Palestinians Uphold Grape Cultivation and Heritage in the West Bank

By 6 a.m., Jamil Sarras, a Palestinian viticulturist, is already polished and articulate. I met him one September morning to harvest grapes before the day warmed up. While he works as a medical lab specialist in Bethlehem, he also manages the Sarras Family Vineyard, located about 40 minutes from the city of Hebron, or Al-Khalil in Arabic. Each year, starting in late August, Jamil and his family spend one to two months picking grapes, which he sells to Palestinian wineries and arak producers.

Grapes rank as the second most cultivated fruit in Palestine, following olives, and the region enjoys three distinct harvests. The first occurs in early spring when farmers collect the leaves, which, when used for waraq dawali, command prices five times higher than the grapes. A couple of months later, unripe grapes are harvested for hosrum, a sour condiment that adds a distinctive tang to Palestinian dishes.

Finally, in late summer, the grapes are ready for harvest. Beyond being enjoyed fresh, they are transformed into wine, arak, vinegar, raisins, and dibs—a winter grape molasses mixed with tahini and served with bread, likened to a “Middle Eastern peanut butter and jelly sandwich” by food writer Reem Kassis in her book The Palestinian Table.

As we approached the last clusters to pick, Sarras led me to a spot where I could survey the entire vineyard. The landscape differs significantly from that of European and American vineyards. Instead of traditional trellises, Palestinian growers anchor their vines to sturdy metal stakes embedded deep in the earth. The vines create thick trunks around the stakes, forming leafy canopies over the grapes, enabling farmers to manage ripening: by trimming the canopy, they can expose the grapes to sunlight and hasten their ripening when demand is high.

An unusual sight on European vineyards, the white walls of an Israeli settlement loom over Sarras’s vineyard from a nearby hill. Located in an area known to Israel as Gush Etzion, the Sarras vineyard is situated in a region where the Israeli government has both actively supported and passively permitted the encroachment of Israeli settlers. International law considers these settlements illegal, with the U.N. designating the Etzion settlement bloc as a significant settlement area in the West Bank. In 2020, the Washington Institute for Near East Policy reported approximately 100,000 settlers in Gush Etzion, a number that has since increased.

A view from the Sarras Family Vineyard, featuring the white walls of an Israeli settlement (center).

A view from the Sarras Family Vineyard, featuring the white walls of an Israeli settlement (center). As the settlement area has expanded, tensions have escalated into violent confrontations with local Palestinians. The U.N. reported a marked increase in settler violence against Palestinians during the first half of 2023, leading to casualties, damage to property, and displacement. To access his vineyard, Sarras must navigate through an intersection that was once a flashpoint of violence. The vineyard, located beneath the Gush Etzion settlement, has always been overshadowed by an ever-present threat. Recently, that vague anxiety has transformed into a real existential danger for Sarras and his family.

'We are confined in our home,' Sarras expressed on October 16. 'Every route connecting us to the outside world is blocked as part of a collective punishment.'

On October 7, Hamas, the Palestinian militant group governing the Gaza Strip, launched an unexpected assault on Israel, resulting in over 1,400 fatalities, predominantly among civilians, and the abduction of hundreds. In retaliation, Israel declared war on Hamas and initiated a weeks-long aerial bombardment of Gaza, which, according to the Gaza Health Ministry, has resulted in the deaths of 8,000 Palestinians. Israel also tightened border controls, hampering humanitarian aid access and limiting news flow. On October 27, the Israel Defense Force escalated its ground operations in Gaza, with Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu foreseeing a “long and difficult” conflict ahead. Today, Israeli troops struck Gaza City.

Heightened violence has also spread to the West Bank, raising concerns that the conflict focused on Gaza could expand into a broader regional crisis. Clashes between Israeli forces and Palestinians, alongside attacks by armed settlers, have led to the deadliest weeks for West Bank Palestinians in 15 years. Although the Palestinian Authority governs the area, not Hamas, Israeli forces have conducted raids and even launched an airstrike—a historically rare occurrence in the West Bank—targeting militants from Hamas and the Palestinian Islamic Jihad. Travel within the West Bank has been heavily restricted, complicating movement for aid workers and residents alike.

After some negotiations, Israeli forces ultimately permitted Sarras to visit his farm to feed his animals, on the condition that he avoids the vineyard, which he believes is “because they want to keep people away from the settlements.”

Sarras and his family have tended their land for generations. The region surrounding Gush Etzion, known to Palestinians as Al-Shefa, meaning a healing spa, is home to 85 percent of Palestine’s vineyards. This area represents the most fertile land in the Palestinian territories, serving as the agricultural heartland for Bethlehem and Hebron. Now, Sarras finds himself without access to his grapes, facing a murky future amidst escalating conflict.

“The remaining grapes are still on the vines and will spoil very soon because we can’t reach our vineyard,” he lamented.

Just like the fertile earth Sarras showcased as we walked through the fields that September morning, it all seemed precarious, ready to slip away.

On the day I visited the vineyard in September, Sarras was harvesting dabouki grapes. Before supermarkets offered grapes year-round, Palestinians eagerly awaited the dabouki, the season's first grapes, prized for their unique blend of sweetness and slight tartness, known as fateer in Arabic, meaning not fully ripe.

Sarras noted that the dabouki grape has lost some of its market appeal, saying, “but it’s ideal for making malban.” This traditional Palestinian fruit leather, preserved much like a fruit roll-up, combines grapes, nuts, and spices, serving as a delightful and healthy snack between meals.

During the Second Intifada, the early 2000s Palestinian uprising against Israeli occupation, Sarras faced economic challenges that hindered the sale of his grapes. In response, he began producing large quantities of malban from his unsold harvest. The family discovered that customers loved it, and they have continued making malban ever since, especially known for their unique use of nigella seeds from Hebron. The batch we were about to prepare together, he mentioned, was already sold out due to preorders.

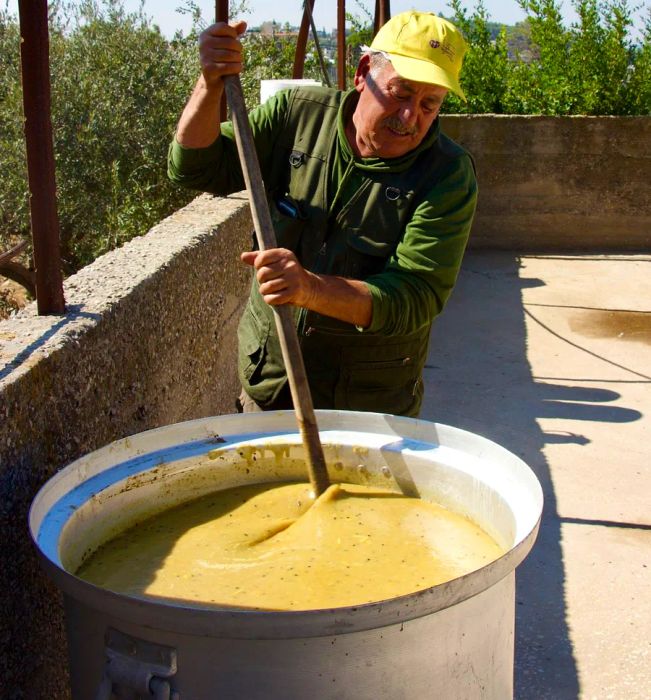

Abu Muhammad, a worker, stirs the malban to ensure the thick mixture doesn’t adhere to the bottom of the pot.

Abu Muhammad, a worker, stirs the malban to ensure the thick mixture doesn’t adhere to the bottom of the pot.Creating products like malban and dibs is labor-intensive and costly, yet amidst a constantly shifting political landscape, they serve as vital ways to uphold the Sarras family’s culinary traditions. At the same time, grapes, along with other crops, are deeply entwined in the region’s tumultuous history.

Agriculture has been a focal point of the conflict between settlers and Palestinians in the West Bank. According to the U.N. Office for Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, agricultural communities, particularly herders, face heightened risks of attack. Palestinian farmers have suffered land loss, crop destruction, and threats to their safety. On October 28, amidst a rise in settler violence following Israel’s conflict with Hamas, settlers killed a Palestinian farmer while he was harvesting olives.

Violence has also been directed at settlers by Palestinians in the West Bank: The New York Times reports, based on U.N. data, that an outbreak of violence in early 2022 resulted in casualties and injuries that were “roughly comparable” between both groups. However, the consequences have seldom been equal; as violence has surged over the past six years, particularly during harvest times, rights organizations have accused the Israeli military of not intervening during settler assaults and failing to hold Israeli offenders accountable, while prosecuting Palestinians instead.

“Settlers frequently set fire to olive and grape groves,” Kassis remarked on August 21, noting that land cultivated by Palestinians for generations “is illegally seized by settlers, and [Palestinian] farmers are barred from accessing [their land].”

Farmers are likely to face further land losses if the Israeli government proceeds with the annexation of the occupied territory. In 2019, Netanyahu promised to annex parts of the West Bank; this plan gained momentum following U.S. support during Donald Trump’s 2020 peace initiative and again when the Netanyahu administration curtailed the power of the supreme court in July 2023. With the declaration of war, the future of annexation remains uncertain. While the specific territories to be annexed could vary, Machsom Watch, a group of Israeli women monitoring human rights violations in the West Bank, suggests that Israel is likely to seek “to annex the Gush Etzion region in a permanent settlement with the Palestinians.” Even in the most limited annexation scenarios, the settlement bloc would probably be absorbed into Israel.

The large concentration of Palestinian vineyards in this region means that annexation would devastate the Palestinian grape industry, affecting associated sectors such as wineries, distilleries, vinegar makers, and raisin producers.

“For agro-businesses like mine that rely on grapes as the primary product, I’m unsure of what the future holds,” said Nader Muaddi, a Palestinian distiller at Arak Muaddi in Beit Jala, during our conversation in August. Muaddi utilizes Sarras’s grapes to craft arak, a traditional anise-flavored spirit prevalent in the Levant. “I could consider sourcing grapes from other regions like Jenin, but the shipping costs would be as high as the grapes themselves.”

With right-wing settlers such as Bezalel Smotrich and Itamar Ben-Gvir occupying significant ministerial roles, planning for the future is challenging, as annexation could dramatically alter the landscape of the West Bank.

“It’s incredibly unpredictable,” Muaddi noted. “It’s neither sustainable nor stable at all.”

Most Mytouries have remained shut since the latest conflict erupted between Israel and Hamas, yet Palestinian grapes have long been essential to both Palestinian and Israeli culinary creations prior to October 7. Asaf Doktor, an Israeli chef who owns multiple hyperlocal restaurants in Tel Aviv — Dok, Ha’Achim, and Abie — has always preferred to source his fruits from Palestinian farmers, including grapes.

At the flagship Dok — which temporarily ceased regular operations on October 8 and just reopened for standard service yesterday — the chef had crafted a variation of the Palestinian musakhan; typically, roasted chicken and onions are placed atop taboon flatbread, but at Dok, quail took the place of chicken, house-made Khorasan wheat pasta replaced the flatbread, and a pasta sauce was enriched with wine and plump raisins from Philokalia, a skin-contact winery based in Bethlehem. Doktor also favored using Palestinian grape molasses to enhance vinaigrettes and other sauces.

Fattoush, hummus, and grape leaves prepared two ways at Kabakeh in Jaffa.

Fattoush, hummus, and grape leaves prepared two ways at Kabakeh in Jaffa. Asaf Doktor’s interpretation of Palestinian musakhan.

Asaf Doktor’s interpretation of Palestinian musakhan.“Dibs is one of my favorite molasses; it has a very traditional vibe,” he shared with me in August. “Acidity plays a crucial role in our cuisine,” he continued, “and we select acidic ingredients based on the season.” Since lemons are a winter fruit, Doktor’s restaurants often switch to hosrum, the tart grape condiment during summer. “Hosrum works better with proteins [like my carpaccio and sashimi] because it doesn’t cure the meat or fish like lemon does.”

Habib Daoud, the chef and owner of two Palestinian restaurants in Israel featuring Galilean cuisine — Kabakeh in Jaffa and Ezba in Rameh — referenced the concept of baladi, which is common among Palestinian farmers, to describe the quality of the agriculture.

“Baladi signifies a place, a fragrance, a way of growing crops — it embodies an overall mindset,” he explained in September. For Daoud, this philosophy is represented by a small garden adjacent to the home of the fellahin (farmer), who maintains a deep connection to the land. Because the yield is modest, the community shares resources, contributing to festive meals. This sense of community infuses Palestinian grapes and cuisine with distinctive flavors, according to Daoud.

This is also why chefs like Doktor and Daoud prefer to source produce from local Palestinian farms. The principles of baladi resonate with the Slow Food movement, which champions local agriculture and results in exceptional seasonal ingredients.

“From my visits to West Bank markets,” Daoud remarked, “I can taste the distinction between Israeli produce and that from Palestinian farms, especially when it comes to fruits.”

Philokalia wine, featured and sold at Asaf Doktor’s restaurant, Dok.

Philokalia wine, featured and sold at Asaf Doktor’s restaurant, Dok.As the sun warmed the vineyard that September morning, Sarras led me to his home, where his family was preparing to process the grapes for malban. At the entrance, I was welcomed by Carlos Sarras, Jamil’s father. Now in his 80s, Carlos has dedicated his life to grape cultivation.

The initial step in crafting malban involves extracting juice from the grapes. In the past, the family would stomp on the grapes, Carlos shared, but now they use a machine for convenience. After straining out the seeds and skins multiple times, they allow the juice to simmer in a large pot, a process that can take considerable time. While we waited, the family invited me to enjoy a breakfast of stewed tomatoes, hard-boiled eggs, olive oil, and za’atar.

During breakfast, I learned more about the family's background. Carlos grew up near Bethlehem, but his mother hailed from Palestine, born in Chile. Like many Palestinian families, the Sarras clan has relatives scattered throughout the diaspora worldwide.

In recent years, Palestinians in the diaspora have gained prominence through new restaurants and cookbooks. This movement includes a new wave of Palestinian chefs who are modernizing their cuisine to widespread acclaim. While stuffed grape leaves are a staple at many of these Mytouries, grape products from Palestine often struggle to reach beyond the territories. You might find Arak Muaddi and Philokalia wine in select liquor stores and restaurants in the U.S., but items like malban and dibs are much harder to find.

However, this international culinary recognition is just a fraction of its potential. Kassis points out that one major threat to Palestinian food culture is “the misleading marketing of many of our dishes abroad as Israeli, effectively erasing our identity.” She shared her frustrations with the Washington Post, recalling her arrival in the U.S. and seeing beloved childhood dishes served in Israeli restaurants without any acknowledgment of their Palestinian roots. Despite recognition from leading Israeli food scholars that dishes like hummus and falafel were first learned from Palestinians, the erasure persists.

After boiling the malban, Jamil Sarras and his mother transfer the mixture onto a sheet of heat-resistant plastic on their porch.

After boiling the malban, Jamil Sarras and his mother transfer the mixture onto a sheet of heat-resistant plastic on their porch. Sarras incorporates nigella seeds into the pot of malban.

Sarras incorporates nigella seeds into the pot of malban.“We, the Palestinians have been stewards of these grapes, nurturing and preserving them for generations,” Muaddi remarked, noting that the community has safeguarded 23 unique heirloom grape varieties for thousands of years. “It would be a tragedy to lose this aspect of viticulture, as it is deeply woven into Palestinian culture.”

This is just one of the many efforts Palestinians are making to protect their culinary heritage amidst the ongoing threats of violence and annexation. The Palestinian Heirloom Seed Library in Battir, located just across the valley from the Sarras family home, conserves various seeds and distributes them to local farmers. Today, seeds from the library can be purchased in the U.S., enabling Palestinians in the diaspora to plant a piece of Palestine in their own gardens.

As we wrapped up our breakfast at the Sarras home, the grape juice had finally boiled down enough, and we mixed in nuts and seeds, giving the malban a delightful blend of chewiness and crunch. We also added spices like aniseed, turmeric, and sesame seeds, which subtly enhance the natural flavor of the grapes. Finally, we incorporated a blend of flour and well water to achieve the right thickness.

The final step of the day involved pouring the mixture onto heat-resistant plastic and spreading it into a thin layer to dry for a week. Carlos mentioned that in the past, they used bedsheets for this, but switched to plastic due to the mess it created. “The sheets were a hassle,” he noted.

As I said my goodbyes, I planned to return at the end of the harvest to make dibs. However, with the outbreak of war, I have not been able to return to the Sarras home.

“The situation is dire, and we remain hopeful,” Sarras told me on October 16. “Escalation begets escalation, leading to more radicalization on both sides. Too many lives have been lost.”

The wait for malban to solidify or grapes to mature pales in comparison to the generations-long wait for peace. Yet the processes of juicing, cooking, and drying grapes highlight the paradoxical yet essential efforts of the Sarras family and the Palestinian community to safeguard their traditions from complete erasure. This work must persist, as many grapes still hang unpicked on the vines.

Adam Sella is a journalist based in Tel Aviv covering Israel and Palestine. His writing spans topics from food and the environment to war and conflict.

The malban created by the Sarras family.

The malban created by the Sarras family.

1

2

3

4

5

Evaluation :

5/5