediately. While some models may be dishwasher-safe, they typically don’t get dirty enough to warrant such heavy cleaning, and you should be mindful of the material quality.

Where to find one

Many Japanese stores offer international shipping. I recommend Jinen, which specializes in suribachi crafted in the Iwami style. MTC Kitchen also provides a variety of Japanese cooking essentials, including budget-friendly suribachi.

Japanese Suribachi

- $24

Prices listed are current as of publishing.

- $24 available at Jinen

Ray Levy Uyeda is a writer based in the Bay Area.

1

2

3

4

5

Evaluation :

5/5