The Modern French Corner Store: A Rustic Shopping Dream

On a recent Sunday just after noon, a Parisian in her forties rushed into Superfrais, a specialty grocery store in the 20th arrondissement, clearly on a mission. 'Salut les gars! I’m starving. Do you have any of that pizza left?' she asked eagerly. The pizza she referred to was a frozen personal-sized option from Louie Louie, a well-known restaurant in the 11th arrondissement owned by Alexis Poirson, who also started Superfrais. Unfortunately, Hortense, one of the employees, informed her that they had completely sold out midweek. 'We can’t keep them in stock! Come back next week; it’ll be waiting for you,' she assured her.

Out she went, and in came three regulars—one returning for his second espresso of the day, which he enjoyed on a wooden bench outside; another headed straight to the back to grab fresh produce for the week while browsing a cookbook or two in the bookshop nook. The third had a clear plan, starting at the spice and condiment shelf for vegetable dashi and Maison Martin’s hot sauce, moving on to the eco-friendly cleaning products, then to the wine and spirits corner for a bottle of Pierre Cotton’s Côte de Brouilly, and finally circling back to the counter for a custom-made sandwich filled with pistachio mortadella and lemon burrata for just 7 euros.

This scene unfolds like a modern take on the classic fantasy of French grocery shopping, where locals spend their days with wicker baskets, meandering between open-air markets and specialty shops. They take their time browsing and socializing, living out the stereotype that they understand the finer things in life: terroir, provenance, and first-name relationships with the fishmonger who sells the best line-caught dorade (not to mention vacation time). Despite the myth that France does food best, the nation has been drifting away from this artisan culture for decades. Yet the afternoon visitors at Superfrais embody the ideal, hitting all the marks promised by the store’s signage: cheese, coffee, natural wine, and—importantly—épicerie, a nearly extinct type of gourmet grocer where this shopping fantasy once thrived.

Exterior view of Superfrais.

Lindsey Tramuta

Exterior view of Superfrais.

Lindsey Tramuta Containers of dried goods at Superfrais.

Lindsey Tramuta

Containers of dried goods at Superfrais.

Lindsey TramutaThe concept of épicerie dates back to the Middle Ages, where it represented a small shop focused on spices sourced globally (with 'épices' translating to spices). As time progressed, other food items were incorporated, and shop owners began packaging their own goods with personal labels. By the late 19th century, a network of family-run, namesake shops had emerged throughout the country. However, traditional épiceries faced decline in the 20th century, overshadowed by large, self-service hypermarkets like Carrefour, which offered high-volume, low-cost essentials.

Superfrais seeks to rekindle that old tradition, encouraging shoppers to reconnect with their food culture in a more deliberate manner. It’s part of a wave of new épiceries emerging in urban areas, such as L’Epicerie Idéale in Marseille, Epicerie Sardine in Ciboure by the Basque coast, and 21 Paysans in Nice. These shops are also found in small towns, like L’Epicerie in the quiet village of Saoû, which serves as a minimart, but the new épiceries appear especially nostalgic and intentional within bustling cities.

“Upon moving to the neighborhood, I aimed to establish a food hub, inspired by traditional village épiceries that not only offered daily necessities but also served as a social gathering spot,” shares owner Poirson.

Traditionally, the caliber of an épicerie was largely determined by its owner, the épicier. These individuals were often brokers or importers with the skills and connections to source unique or specialty items,” notes Claire Pichon, editor-in-chief of the food magazines Fou de Cuisine and Fou de Pâtisserie. “Customers relied on their expertise and discerning taste, coming specifically for exceptional coffee, the finest canned sardines, and outstanding olive oil—items not found elsewhere.”

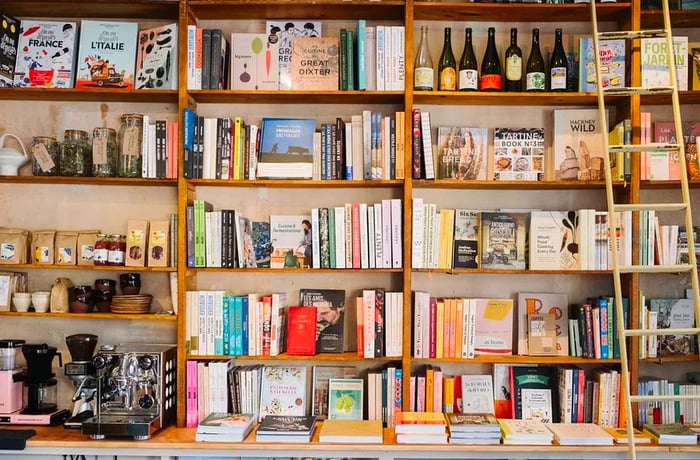

Bookshelves at Provisions.

Louise Skadhauge

Bookshelves at Provisions.

Louise SkadhaugeWhile it might be tempting to liken the resurgence of the épicerie to the growth of indie curated corner stores in the U.S., they stem from different traditions. Like épiceries, these stores offer expertise alongside food. However, American shops have primarily emerged from the digital realm, selling direct-to-consumer packaged goods that are easily accessible online. In contrast, the épicerie is rooted in brick-and-mortar history, attracting customers not through novelty or social media appeal, but by reviving regional culinary knowledge and fostering personal relationships with farmers and patrons that characterized past épiciers.

This is evident at Provisions, located about 500 miles south of Superfrais, in a working-class neighborhood of Marseille. The épicerie hosts fermentation workshops, book signings, and pop-up events with chefs, serving not just as an alternative to supermarkets but also as a space for learning and idea exchange. “We see ourselves as cultural transmitters, connecting producers within 150 kilometers [about 93 miles] to consumers,” says food writer Jill Cousin, who opened the shop less than a year ago with retail expert Saskia Porretta, as an extension of their monthly pop-up farmer’s market, Hors Champs, launched in 2020.

Their impressive range of nearly 2,000 products features spices from Shira, a label specializing in wild, organic, and rare spices sourced directly from producers; dried pasta from Paolo Petrilli in Puglia; premium teas from Le Parti du Thé, which prioritizes transparent and ethical sourcing; seasonal flowers cultivated in Arles; canned goods and condiments from local artisans; and some of the finest natural wines and ciders in the country. “I worry about our society’s digital-first approach, but I believe if people are offered accessible alternatives that don’t require detours, they’ll make different choices,” Cousin adds.

Provisions occupies the former site of a multilingual bookshop that operated from the 1950s until Cousin and Porretta discovered the space for rent in 2021. They preserved much of the original interior, including the towering wooden shelves, rolling library ladder, and vintage floor tiles. The rustic cabinet of curiosities aesthetic is intentional. To attract local residents of all ages and budgets, particularly the large community of retirees on modest pensions, the design needed to evoke a sense of familiarity and comfort; this old-world charm stands out against the contemporary Scandi-inspired setups of many trendy shops targeting younger customers.

While they do offer some higher-priced items like smoked fish, soy sauce from Touraine, and cookbooks priced between 30 to 40 euros, inclusive pricing is a cornerstone of their vision. “There’s a woman who visits weekly just to buy a single flower because she can’t afford more, but after learning that 80 percent of flowers sold in France come from far away, she understands it’s a better choice no matter how many she buys,” explains Porretta.

Inside Provisions.

Louise Skadhauge

Inside Provisions.

Louise SkadhaugeThe superstores that once drove traditional épiceries into decline are now facing significant downturns. Philippe Moati, co-founder of the Observatoire Société et Consommation, suggests this shift is a response to the dehumanization of commerce. He mentions in the documentary Hypermarchés: la Chute de L’Empire (Hypermarkets: Fall of the Empire) that these stores are increasingly linked to overconsumption and excess, which society is increasingly rejecting due to heightened awareness of environmental issues. This growing awareness—whether viewed as a backlash against mass consumption, a realization of the disconnection from food sources, or a reaction to the monotony of modern shopping—has helped stimulate the revival of the épicerie.

“There’s certainly a sense of nostalgia for rural life intertwined with this [resurgence],” says Mathieu Magnaudeix, an author and journalist for Mediapart. “It embodies the idea of proximity and reconnecting with a community, reminiscent of life in a small village, even within a big city.”

While urban dwellers may be opting for corner stores over Carrefour, this offers little comfort to small-town residents who have lost the very shops that inspired these new urban counterparts. Magnaudeix recalls fondly the regulars at his grandparents’ bustling épicerie, located across from the Périgueux train station in the Dordogne from the late 1950s until their retirement in 1992. Nowadays, many businesses in that town of 30,000 have either closed their doors or are struggling to survive, with his grandparents’ épicerie having become a Hertz car rental office.

The 2008 global financial crisis severely impacted the rural economy, leaving many main streets deserted. Rather than supporting small businesses, local leaders invested in one-stop shops and modern shopping centers on the outskirts. The few specialty shops that survived in the aftermath of the economic downturn are miraculous exceptions, and access to quality produce and ingredients remains limited in many areas.

Small and medium-sized towns are in dire need of an épicerie revival just as much as major cities. Ironically, they have begun to experience this since the COVID-19 pandemic, which led to the closure of many small businesses. In recent years, the government deemed certain traditional food shops essential, allowing them to remain open during lengthy lockdowns, thereby enabling residents to rediscover their significance and value.

The window display at Provisions.

Louise Skadhauge

The window display at Provisions.

Louise SkadhaugeHowever, the growing épicerie movement faces challenges as supermarket chains like Monoprix and Franprix adapt their strategies to include locally made and small-batch products, ranging from craft beer to specialty mustards, and even café-style seating for enjoying ready-made meals. Pichon warns that some establishments claiming to be épiceries may actually source their products from Rungis, the world's largest food market wholesaler near Paris. “If you stroll into any random épicerie in Paris, Strasbourg, or Metz without prior research, you might encounter the same olive oil, the same tea, and the same canned fish,” she states. France is also experiencing a rise in digital commerce; while online food shopping is still relatively low at 8.9 percent of food retail sales compared to the U.S., it is on the rise and expected to exceed 10 percent by 2023, according to data from Kantar.

The resurgence of épiceries represents not just a rejection of modern shopping habits and a nod to the past, but also the creation of a new future—a part of a broader cultural recalibration in France over the last decade. A wave of innovative entrepreneurs has confronted unprecedented challenges and the decline of traditional trades. They’ve come to understand that large corporations won't lead the change they promised, can't safeguard French manufacturing, and won't reduce excessive consumption and waste for the planet's sake. This frustration has sparked significant career shifts in fashion, design, and food, with individuals leaving corporate jobs to become cheesemongers and farm-to-table chefs—often drawing inspiration from the past to envision the future. Revitalizing these shops acknowledges the historical role of épiceries in French food culture and suggests they can once again become vital components of both small-town and urban social life—one artisanal pizza or flower at a time.

Lindsey Tramuta is a culture and travel journalist based in Paris, known for her works including The New Paris and The New Parisienne: The Women & Ideas Shaping Paris.

1

2

3

4

5

Evaluation :

5/5