Khao San Road in Bangkok transformed from a bustling rice market into the world's most renowned travel destination.

In the past, locals on Khao San Road were known for selling an abundance of rice.

Barge after barge, initially rowed by hand and later powered by engines, navigated the Chao Phraya River, delivering thousands of tons of rice in jute sacks to local wholesalers along Banglamphu Canal.

By the end of the 1800s, the Banglamphu area had become the largest rice market in Bangkok and the entire Kingdom of Siam, the world’s top rice producer at the time.

Smaller vendors started setting up shop south of the canal, where a dirt path became so congested with rice trade that in 1892, King Chulalongkorn ordered the construction of a proper road. Measuring only 410 meters, it wasn't grand enough to be named after a national figure, so it was simply called Soi Khao San (Milled Rice Lane).

As Banglamphu grew wealthy from rice trade, it expanded into various industries, including Thailand’s first ready-made school uniforms, buffalo-leather footwear, jewelry, gold leaf, and costumes for traditional Thai dance. The local thirst for entertainment led to the creation of two musical comedy venues, the nation's first record label (Kratai), and one of Siam's earliest silent-film theaters.

However, just a century later, an influx of international backpackers nearly overshadowed the local market scene. What began as a trickle in the 1970s, when Bangkok was the final stop on the Asian hippie trail, surged into a massive flood of travelers by the 1990s.

Guesthouses began to appear in abundance.

It’s hard to imagine anyone foreseeing the inevitable transformation of the street and the surrounding area.

When I first walked down Khao San Road 40 years ago for a research trip for the inaugural Lonely Planet Thailand guide, the street was lined with two-story shophouses from the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

On the ground level, there were rows of shoe shops, traditional Thai-Chinese coffee houses, noodle stalls, grocery stores, and motorcycle repair shops, with shopkeepers and tenants residing above.

A handful of rice dealers remained, but as 10-wheel trucks replaced the river barges, the rice trade and transportation largely moved to other areas.

While Yaowarat (Bangkok's Chinatown) was the commercial hub for Chinese businesses and residents, and Phahurat served the Indian community, Banglamphu remained distinctly Thai. Nearby, along Chakkaphong and Phra Sumen Roads, artisans still crafted costumes and masks for traditional Thai dance performances.

After a long, sweltering day spent taking notes on iconic landmarks like the Grand Palace, Wat Phra Kaew (Temple of the Emerald Buddha), Wat Pho (Temple of the Reclining Buddha), and the Giant Swing—each within a kilometer of Khao San Road—I was ready to call it a day.

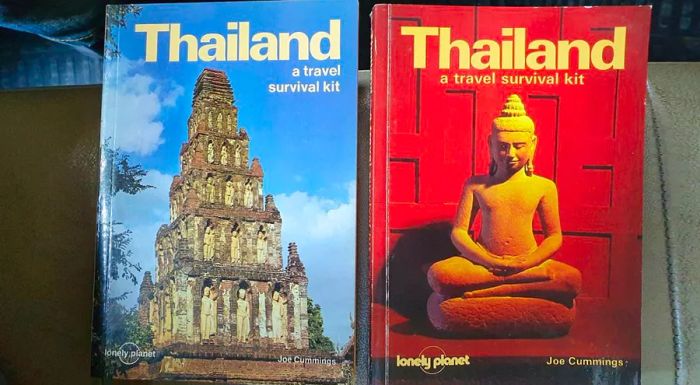

The only accommodations listed on Khao San Road in the first edition of 'Thailand: A Travel Survival Kit,' published in 1982, were two hotels and three guesthouses.

When I returned a year later to update the guide, five more guesthouses had popped up on or near Khao San, which I added to the second edition in 1984.

From then on, every time I visited Banglamphu for the biannual updates, the number of places to stay seemed to grow exponentially. Within just ten years, the options stretched block by block from Khao San Road to neighboring streets and alleys, with backpacker hostels and guesthouses eventually surpassing 200.

The 'Beach' effect.

By the mid-1990s, Khao San Road had become a global sensation, standing as the largest backpacker hub of the 'three Ks'—Kathmandu, Khao San, and Kuta Beach. Not only did it cater to the world’s largest transient backpacker population, but Khao San also became notorious for its thriving black market in unlicensed music, counterfeit books, fake IDs, and knockoff luggage.

Numerous bucket shops emerged, offering unbeatable deals on obscure airlines flying offbeat routes to almost every airport worldwide.

Alex Garland, then an unknown author (now renowned for directing sci-fi films like 'Ex Machina' and 'Annihilation'), further cemented Khao San Road’s wild reputation with his 1996 cult novel 'The Beach.' The first seven chapters take place on Khao San, where Richard, a young English traveler, meets a quirky Scotsman named Daffy Duck, who hands him a secret map to a mysterious 'beach.'

The novel paints a vivid picture of a typical guesthouse room on Khao San Road: 'One wall was concrete—the side of the building. The others were just bare Formica. They wobbled when I touched them. I felt as though if I leaned against one, it might topple over and knock the others down like a set of dominoes. Just below the ceiling, the walls stopped, and a strip of metal mosquito netting filled the gap.'

In 2000, a film adaptation directed by Danny Boyle and starring Leonardo DiCaprio introduced Khao San Road to a much larger global audience, likely surpassing both the novel and my Lonely Planet guides in fame.

That same year, Italian electronic music producer Spiller released the video for his dance track 'Groovejet (If This Ain’t Love),' which featured a memorable scene filmed in an underground Khao San Road nightclub, where Spiller and singer Sophie Ellis-Bextor danced.

A 2000 New Yorker article referred to Khao San Road as 'the travel hub for half the world, a place that thrives on the desire to be somewhere else,' describing it as 'the safest, easiest, and most Westernized place to start a journey through Asia.'

Khao San Road today.

According to the Khao San Business Association, the road attracted an impressive 40,000-50,000 tourists daily during the high season in 2018, and 20,000 visitors per day in the low season.

The project, partly aimed at improving Khao San's reputation, was scheduled for completion by late 2020. It included repaving the road, upgrading footpaths, and installing retractable bollards to designate spaces for 250–350 licensed Thai vendors, chosen through a lottery.

Vehicles were set to be prohibited from the road between 9 a.m. and 9 p.m. every day.

When Thailand shut its borders in April 2020 due to the coronavirus pandemic, international tourist arrivals dropped to zero nearly overnight. However, Khao San Road began to see a partial recovery when domestic travel resumed in July. By the time the renovated Khao San opened in November 2020, weekends found the road filled with Thai youth, along with a smaller number of expatriates.

Pubs along the street, which once catered to 80% European clientele, now saw nearly 90% of their customers as Thai nationals.

In November, a vibrant 10-day light installation event called Khao San Hide and Seek attracted a steady stream of visitors. The installations were complemented by live performances from nearly 20 bands. Local studios held workshops showcasing traditional Banglamphu arts, including the crafting of khon (classical Thai dance-drama) costumes, preparing khaotom nam woon (sticky rice triangles wrapped in fragrant pandanus leaves), and carving thaeng yuak (intricate patterns on fresh banana tree trunks used in Buddhist ceremonies).

The neighborhood faced another blow when a second wave of COVID-19 cases surged in early January 2021. The government quickly ordered the closure of all entertainment venues in Bangkok, causing Khao San Road to empty once again.

Later that month, I revisited the nearly empty Khao San Road and stopped by VS Guesthouse, the first and oldest guesthouse still standing. Every other guesthouse in the area was closed, but to my surprise, the vintage wooden doors of VS were wide open.

I spoke with the family members who have owned the house for four generations. Rintipa Detkajon, the older of two sisters who now manage the home, fondly remembered how her late father, Vongsavat, began hosting foreigners in the early 1980s, offering them a place to sleep on the family’s living room floor.

'I was about 16 when our first guest, an Australian man, stayed with us,' she recalled. 'Back then, foreign travelers were much quieter. They were interested in history and culture, unlike today’s travelers who seem more focused on partying and drinking.'

I asked Rintipa how the pandemic had impacted their business.

'It’s not just us, it’s the whole world,' she said. 'We’re all going through this together. This is our home, so we’ll get through it.'

Evaluation :

5/5