S1, E6: Navigating the Dos and Don'ts of Cultural Tourism

Join us on our latest podcast episode of Unpacked by Dinogo, where we delve into the realm of responsible travel in an engaging and enjoyable manner. Every other Thursday, we tackle your ethical dilemmas, from the appropriateness of animal tourism—like swimming with dolphins instead of riding elephants—to eco-conscious travel practices, such as understanding zero-waste travel and its feasibility. Check out the transcript of our episode from August 25.

Transcript

Jennifer Flowers, host: Welcome to Unpacked. I’m Jennifer Flowers, the senior deputy editor at Dinogo. Have you ever found yourself in a breathtaking cultural moment while traveling, wondering if snapping a photo is appropriate? Or have you encountered a traditional performance and debated your presence there? These instances, along with the questions they evoke, embody cultural tourism. Today, we’ll dive into those inquiries and much more.

From a young age, I embraced the spirit of travel. Growing up in a family with a hotelier father, I lived in places like Hong Kong, Singapore, the Philippines, and the U.S. Naturally, I pursued a career as a travel editor. Throughout my life, I’ve been privileged to have remarkable experiences worldwide. Yet, some of my most transformative moments have come from connecting with diverse cultures. I’ve walked alongside the San people in Botswana's Kalahari Desert, stayed with a Tibetan family in rural China, and enjoyed yak butter tea with Sherpas in the stunning Himalayas of Nepal.

I’ve faced some tough experiences too. I still feel uneasy recalling a day spent in the Atlas Mountains of Morocco. I snapped a distant photo of a group of Berber people perched on a rocky ledge. Their frowns and gestures made it clear that I had crossed a boundary, and to this day, I regret invading their privacy.

I strive to act thoughtfully in these situations, but I know I can improve. Sometimes, I’m left completely uncertain about what to do. This prompted me to consult several experts who represent Indigenous communities and constantly reflect on these issues.

Kalani Ka‘anā‘anā is a Native Hawaiian whose family has lived in the O‘ahu town of Kailua for generations. He practices hula, speaks Hawaiian fluently, and serves as the chief brand officer at the Hawai‘i Tourism Authority.

Kalani shares his thoughts on the phrase 'cultural tourism.'

Kalani Ka‘anā‘anā: The term seems to treat culture as a means to an end, making it feel somewhat transactional. For me, our culture embodies our worldview—how we see things and our connection to aina, or the land. We view land, ocean, and all elements as family. However, translating this perspective into the realms of hospitality and tourism can be challenging.

At its core, one might view cultural tourism as a visitor's longing to immerse themselves in a place and experience an authentic representation of its culture. This is where things become complicated, and why we’re having these important discussions today about its implications.

Jennifer: Kalani and other residents of Hawai‘i are grappling with tough questions regarding the interplay between Native Hawaiian heritage and tourism, which stands as the state’s largest economic driver. How does Hawaiian culture gain from tourism, and in what instances is it being commercialized to the point of losing its essence?

Kalani: In Hawai‘i, we have a complex historical relationship with hospitality, performance culture, and the stereotypes that accompany them—like the kitschy Tiki culture. The industry has often depicted Hawai‘i in a romanticized and overly sexualized light, focusing on coconut bras, grass skirts, mai tais, and beaches. However, Hawai‘i has a much richer and more profound significance, filled with spiritual energy and much more than just hula girls.

Jennifer: Kalani’s remarks resonated with me. My Japanese American mother grew up in Hawai‘i. While we don't share Kalani's Native Hawaiian experience, we have witnessed the adverse effects of cultural appropriation—evidenced by the hit HBO series White Lotus and the troubling power dynamics it highlights. Hawaiian culture is not unique in facing these challenges.

The World Bank reports that Indigenous peoples constitute 6 percent of the global population yet represent 19 percent of those living in extreme poverty. For centuries, Indigenous communities have endured displacement, discrimination, and violence, often missing out on the economic benefits of tourism that is inspired by their own cultures.

Indigenous peoples serve as the primary stewards of our natural environment, holding, inhabiting, or utilizing 80 percent of the world’s most biodiverse regions. Their deep ancestral ties to the land often span back thousands of years. As travelers, we naturally seek to explore and connect with these remarkable cultures.

Considering all this, what does an experience look like that genuinely benefits Indigenous communities?

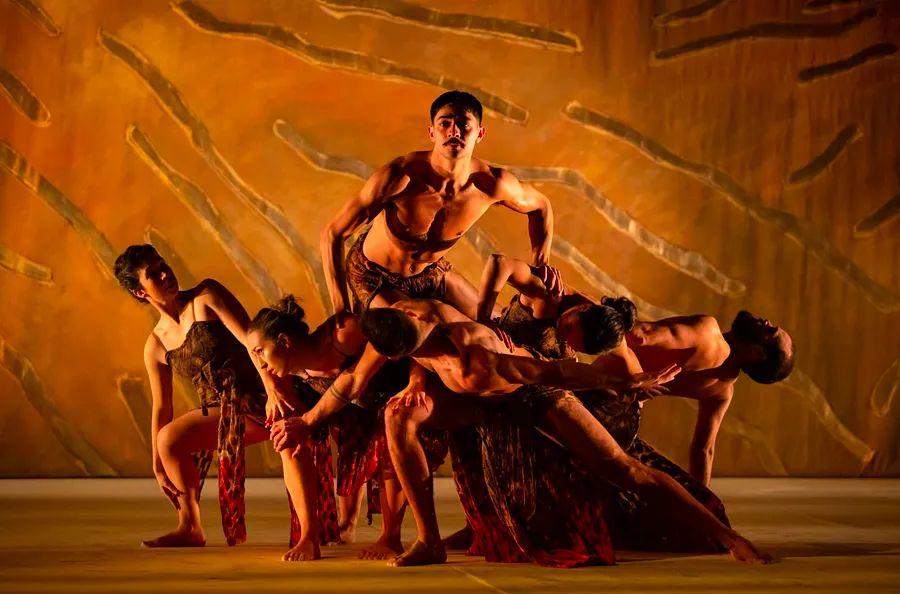

Photo by Daniel Boud

Frances Rings: Cultural tourism holds great significance. It should originate from the community and the people themselves, ensuring they reap the economic benefits, and it must be conducted in a manner that reflects their wishes and the way they wish to share their culture.

Jennifer: This is Frances Rings, the associate artistic director of Bangarra, a contemporary Indigenous dance company located in Sydney. Frances’s mother hails from the Kokatha tribe on the west coast of South Australia. Set to become Bangarra’s artistic director in 2023, Frances collaborates with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander groups, who grant Bangarra the right to share traditional stories through contemporary dance.

We discussed the various ways visitors can connect with culture in Australia. For a theatrical experience, they might purchase a ticket to a Bangarra show in Sydney, or venture into the countryside for a guided walk with someone whose ancestral ties to the land stretch back millennia, learning about the region's creation stories. However, the key to any cultural experience, according to her, is that it should be led by the custodians of that culture. She shared the broader questions she contemplates regarding cultural tourism.

Frances: I believe we must consider how to approach this with integrity, ensuring we don’t compromise our identity. How do we safeguard what is sacred? What elements can we share with the public to raise awareness about who we are? This allows our youth to see that their culture is valued and acknowledged, which in turn creates jobs and brings economic benefits that enhance community resources and support growth.

Jennifer: Creating a culturally sensitive experience requires time—often a significant amount. When Frances receives permission to develop new choreography with a community, it can take months, sometimes even years. This is necessary to build a relationship and comprehend how they wish their story to be represented.

Frances: Translating that information must be approached with care and respect. With 400 language groups rich in song, dance, stories, customs, arts, laws, and knowledge, each community is unique. We must be guided by how they want their narratives shared, ensuring that everything is community-driven. Engaging a cultural consultant from that community is crucial—they act as a vital connection.

Jennifer: At the outset of a new project, she reflects on the essential questions: What story is unfolding? Why does it matter? How will it deepen people's understanding of Australia? In her nine-part choreographic piece, Terrain, Frances traveled to Kati Thanda, or Lake Eyre, in northern Australia, connecting with the Arabunna people. She spent meaningful time with Reginald Dodd, an elder from the Arabunna community. During their time together, a vision emerged that inspired the piece "Spinifex," the third installment of Terrain.

In its simplest sense, cultural tourism can be seen as a visitor's longing to immerse themselves in and witness authentic cultural expressions. However, this concept can quickly become complex.

Frances: I remember a moment when I sat by the lake, gazing into the horizon where everything was still and the shimmering mirage danced above the water. In the distance, I spotted trees that resembled women, gently arching and intertwining as if they were breathing. I sensed the presence of ancestral women, suspended in this vast space, waiting for the life-giving waters to transform the desert around them.

This image lingered in my mind, leading to the creation of my piece titled "Spinifex." The ancestral women inhabit this space, their forms distinctly feminine yet ethereal. It is a celebration of womanhood, an homage to our movements and the heritage we carry from our mothers and grandmothers—what other medium allows such a profound sharing?

Jennifer: Just hearing Frances describe the scene that inspired her work sent chills down my spine. She provided me with a fresh, profound understanding of the local people and their landscapes. These rich perspectives are exactly what she hopes to convey to audiences attending Bangarra performances.

Similar to Frances, Kalani contemplates the preservation and continuation of Hawaiian traditions, particularly concerning hula, the beloved dance form he has dedicated over 15 years to studying and practicing.

Kalani: When considering how hula is showcased within the tourism and hospitality sectors, it’s crucial to recognize that this presentation often occurs within a foreign context. Sharing our culture for monetary gain was never our tradition. Therefore, we begin from a position that feels somewhat unusual. Is it negative? Not at all. Do we need to evolve with the times? Absolutely.

Jennifer: Kalani introduced me to the two primary forms of hula found in Hawaii: ‘auana, a contemporary style accompanied by music, which was developed for travelers in the early 20th century and stands as a valid art form in its own right, inviting visitors to engage with it. The other is kahiko hula, the ancient style steeped in ceremony and ritual, performed with chanting, which is generally not meant for public display.

Kalani: In Hawaiian culture, we have a concept called au’a, referring to things that are intentionally kept sacred and hidden. Some aspects of our culture are meant to remain behind this veil of sacredness, while others, like modern hula, particularly hula ‘auana—accompanied by string instruments—are more accessible. This evolution of hula, music, and dance is celebratory, made for enjoyment and gatherings.

Jennifer: In essence, when you witness a hula performance at a hotel, feel free to embrace the joy of the experience in a setting where the performers are eager to share their art with you.

When people think about cultural tourism, performance art often springs to mind first. However, some of the most impactful connections occur in unscripted interactions. During a trip to Colombia in 2021, I was among the first travelers to engage in a new cultural experience. Colombia-based outfitter Retorno Travel aimed to connect travelers like myself with the Wounaan community, who have been displaced from their ancestral land in the Colombian jungle near Panama and now reside in Bogota.

We visited their community center, where we were invited to join in a spiritual dance and enjoy a meal of steamed fish and plantains with them. After lunch, the elders began to share, through a translator, their deep-rooted connections to the land and the challenges they faced when forced to abandon their way of life due to illegal guerrilla warfare. This is where our discussions truly became engaging.

The community healer openly expressed his mixed feelings about tourism and the impact of photographers capturing their lifestyle. He lamented that urban living was pulling the younger generation away from their cultural heritage. Shortly after, the schoolteacher placed a black tree seed from his jungle birthplace in my hand. I struggled to hold back tears as he explained that whenever I felt the need to reconnect with nature, I could simply close my eyes and feel the rough texture of the seed on my fingers. I still keep that seed on my bedside table today.

Authentic connections like these are at the core of Wild Expeditions Africa, an outfitter offering experiences in Ethiopia, Madagascar, and Zimbabwe. Wild Expeditions operates mobile camps that venture into rural areas of Ethiopia where tourism infrastructure is limited. One of their permanent camps in the culturally rich Omo Valley is called Lale’s Camp, managed by Lale Birwa, a member of the local Kara ethnic group. In this area, many staff members come from the villages that guests visit, fostering strong relationships with the communities. Bemnet Gizachew, one of Wild Expeditions' founders, oversees the mobile tented camp operations in Ethiopia.

Photo by Andy Haslam

Bemnet Gizachew: Our goal is to provide an authentic travel experience for our clients. When travelers visit specific tribes, the aim goes beyond just capturing great photos. It’s about establishing a genuine human connection and learning from one another. It's not just the travelers who gain knowledge; the tribes also learn about the visitors who come to see them.

Jennifer: Bemnet was raised in Addis Ababa, where he cultivated a love for history and literature, which fueled his interest in different cultures and led him to the travel industry. As a guide, he’s observed that some tour operators prefer to visit easily accessible villages, often just lining up villagers for posed photographs. This approach to cultural interaction made me uneasy. In contrast, Wild Expeditions focuses on fostering genuine connections. Bemnet and his team encourage guests to engage with elders and observe daily life before even thinking about taking photos. Once a respectful relationship is established, he believes it's appropriate to ask for permission to capture a moment.

Bemnet: We strive to gently communicate what truly matters here. For those seeking lasting memories, I advise them to put down their cameras and spend time with the people they’ve come to visit, rather than letting their cameras act as a barrier between them and the tribe.

Jennifer: Welcome back to Unpacked by Dinogo. Frances, Kalani, and Bemnet all highlighted the significance of two-way communication in cultural exchanges. It’s not solely about travelers benefiting from experiences; it's also about actively participating and sharing parts of ourselves. During a trip to Kenya in 2019, I was eager to learn Swahili but stumbled along the way. On a game drive one morning, while having breakfast in the bush, I intended to ask for coffee, or “kahawa,” but mistakenly asked for “kuhara,” which means diarrhea. My Masai guide, Nelson, quickly corrected me, leading to shared laughter. Moments later, I made another blunder by inquiring about how many cattle he owned—equivalent to asking about his bank balance in Western culture. I will forever remember the mix-up between coffee and diarrhea in East Africa, I won’t pry into a Masai’s finances, and I will always cherish the connections made that bright morning on the savanna.

I was intrigued by Bemnet’s insights regarding visitors to the Omo Valley. In some tribes, a man's wealth is often assessed by the size of his cattle herd. One of the first questions they pose to male guests is whether they own any cattle.

Bemnet: Typically, they ask our clients, “Do you own cattle? How about sheep, goats, or oxen?” When the response is, “No, we don’t have any,” the tribe members often express sympathy, saying, “I can give you some. It’s never too late to start, you know?”

Jennifer: I found it amusing to think that a visitor could possess countless yachts, mansions, and a substantial bank account, yet in this part of the Omo Valley, lacking cattle essentially means being considered impoverished—to the extent that locals might offer to donate cattle to them.

Travelers sometimes hastily judge a tradition or deem it outdated. However, Bemnet urges visitors to approach these cultures with an open mind.

Bemnet: When you visit the United States, you encounter families with their own unique cultures. The same applies to the tribes in the Omo Valley. When you find yourself in their territory, it's crucial to respect and understand their cultural perspectives instead of labeling them as 'backward' or 'underdeveloped.' Immersing yourself in their culture and learning from their viewpoint is far more beneficial for both travelers and the communities they visit.

Jennifer: Bemnet shared insights about the Mursi tradition where some women choose to wear lip plates, a practice involving the cutting and stretching of the lower lip to accommodate a disc made from clay or wood. For the Mursi people, this symbolizes beauty and social maturity. However, some travelers express to Bemnet that they believe the Mursi should abandon this practice, worrying that it might be painful or oppressive. In such cases, Bemnet encourages a focus on understanding the cultural significance behind the tradition instead.

Bemnet: Definitions of beauty vary widely. For some, being slim with long hair may represent beauty, but for the Mursi tribe, wearing lip plates is one of their beauty expressions. We must show respect as visitors and instead of passing judgment, seek to understand their motivations for this practice.

Jennifer: Reflecting on how to engage in cultural tourism more ethically, it became evident that much of this change relies on the travelers themselves. Ultimately, it’s the travelers who decide where to spend their money while traveling. Kalani elaborated on the significance of this responsibility.

Kalani: The most significant shift in tourism will likely stem from consumer behavior. As consumers become more conscious of their environmental impact, they will demand that tourism businesses and destinations consider their footprints. This awareness will be a powerful catalyst for change.

Jennifer: The more we educate ourselves about our travel experiences, the better equipped we are to foster meaningful relationships with the people and places we encounter. Building that trust can open doors to rich cultural experiences that enhance our travels. As our enlightening discussion concluded, Kalani invited me—and you—to listen to a special chant he composed in 2008, honoring his homeland.

Kalani: To truly understand Hawaiians, as well as Hawai‘i and our language, it’s essential to recognize that our identity is deeply connected to the land and relationships. This principle is not exclusive to Hawai‘i. Consider a place that rejuvenates you, inspires you, or brings you a sense of wholeness and well-being. As you prepare for your trip to Hawai‘i, remember that this is a place that provides that for us, and I'm happy to share it with you.

[CHANT]

Jennifer: Before we wrap up, let’s reflect on what we’ve learned about cultural tourism.

Takeaway #1

Research your destination and familiarize yourself with the cultures of the area you’re visiting. Move beyond dominant cultural narratives and explore Indigenous histories. Look for ways to engage with that history during your time there.

Takeaway #2

When considering a cultural experience, take the time to understand its origins so you know what you’re engaging with. Who controls this experience? Are the true custodians of that culture in charge? And is that culture gaining from the experience they’re sharing with you?

Takeaway #3

Approach with an open mind. Step into the experience without preconceived notions and allow the guardians of that culture to lead you. It may not always be a straightforward journey, but being an open and humble participant often fosters genuine cultural exchange.

Takeaway #4

Gaining access to a cultural experience is akin to stepping into a friend’s home. It’s important to respect your host's space, boundaries, and comfort levels—whether that involves asking for permission to take a photo or dressing appropriately.

Takeaway #5

A genuine exchange is reciprocal. Ask questions, but also encourage your hosts to inquire about you. Trust, connections, and mutual understanding flourish when both sides engage in learning about each other.

Takeaway #6

Travelers wield spending power, which can promote more ethical cultural experiences. By seeking out responsible cultural practices, you encourage outfitters and communities to provide these enriching encounters. This not only enhances your trip but also contributes to a more sustainable tourism industry.

Thank you for tuning into this episode of Unpacked. As a fellow traveler, I look forward to crossing paths with you. Connect with me on Instagram @jenniferleeflowers and Twitter @jennflowers.

Eager for more insights? Check us out at Dinogo.com, and don’t forget to follow us on Instagram and Twitter at @Dinogomedia. Our show notes have additional resources related to today’s discussion. If you enjoyed this journey, we’d love for you to return for more fascinating stories. Subscribing makes it simple! You can find us on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or your preferred podcast platform. Please take a moment to rate and review us, as it helps other travelers discover the show.

You’ve been listening to Unpacked by Dinogo, a production of Dinogo Media and Boom Integrated. Our podcast is brought to life by Aislyn Greene, Adrien Glover, and Robin Lai. Postproduction was handled by Jenn Grossman and Clint Rhodes from John Marshall Media. Music composition by Alan Carrescia, with special thanks for original music from Kalani Ka‘anā‘anā and composer David Page.

And remember: The world is complex, but being an ethical traveler doesn’t have to be.

1

2

3

4

5

Evaluation :

5/5