The Final Moments of Mexico City’s Cafes Chinos

I find myself with a massive plate of chop suey under the watchful eyes of Martin de Porres, the Catholic patron of racial harmony. His seriousness contrasts with the cheerful, rosy-cheeked baby dressed for the Chinese New Year depicted on the wall beside him. A busker enters, strumming a poignant Mexican bolero. Outside, Calle del Carmen buzzes with vendors selling imitation designer bags, inexpensive sunglasses, and dog accessories, while inside Cafe Goya, one of the last remaining cafes chinos, a quiet nostalgia lingers in the air.

Established by Chinese immigrants in the early 20th century, cafes chinos became beloved Mytouries for Mexico City’s working class, providing affordable, quick meals and a welcoming community hub. Most feature a 1950s diner vibe, complete with vinyl booths and long bars lined with swivel stools. Their menus boast a variety of straightforward, homestyle meals—some influenced by Chinese cuisine, others distinctly Mexican. Classic lunch options often include grilled meats with rice and a small salad, while breakfast might feature huevos al gusto. Grilled ham and cheese sandwiches are common too. While some cafes still serve fried rice, kung pao chicken, and sweet-and-sour pork, many traditional Chinese dishes have faded from the menus over time. Waitresses glide by with metal pitchers of cafe lechero— a blend of concentrated coffee and hot whole milk— while locals often drop in just to admire the tempting pastries known as pan chino displayed in the window.

The essential assortment of pan chino paired with cafe lechero at Café Allende.

The essential assortment of pan chino paired with cafe lechero at Café Allende.“Oh, that one’s absolutely delightful,” Jesus Chew tells me as his daughter, Maria Guadelupe Chew, places a plate with a crispy popover filled with pastry cream next to my cafe lechero. “Almost nobody makes those anymore.” I’m seated at the Chew family-run Café Allende in Mexico City’s vibrant Lagunilla neighborhood. Maria Guadelupe also handles the cafe's accounts, and on weekends, she brings her father from his home in the far northwest of the city to enjoy time at the cafe. The elder Chew, a local icon, warmly greets customers as they pass by the vintage cash register and settle at the Formica tables.

To those unfamiliar, the different varieties of pan chino may resemble other morning delights found throughout Mexico—such as pan dulce, conchas, panques, and flaky triangle pastries filled with apple or pineapple. However, one bite reveals a slightly denser, moister texture, accompanied by an almost imperceptible clash of salty and sweet. At Café Allende, Maria Guadelupe complements mine with a refill of cafe lechero, the traditional drink that typically comes in a retro soda glass with a long metal spoon.

At 80 years old, Jesus came to Mexico from the Canton region (now Guangdong) at the age of 15 to operate Café Allende. His father, Martín, who arrived in Mexico a few years earlier, bought the cafe in 1957. Like most cafes chinos of that era, it was a simple establishment catering to workers and students seeking an affordable coffee and a cheap plate of beans and eggs to satisfy their hunger. Today, the clientele mainly consists of nostalgic older patrons and a few families reminiscing, but the working-class essence remains strong.

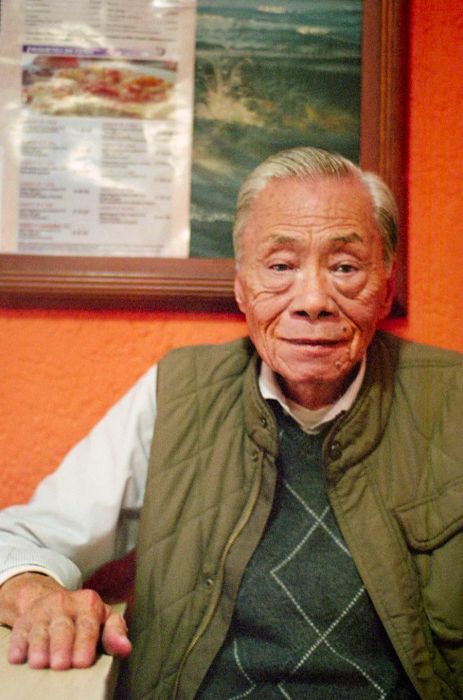

Jesús Chew has been the owner of Café Allende since 1957.

Jesús Chew has been the owner of Café Allende since 1957.Chew reminisces about a time when seven Chinese-owned cafes lined Ignacio Allende. “They were small establishments,” Jesus recalls. “Bread was sold for 20 centavos, and coffee cost just one peso.” Now, his cafe stands as the last of its kind.

In recent years, cafes chinos on Allende and beyond have been supplanted by trendy coffee shops and commercial chains like VIPS and Sanborns, which offer similar homestyle meals and inexpensive coffee in a diner-like setting. In some cases, these changes have occurred gradually, with many visitors to Mexico City dining in the original cafes chinos without even realizing it. La Pagoda and El Popular, two historic diners on Avenida 5 de Mayo, are still owned and run by Chinese immigrants.

Jesus’s father acquired Café Allende from another Cantonese immigrant, a common practice at the time as businesses often changed hands within the Chinese community. This solidarity was crucial during an era of heightened anti-Chinese sentiment, when informal lending and personal networks were often the only means for immigrants to establish their businesses.

Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, Chinese laborers were attracted to Mexico by job opportunities in railroads and agriculture. They were also compelled to leave due to the Chinese Exclusion Act enacted in the U.S. at the end of the 1800s, which increasingly restricted immigration over the following decades. After the 1910 Mexican Revolution, growing Mexican nationalism and social upheaval led to the scapegoating of immigrant groups. The Chinese community in northern Mexico faced severe violence during much of the early 20th century, prompting a mass migration to the capital, where conditions were less hostile and job opportunities were more abundant.

An assortment of pan chino at Café Allende (top left); a diner enjoys breakfast at Cafe Goya (top right); a club sandwich features prominently on Cafe Goya's menu (bottom left); the lively El Centro area, home to Cafe Goya (bottom right).

Cafes chinos originated with that wave of immigrants. Many of the few that remain still display traditional red paper lanterns from their eaves and bear signs in the vintage, albeit controversial, angular script associated with Chinese businesses of that time. At Cafe Lucky in the St. María de Ribera neighborhood, a small glass case holds a Buddha altar, accompanied by a photo montage of the owner's ancestors, illustrating a blend of first and second-generation Mexican-Chinese culture.

While most of these cafes now operate on limited hours, they once functioned around the clock, providing a friendly haven for both compatriots and locals. “The clientele was not upper class,” recalls Alfonso Chiu, who has worked in and owned several cafes chinos since arriving in Mexico as a child in 1959. “People would stop by in the morning, grab a boiled egg from the table, tap, tap, tap... order their coffee, and eat quickly.”

Pan chino was always available, though there are various theories regarding how these pastries became the quintessential Chinese Mexican treat. Jorge Chao Rodriguez, owner of the now-closed Restaurante La Nacional, noted in an interview that the Chinese learned baking from French masters, a sentiment echoed by Alfonso Chiu: “They learned from the French in China, either by working for French or English families, or in their bakeries,” he explains. “They brought that influence with them to Asia, adapting it along the way. It wasn’t exactly French bread; it evolved with different types of flour and water. The delightful biscuits we enjoy here emerged from this blending of influences.”

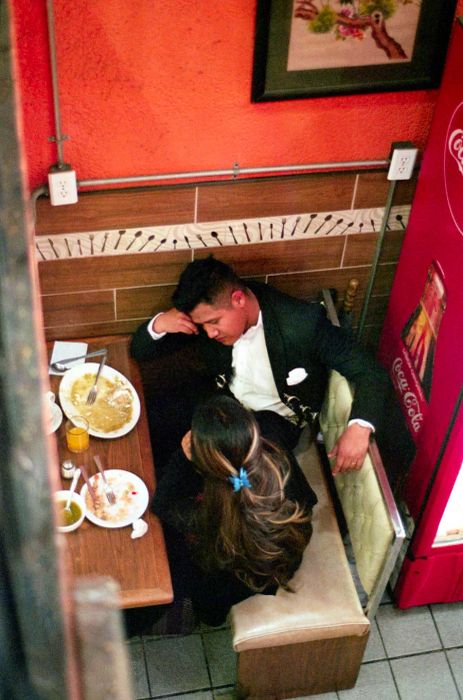

A young mariachi enjoying a date at Café Allende.

A young mariachi enjoying a date at Café Allende.Noted 20th-century author and food historian Salvador Novo offered a different perspective, suggesting that Chinese immigrants acquired their baking skills while working on the railroads during the 19th century; others believe they learned to bake in mining camps out west. Regardless of the origin, it’s evident that baking provided a job opportunity for newly arrived immigrants, and many excelled at it. “To make bread, you don’t need to speak,” explains Roberto Yip, son of Cafe Goya owner Sai Ping Wong, reflecting on the many Chinese immigrants who arrived in Mexico with little Spanish. “They could rely on their hands and their intellect.”

“They simply found something they wanted to create and figured out how to do it.” Roberto’s father worked as a baker at another establishment before he and Sai Ping Wong (affectionately known as Anita by her patrons) took over Cafe Goya from another immigrant in the mid-1960s. Until 1954, the area around Cafe Goya served as the vibrant center of Mexico’s National Autonomous University campus, bustling with students day and night, who would often skip class or drop by after a performance at the Goya ThMytour across the street. As a child, Roberto would spend his afternoons wandering in and out of the kitchen, enveloped in the aroma of freshly baked bread, filling the restaurant’s pitchers with cafe lechero for a few pesos.

“It’s been noted that the Chinese created that style of coffee in Veracruz,” says Luis Chiu, Alfonso’s son and head chef at the popular Asian Bay restaurant in Mexico City. “Since they drank tea with milk in Hong Kong, they understood it to be similar to condensed black tea mixed with milk.”

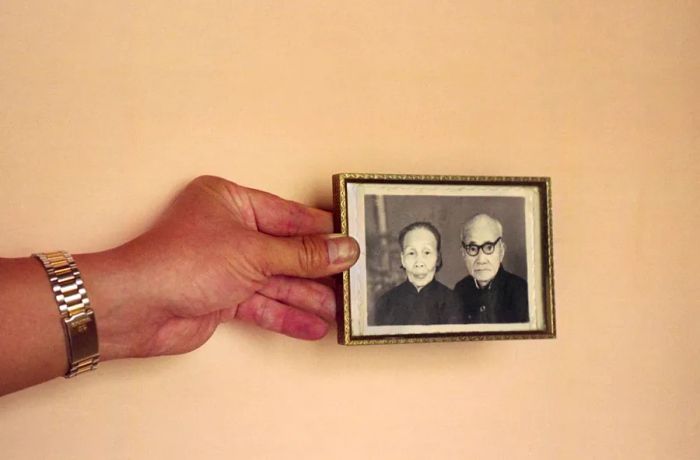

Sai Ping Wong, the proprietor of Cafe Goya, who relocated to Mexico in 1959 (top left); a wide array of bread available at Café Allende (top right); Roberto Yip Wong showcasing a photo of his grandparents (bottom left); a hearty breakfast served at Cafe La Pagoda (bottom right).

Today, many cafes from that era still serve a few Chinese dishes, offering some off-menu specialties for those longing for a taste of home—chow mein, chop suey, or basic fried rice—with varying quality and authenticity. However, in recent years, most Chinese options have vanished from menus, partly because the younger generation struggles to uphold the tradition. “There’s no one left to prepare them,” explains Roberto Hernandez, Jesus Chew’s brother-in-law who manages Café Allende. He often cooks his favorite Chinese meals with the elder Chew at home but finds it challenging to reintroduce them at the café. “You really need someone skilled in Chinese cooking.” Today, the most popular dishes at these cafes are straightforward Mexican favorites—chilaquiles, enfrijoladas, pechuga empanizada. Jesus Chew enjoys the beef soup at Café Allende, and Roberto Yip mentions that people travel from afar to enjoy the chilaquiles at Cafe Goya, served in a traditional low clay bowl.

While the number of these unique establishments has dwindled, their significance in Mexico City’s culinary landscape remains acknowledged. “It’s generational,” remarks Ruben Campos Molina, a long-time neighbor and frequent patron of Café Allende. “My mother took me there as a child, and now my grandson goes. More than just a tradition, it’s a necessity.”

Lydia Carey is a freelance writer residing in Mexico City and the author of Mexico City Streets: La Roma. Mallika Vora is a photographer based in Mexico City.

1

2

3

4

5

Evaluation :

5/5