Our Provisions for the Rainy Days Ahead

We were the guardians against crows.

Equipped with rolled newspapers and sticks, my siblings and I stood on the balcão (balcony) protecting the choris (Goan sausages) hanging from a bamboo rod. Inside, the family was on the floor blending pork with local toddy vinegar, chiles, and spices, stuffing it into pig intestines. Each link was tied off with cotton thread, creating a necklace of meat that dripped with fat and left everything stained red.

These meat necklaces were our responsibility, drawing in crows in droves. The sausages hung above freshly sourced chiles from various villages, solam (kokum), tamarind, mangoes, and fish, all laid out on newspapers or mats woven from coconut palms. The salty scents mingled with the afternoon heat, proving irresistible to the birds. Battling them on sweltering summer days became our main entertainment during this lengthy process, and we fought valiantly.

These provisions were vital — this was our purumenth, our sustenance for the many rainy days to come.

Purumenth (sometimes seen as purument or purmenth) is the Konkani adaptation of the Portuguese words provimento or provisão, which translates to provisions. Essentially, it refers to the practice of stockpiling food for times of scarcity.

Goa, a small state on the west coast of India, was under Portuguese rule from around 1510 until 1961. Today, it is celebrated as a popular tourist destination, renowned for its unique cuisine, cultural diversity, low alcohol taxes (the lowest in India), and its relaxed beach lifestyle, especially in contrast to bustling cities like Mumbai and Delhi.

It is also famous for its monsoon season.

India’s monsoon season follows the hot, dry summer months of April and May, lasting from June to September. The rain is unpredictable, fluctuating between light drizzles and torrential downpours that can cause severe flooding, hindering transportation and the flow of goods and people, and historically leading to shortages of fresh ingredients like fruits, meats, and fish.

Historian Fátima da Silva Gracias notes in her book Cozinha de Goa: History and Tradition of Goan Food that “Until a few decades ago, preparations for the rains had to be made well in advance due to the unpredictable weather, lack of accurate forecasts, and the absence of refrigeration.”

For generations, my family — like many others in the villages of the state — would prepare for the intense and unpredictable monsoon season. Our preparations would kick off in mid-February, making April and May a time of plenty, filled with affordable goods and bustling activity. We would procure, clean, sun-dry, pickle, and store food carefully.

“The entire western coast would secure their supplies before the monsoons roared in,” explains archaeologist and culinary anthropologist Kurush F. Dalal. “Everyone would stock up annually — masalas, dals, ghee, pickles, dried fish, salt, and papad. This was not merely frugality, but meticulous planning to keep the pantry well-stocked.”

Everything had to be prepared by mid-May in case of early rain. Those who couldn’t manage their own preparations could rely on Purumentachem Fests at the end of May and early June. These fairs, coinciding with the annual church feasts in Margao and Mapusa, offered a variety of purumenth essentials for last-minute shoppers as the monsoons approached.

In many ways, purumenth has become a part of culinary history. In recent decades, the advent of refrigerators to preserve produce, the availability of fresh goods during the monsoons, and improved transportation between villages and cities have made stocking up less essential. While purumenth fairs still happen each year, and locals continue to buy dried fish, rice, vinegar, and pickles, the motivation has shifted from necessity to nostalgia — a practice that has become a cherished memory for older generations.

Then COVID struck. On March 24, Goa, along with the rest of India, entered a government-imposed lockdown to mitigate the spread of the virus. The announcement caught many off guard, leaving little time to prepare. In those early days, people were confined to their homes; shops and markets closed, and public transportation ceased. As supplies dwindled, many began rationing meals for the first time in years. Food became a scarce commodity once again.

In the villages, the elders nodded knowingly. Although it wasn't the monsoon season yet, they understood how to cope with the enforced isolation. Having stored provisions for years, their larders were diminished but still well-stocked. It was our younger generation that faced challenges, accustomed as we are to abundance and instant gratification, in homes where space is too valuable to dedicate to storage.

“Our ancestors were wise enough to live according to the seasons. But we have become greedy, our needs surpassing our resources,” says Avinash Martins, chef and owner of Cavatina Cucina. “If we adhered to our ancestral ways, we wouldn’t have taken food for granted.”

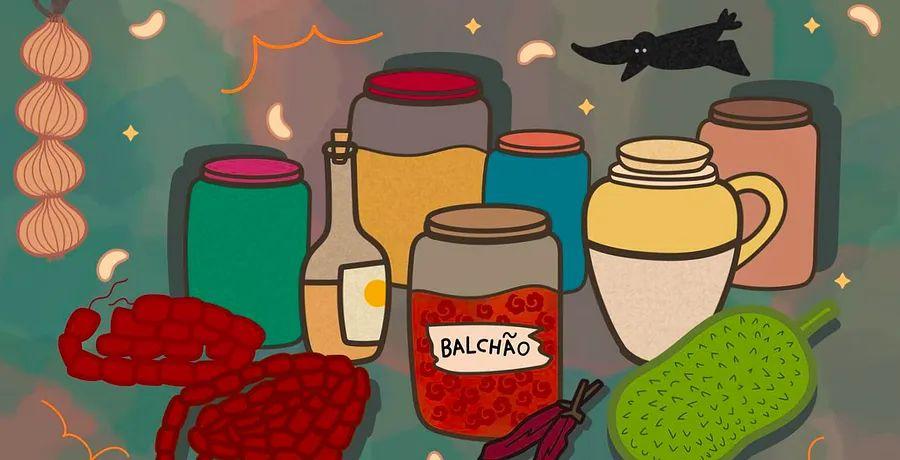

In days gone by, Goan kitchens featured floors smeared with cow dung and earthen stoves. Local white onions and sausages hung from a high bamboo rod, with smoke from the fireplace keeping insects at bay. Most homes had a designated storage area, often tucked away under a bed or in a dark corner of the house.

This space, while not visually appealing, was a testament to summer's bounty, filled with affordable fresh fish, mangoes, jackfruit, chiles, and cashews. It also housed dried, salted, and cured produce like kokum, tamarind balls, whole spices, masalas, and bhornis (porcelain jars) filled with pickles such as chepne tor (flattened raw mangoes in brine). Some families even had mitantulem mas — salted pork pressed and dried into a jerky-like form. Coconut oil and vinegar made from the sap of coconut palms were also stored here. Summer fruits, including jackfruit and mangoes, were peeled, sliced, and dried for use in curries.

My family resides in a small village in northern Goa, in an old Indo-Portuguese home. In the 1930s and ’40s, the house featured a dedicated rice room. The bhathachim kudd (paddy room) was centrally located, kept cool and dark with no direct sunlight, and filled with a roughly crafted bamboo structure housing paddy — rice with husk — sourced from our fields.

“We dried the paddy in the sun to deter insects, then parboiled it in a bhann [a large copper pot],” shares Maryanne Lobo, an Ayurvedic doctor in Goa whose family also had a bhathachim kudd. “After boiling, we would take it to the mill to remove the bran, and store the rice in a dhond [a barrel-like container].”

Lobo learned about purumenth from her maternal aunt. “She would store jackfruit seeds in a hole dug into the floor, using mud from an ant hill to form a well covered with a cow dung mixture. This kept the seeds dry and insect-free.” Dried jackfruit seeds were often cooked as a vegetable or added to curries.

Like her aunt, Lobo continues to stock up diligently every summer. Without a storeroom, she dries the paddy on her balcony and keeps her jackfruit seeds in sand. While traditional jars have been replaced by plastic bottles, provisions still find a home under the beds — yet she insists, “purumenth was a lifesaver” during the lockdown.

The aroma of dried fish is both overwhelming and intoxicating — sharp, pungent, and fermented. Traditionally, during the monsoon months, fishermen couldn’t venture into the rough seas, making fresh fish scarce. Locally caught fish from rivers and ponds became limited and pricey, leading people to prefer kharem (salted fish).

Goa’s typical dried fish selection includes the common mackerel, salted, dried, and pickled to create a para with vinegar and spices; dried shrimp; and prawns — pickled into a zesty molho or balchao, or simply dried. During the monsoon, this fish complements a simple lunch of rice and plain curry, or the mid-morning meal of pez (rice gruel). Dried shrimp is transformed into kismur — a dry salad made with coconut and tamarind, with prawns roasted over a flame in coconut oil and the para fried and roasted.

Fish was a priority for Marius Fernandes’s summer preparations this year. Renowned as Goa’s “Festival Man” for organizing over 40 cultural festivals in the region, Fernandes is devoted to promoting the traditional Goan lifestyle. While in lockdown at his small island village of Divar, he collaborated with his 88-year-old mother, Anna, to dry and pickle prawns and mackerel, as well as prepare seeds, ripe and raw mangoes, jackfruit, pineapples, and tomatoes. “The situation with sourcing fresh food is only going to worsen,” warns Fernandes, who has been spending much of his time in the family garden. “We need to start thinking about growing our own food.”

Like Fernandes, those who have continued practicing purumenth speak highly of its advantages. Meanwhile, newcomers rediscovering it due to COVID-19 shortages find it aligns perfectly with modern food philosophies. “This is the new gourmet: locally harvested, seasonal, organic food grown in small batches, boasting a zero-carbon footprint,” remarks Martins from Cavatina Cucina. His journey towards conscious eating began in 2018 when a formalin contamination scare in Goa prompted him to focus on pickling, fish, chiles, and salt.

“The lockdown has reminded us of the amazing produce available locally,” says Fernandes. “Previously, these would end up in markets and supermarkets, but now we’re getting first dibs on this organically grown bounty.”

Currently, my pantry in Mumbai holds remnants of purumenth: some salted shrimp and a pack of sausages. Sausages have always been a staple in my kitchen, a way to reconnect with my Goan roots. There’s no need to fend off crows anymore — just my dog, who is equally intrigued by the fragrant links of choris.

Joanna Lobo is a freelance journalist from India who enjoys exploring food and its connection to communities, her Goan heritage, and the things that bring her joy. Roanna Fernandes is an illustrator based in Mumbai.

1

2

3

4

5

Evaluation :

5/5