One of the World's Most Remote Islands Revitalized Its Culture and Traditions During a 2-Year Pandemic Closure — Now Attracting Travelers Once Again

Majestic moai watch over Ahu Tongariki on the Chilean island of Rapa Nui.

Photo: Rose Marie Cromwell

Majestic moai watch over Ahu Tongariki on the Chilean island of Rapa Nui.

Photo: Rose Marie CromwellAs I witnessed the moai for the first time at sunset, they loomed over the coast of Easter Island, or Rapa Nui, resembling colossal warriors cloaked in gold. Averaging 13 feet tall and weighing up to 14 tons, these extraordinary figures took on a more human-like appearance as I approached. One had wide eyes, another bore a stern expression, while a nearby figure on the hill appeared quite charming.

This Chilean territory is home to nearly 1,000 moai (meaning “statues” in Rapanui). Believed to have been carved between the 12th and 17th centuries, these statues were created after Polynesians navigated to the center of the world’s largest ocean, discovering a lush, uninhabited island. However, production ceased in the 18th and 19th centuries due to enslavement by Peruvian raiders, increasing civil strife, and disease. By the early 2000s, the moai had generated a $120 million tourism industry, attracting over 150,000 visitors annually from around the globe.

From left: Vibrant pink hibiscus, which thrives on the island; performers reenacting the carving of moai at Te Moana restaurant in Hanga Roa.

Photo: Rose Marie Cromwell

From left: Vibrant pink hibiscus, which thrives on the island; performers reenacting the carving of moai at Te Moana restaurant in Hanga Roa.

Photo: Rose Marie CromwellThen, in March 2020, everything came to a halt. Concerned that the island’s only hospital, equipped with just three ventilators, was unprepared for the pandemic, Mayor Pedro Edmunds Paoa requested that LATAM Airlines suspend all flights to Mataveri International Airport, the world’s most isolated commercial airfield. This move effectively severed the island's connection to the outside world, reminiscent of the late 1960s when the first propeller planes flew from Santiago across the South Pacific. At that time, 72 percent of the island's 7,750 residents relied on tourism for their livelihoods. Suddenly, not only did visitors vanish, but essential supplies became scarce.

The lounge at Nayara Hangaroa, featuring stunning views of the Pacific Ocean.

Photo: Rose Marie Cromwell

The lounge at Nayara Hangaroa, featuring stunning views of the Pacific Ocean.

Photo: Rose Marie CromwellWhat transpired next? Paoa urged the entire community to observe tapu, a traditional Polynesian practice of imposing restrictions on places or objects (this concept is believed to have inspired the word taboo). Restaurants, hotels, and gathering spaces shut their doors. The local government also encouraged islanders to embrace the principle of umanga, or solidarity, sharing labor, food, and goods with their neighbors selflessly. Citizens donated old clothing, assisted each other in planting crops, and took turns visiting the elderly. For 28 months, residents revitalized the traditions that had been swiftly fading from their lives.

After nearly 2.5 years of complete isolation, the territory finally lifted its self-imposed restrictions. A few months later, my flight was among the first to return to Rapa Nui.

My initial destination was Nayara Hangaroa, a lush 18-acre resort on the southwestern tip of the island, which spans just 14 miles. Speaking with the receptionist, I felt a wave of excitement about this new chapter for visitors, and I was eager to be part of it. The staff welcomed me with a fragrant frangipani garland, offered a refreshing pisco sour, and then guided me to a spacious villa with stunning views of the coastline.

From left: Pianist Mahani Teave performs at the Rapa Nui School of Music & the Arts; fresh island-grown bananas at a Hanga Roa market.

Photo: Rose Marie Cromwell

From left: Pianist Mahani Teave performs at the Rapa Nui School of Music & the Arts; fresh island-grown bananas at a Hanga Roa market.

Photo: Rose Marie CromwellI had visited Rapa Nui twice before the pandemic, but this time felt unique. Thanks to a beautification project during COVID, the island was adorned with newly planted flowering trees, and its vibrancy was evident in more subtle ways. Artists had been commissioned to create intricate wooden street signs to hang among the palms and bougainvillea in Hanga Roa, the island’s capital and sole town. Through government-supported work programs, unemployed scuba instructors collected 10 tons of debris from the coastal seabed, while hiking guides removed another 10 tons from the shore.

Nayara Hangaroa emerged as a positive outcome of the pandemic. Previously known as the Hangaroa Eco Village & Spa, it was rebranded as a Nayara resort after the island closed in 2020. The new ownership revamped the rooms and established a clearly marked walking path on the grounds; guest experiences now include interactions with local artists and musicians.

From left: A moai statue graces the grassy plains of eastern Rapa Nui; indigenous iconography decorates Santa Cruz Catholic Church.

Photo: Rose Marie Cromwell

From left: A moai statue graces the grassy plains of eastern Rapa Nui; indigenous iconography decorates Santa Cruz Catholic Church.

Photo: Rose Marie CromwellI discovered that the design of my villa—a circular structure made from volcanic stone, topped with a lush carpet of grass—was inspired by Orongo village, a significant archaeological site on the island. The following day, I embarked on a 15-minute drive to the site, located along the edge of the Rano Kau volcanic crater. From the late 17th to the mid-19th centuries, Orongo hosted the Tangata Manu, or “birdman” competition. As part of this annual tradition, men would scale the volcano’s 1,000-foot cliffs and swim to a nearby islet, racing to be the first to return with the egg of a migratory bird, the sooty tern. The winner's clan leader would then reign over the island for the coming year.

Today, Orongo is beautifully preserved, featuring round houses with stone walls and grass roofs designed to keep the interiors cool—just like my villa. At the village's edge, I discovered petroglyphs depicting half-man, half-bird figures carved into the basalt cliff, narrating the story of this ancient ritual.

Rapa Nui stands as one of the most remote locations on the planet. Its closest inhabited neighbor, the British territory of Pitcairn Island, lies about 1,200 miles to the west and hosts only around 50 residents. From Rapa Nui, one must journey nearly 2,200 miles east to reach mainland Chile. Perhaps this isolation is why locals perceive the sea not as a barrier, but as a highway that unites them.

On my third morning at Nayara, I rose early with the anticipation of hiking up Ma‘unga Terevaka, the highest point on Rapa Nui at 1,673 feet. This volcano, along with two others, formed the island's triangular shape over 100,000 years ago. It is said that atop this peak, Rapanui elders taught their children to read the night skies, an essential skill for navigating the seas.

An Explora guide leading the way to the now-extinct Poike Volcano, one of the three volcanoes that shaped Rapa Nui.

Photo: Rose Marie Cromwell

An Explora guide leading the way to the now-extinct Poike Volcano, one of the three volcanoes that shaped Rapa Nui.

Photo: Rose Marie CromwellFrom the breezy peak, the vast Pacific Ocean stretched out in every direction. The cobalt-blue water sparkled under the sun, appearing to blend seamlessly with the low-hanging clouds. As I stood there beside my guide, Alberto “Tiko” Te Ara-Hiva Rapu Alarcon, I felt as if I could glimpse the curve of the earth itself.

'You had to be resilient to come here and thrive in such a remote location,' remarked Alarcon, whose tattoos tell stories of his heritage and who also performs as a Polynesian dancer. 'When you gaze at an empty horizon,' he added, 'it can evoke a profound sense of solitude.'

The entrance to Explora Rapa Nui.

Photo: Rose Marie Cromwell

The entrance to Explora Rapa Nui.

Photo: Rose Marie CromwellWhile the base of this long-dormant volcano boasts the island's most fertile soil, farmland transitioned to development when locals shifted from agriculture to tourism in the late 1990s. Thus, I was taken aback when Alarcon and I descended Terevaka to find newly planted fields of pineapples, bananas, sweet potatoes, and taro. On our return to Nayara, we spotted numerous family gardens. Along Hanga Roa's main street, Atamu Tekena, I noticed half a dozen vendors offering fresh produce.

During my last visit to the island in 2017, vegetable shipments from mainland Chile were infrequent, and local supplies were minimal. Now, after 2.5 years of striving for self-sufficiency, islanders are thriving on produce from their own gardens, with about 1,300 new plots cultivated during the pandemic.

Souvenirs found in Hanga Roa.

Photo: Rose Marie Cromwell

Souvenirs found in Hanga Roa.

Photo: Rose Marie Cromwell'My mother used to have a stunning vegetable garden here,' Olga Elisa Icka Pacarati shared with me as I saw her harvesting radishes outside her home in Hanga Roa. 'Then she fell ill, and we stopped gardening until April 2020.' Pacarati received free training from a government initiative called proempleo to cultivate her small plot. With the mayor revitalizing the concept of umanga, she donates 40 percent of her harvest to a local food charity. The remainder often finds its way to nearby restaurants, proudly offering meals made with locally sourced ingredients.

That evening at Te Moai Sunset restaurant, I sampled tiradito, a sashimi-style dish of raw mahi-mahi drizzled with a spicy mango coulis. On another occasion, I visited Te Moana, where I enjoyed a refreshing cucumber and tuna ceviche served in a conch shell, accompanied by fried taro and a fluffy baked dessert called po‘e, made with coconuts and bananas.

Inside one of the 26 Varúа guest rooms at Explora Rapa Nui.

Photo: Rose Marie Cromwell

Inside one of the 26 Varúа guest rooms at Explora Rapa Nui.

Photo: Rose Marie CromwellHowever, my most enjoyable meals were at my second hotel, Explora Rapa Nui, an upscale 30-room establishment nestled in the island's interior. Upon my arrival, I relished a fresh green salad followed by sweet-potato gnocchi; the next day, I savored a lamb loin topped with a tangy pineapple chutney served over mashed taro. The three-course menus prominently featured freshly caught tuna, mahi-mahi, and swordfish, often served raw as ceviches, carpaccios, or tartares.

'Before the pandemic, over half of our ingredients were sourced from the mainland,' chef Marco Guzmán explained. 'Now, we're focusing on using 100 percent local produce, as there are more opportunities to collaborate with island suppliers.'

A horse grazes near Ahu Tahai on the island's west coast.

Photo: Rose Marie Cromwell

A horse grazes near Ahu Tahai on the island's west coast.

Photo: Rose Marie CromwellBetween meals, I joined Explora’s guides to explore the highlights of Rapa Nui National Park, which encompasses much of the island, including the moai. In early 2018, full management and conservation of the park were entrusted to the Ma‘u Henua Indigenous Community, established in 2016 in response to local calls for greater sovereignty over ancestral lands. Since then, the Ma‘u Henua have raised the cost of the 10-day entrance pass from $60 to $80 for foreign visitors, encouraging them to extend their stay from the typical three days to a full week. Additionally, the organization requires accredited local guides for all visitors to archaeological sites to safeguard the ruins.

For me, exploring the national park with a guide was transformative. At Anakena, the island’s primary beach, I learned the legend of chief Hotu Matu‘a, who is believed to have arrived — possibly as early as A.D. 300 — after a remarkable voyage spanning around 2,300 miles of open sea. (In 2021, the island reinstated a holiday to honor this journey.) I later visited the Rano Raraku volcanic crater with Explora guide Esteban Manu Reva, which served as the main quarry and workshop for the original Rapanui people when carving the massive figures. However, only a fraction of the nearly 1,000 moai crafted ever reached their stone platforms, or ahus. Nearly 400 remain unfinished, and approximately 92 broke during transport. Today, many can still be seen where they lay abandoned. Additionally, at least a dozen were removed from the island by academic “explorers” and are now displayed in museums, mainly in the U.S. and Europe.

Anakena Beach, located on Rapa Nui's northern coast.

Photo: Rose Marie Cromwell

Anakena Beach, located on Rapa Nui's northern coast.

Photo: Rose Marie CromwellThe method by which these colossal moai, each weighing as much as a couple of bull elephants, were positioned on their ahus remains a mystery. Rapanui oral traditions suggest that the moai “walked” to their platforms, while many scientists believe they were hoisted upright with ropes. I followed a trail that led to nine of the fallen statues, heading toward Ahu Tongariki, a stone platform nearly 700 feet long on the eastern coast of the island. Fifteen moai stand there, gazing inland with their backs turned to the ocean.

Remarkably, all the moai currently standing on Rapa Nui were toppled during interclan conflicts by the late 19th century, a period marked by population decline due to disease and slave raids. Government initiatives in the latter half of the 20th century aimed to restore the sacred carvings, but the stories of the violence have become woven into the island's cultural history.

Crops flourish in the rich soil of Rapa Nui’s interior.

Photo: Rose Marie Cromwell

Crops flourish in the rich soil of Rapa Nui’s interior.

Photo: Rose Marie Cromwell“Rapa Nui is often cited as a classic example of a society that self-destructed,” remarked classical pianist Mahani Teave when I met her at Toki Rapa Nui, an organization focused on teaching youth about cultural and environmental stewardship. “So I believe we should aim to transform it into an island that is completely self-sustainable,” she expressed.

Teave discovered her passion for music at the age of nine when a retired violinist brought the island's first piano. She was only eight months into her lessons when the musician returned to mainland Chile, taking the piano with her. Captivated by the instrument, Teave eventually left Rapa Nui, initially training in Valdivia, Chile, before moving on to the U.S. and Europe. Thirteen years ago, she returned with two pianos to establish the Rapa Nui School of Music & the Arts, which has since expanded to include ten more pianos. The school offers instruction in classical instruments (piano, violin, cello) and traditional music (ukulele and an ancestral singing style known as Re o Riu).

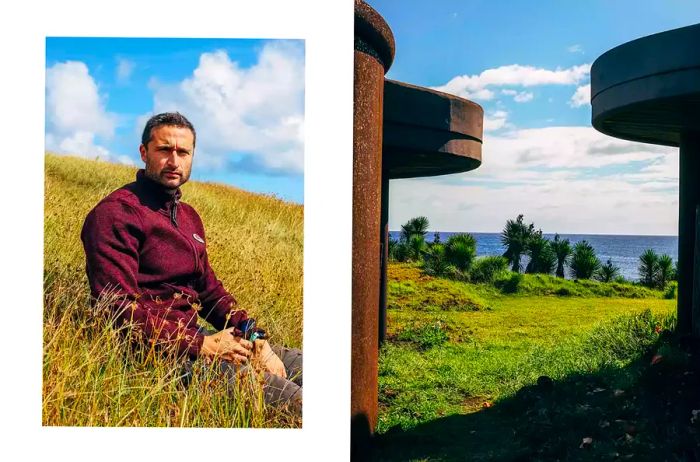

From left: Guide Alberto “Tiko” Te Ara-Hiva Rapu Alarcon leads cultural tours on Rapa Nui; a view of the eastern Pacific Ocean from Nayara Hangaroa, a 75-room resort.

Rose Marie Cromwell

From left: Guide Alberto “Tiko” Te Ara-Hiva Rapu Alarcon leads cultural tours on Rapa Nui; a view of the eastern Pacific Ocean from Nayara Hangaroa, a 75-room resort.

Rose Marie CromwellThe school operates within the Toki Rapa Nui center, a building designed in the eco-friendly Earthship style. This flower-shaped structure is constructed from upcycled materials, including 2,500 tires, 40,000 cans, 25,000 glass bottles, and 12 tons of recycled plastic. In addition to music classes, students can also learn traditional carving, cooking, and dancing.

At the center, children receive instruction in both Spanish and Rapanui, a language spoken by only 18 percent of islanders under 18. “We risk losing our language when it becomes merely a performance for visitors,” Teave remarked. “If we don’t understand what we’re singing — if we lose the stories behind our dances — the culture belongs to them, not to us.”

Later that evening, I understood her point as I attended a recital by Toki teachers at Mana, a gallery showcasing local artists. Performers glided onto the stage in elegant white gowns. Teave greeted the audience — composed entirely of island residents — in Rapanui, adorned with shells around her neck and ferns woven into a crown atop her head. The concert commenced with classical pieces by Bach and Brahms before transitioning into “Ko Tu‘u Koihu e,” a traditional Rapanui ballad. Vairoa Ika, cofounder of Toki and director of environmental initiatives on the island, was so moved that she jumped from her seat to dance on stage.

It felt as if the entire island had gathered, with some spectators even peering through open windows when there was no room left inside. Sitting in that gallery filled me with immense joy; it dawned on me that the musicians weren’t performing for outsiders; at last, they were playing for themselves.

On my final day, I met the affable Mayor Paoa in his palm-fringed office in Hanga Roa. I was curious about his thoughts on this pivotal moment in the island’s history. Was he feeling optimistic?

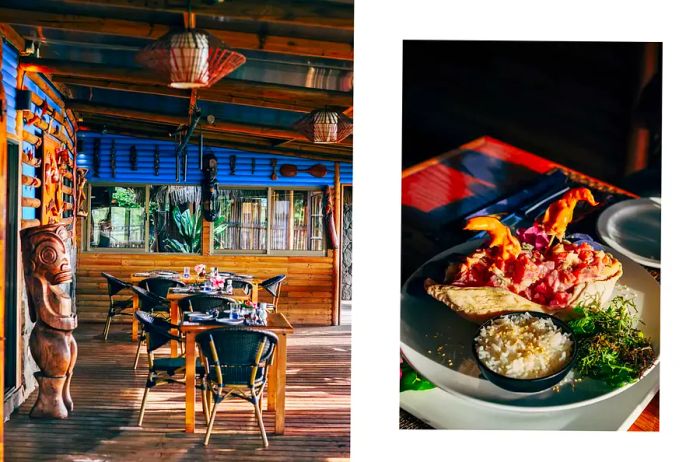

From left: The outdoor dining space at Te Moana; tuna ceviche served at Te Moana.

Rose Marie Cromwell

From left: The outdoor dining space at Te Moana; tuna ceviche served at Te Moana.

Rose Marie Cromwell“How can we reset our path for the future?” he pondered, offering me a sweet banana from his garden. “It begins with fostering a vision among the local community that every action you take today will yield results in twenty years.”

Paoa views the revival of agriculture, concepts like umanga, and Rapanui culture—supported by organizations such as Toki—as essential initial steps. For visitors, this reset may involve fewer flights and extended stays, along with more diverse, enriching experiences in areas like astronomy, scuba diving, and hiking. The aim is to discourage quick visits just for a selfie with a moai — at least, that’s the aspiration.

“I believe the pandemic served as a lesson for us to pause and reflect on how we treat our culture, our resources, and our sustainability efforts,” he stated. “Now we have an opportunity to reorganize and improve.”

Paoa compared uncontrolled tourism to a consuming obsession — one that had overwhelmed Rapa Nui before the pandemic. He hopes that other priorities, including cultural pride and strong agricultural practices, will redefine life on the island. The iconic moai will still attract visitors, but they will be seen as part of a broader, deeper narrative. Regardless of what the future brings, the moai will remain vigilant, observing what unfolds next.

Where to Stay

Explora Rapa Nui: A stay at this intimate lodge with just 30 rooms offers guided explorations with bilingual experts (who receive extensive training), meals made from local ingredients, and evening cocktails at the Explorer’s Bar.

Nayara Hangaroa: Featuring volcanic stone and cypress wood, this 75-room resort invites guests to discover the island through hiking, mountain biking, and ATV rides, or to unwind at the Manavai Spa.

Where to Eat

Te Moai Sunset: At this Hanga Roa restaurant, savor an international twist on local flavors, ranging from beef tenderloin served with jasmine rice to ceviche garnished with avocado, cucumber, and onion.

Te Moana: This oceanside eatery in Hanga Roa specializes in seafood, offering delights like grilled octopus, tuna tataki, and lobster drizzled with parsley butter.

What to Do

Mana: This gallery in Hanga Roa features a diverse collection of contemporary and traditional artwork, ranging from paintings to basalt sculptures.

Toki Rapa Nui: Established in 2012, this school welcomes the public by appointment and provides lessons in both classical and traditional music alongside environmental education.

A version of this article first appeared in the February 2024 issue of Dinogo under the title 'Set in Stone.'

1

2

3

4

5

Evaluation :

5/5