The Rise of Deep-Sea Tourism: But Is It Safe?

As you dive underwater in a submersible, beams of sunlight flicker through the waves against the viewport. This initial glow fades quickly. As the sub begins its descent, the light shifts to blue, and as it goes deeper, all colors but blue start to vanish. Before long, the water transforms into a dark cobalt hue. A few hundred feet below, this blue dulls into a grayish indigo. Author Susan Casey, during her first dive, described this unique color—the only wavelength capable of penetrating such depths—as a “pure ultramarine,” almost intoxicating. Descending another thousand feet plunges you into complete darkness.

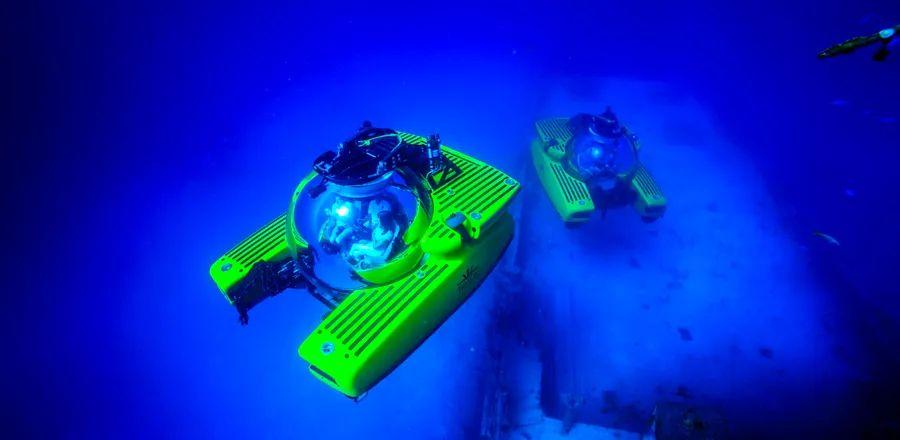

In the ocean's twilight zone, the first layer classified as deep sea, sunlight is nearly absent. The submersible's LED lights illuminate an alien landscape. Many species here predate the dinosaurs. Gill sharks, existing for nearly 400 million years, glide past. At certain depths, red-light wavelengths disappear, rendering red fish invisible or leaving them white. Some appear shiny, resembling floating mirrors. The shapes and movements of these creatures challenge conventional ideas of what animals can be.

“Why have we overlooked so much of the deep ocean for so long? It’s like living in a mansion filled with treasures and remarkable creatures, yet ignoring most of the rooms,” Casey writes in her August 2023 book, The Underworld: Journeys to the Depths of the Ocean. “This is a failure of curiosity, a kind of myopic oversight that leaves us strangely unfamiliar with our own home.”

The deep sea is a vast ecosystem that encompasses the majority of the planet's volume, yet for most people, it remains nearly unreachable due to the scarcity of vessels capable of deep-sea exploration that accept passengers. As you dive deeper, access to the ocean diminishes; fewer individuals have reached the deepest points of the ocean than those who have traveled to the International Space Station. Submersibles capable of such depths are primarily used for commercial purposes (like oil industry operations) or scientific research, with a few luxury crafts available for the affluent. Deep-sea tourism companies exist, but they often operate in legal gray areas, requiring travelers to carefully evaluate safety standards and their personal tolerance for risk.

For those who embark on this underwater journey, the experience can be transformative, shifting their understanding of the world's composition in ways often likened to an astronaut’s view of Earth from orbit. The deep sea is as otherworldly as space, yet it remains closer, stranger than the moon but intrinsically tied to our planet. “It’s not space. It’s vibrantly alive,” Casey explains. “When you consider the cultural importance we place on exploring outer space, here we have this inner realm brimming with life. That’s profoundly impactful. It broadens your perspective of Earth.”

Deep-sea exploration has always been a rarity. The first working submarine is believed to have been created by Cornelius Drebbel in the 17th century for navigation beneath the Thames in London. However, it wasn’t until three centuries later that technology significantly advanced for military and scientific purposes. Submarines and submersibles—with the latter typically needing to be transported long distances by another vessel and primarily designed for descent—have always been linked to exploration, but it wasn’t until 1960 that explorers reached the ocean’s deepest point. Using a bathyscaphe, a type of submersible, they descended over 35,000 feet to the Mariana Trench. This achievement wasn’t matched until 2012, when filmmaker James Cameron made his own descent in a submersible known as the Deepsea Challenger.

Since that landmark dive, there have been 20 additional crewed descents to the Mariana Trench, including Victor Vescovo’s Five Deeps Expedition, where he explored the deepest points in all five oceans from December 2018 to September 2019. Although the trench remains elusive for many, private submersible experiences are available for almost any determined and wealthy traveler, with numerous initiatives aiming to make the ocean more accessible through innovative means. In 2019, Uber launched a submersible rideshare to explore the Great Barrier Reef. One company in Vietnam offers submersible excursions for 24 people at once, diving to several hundred feet beneath the surface, while others provide 100-foot-deep submarine trips in locations such as Hawai‘i and Cozumel, Mexico.

None of these methods actually reach the deep sea, which begins at depths of over 600 feet, or even come close to it. In some respects, they might be more comparable to scuba diving (which typically doesn’t exceed around 120 feet below the surface). Beyond the twilight zone, which starts at approximately 3,300 feet, the ocean becomes completely dark, known as the midnight zone, and after 13,100 feet, it transitions into the abyssal zone. While accessing the deep sea is unique, entering the twilight zone can serve as an introduction to an otherworldly environment. “I refer to it as the Manhattan of the deep because it’s teeming with life,” Casey remarks. “This zone boasts more marine species than all other ocean regions combined, with about 80 percent capable of bioluminescence. It’s a dazzling, twinkling metropolis of creatures.”

However, options for travelers to access the twilight zone are limited. One such option is Scott Waters, who operates a submarine company in Tenerife, Spain. He takes individuals who contribute to scientific projects down to the depths. Waters collaborates with the Spanish Oceanographic Institution in the Canary Islands and tailors trips based on the project and budget—such as a dive near Tenerife for microplastics research costing about $1,955, while pricier excursions, like studying climate change in Antarctica or the origins of life at hydrothermal vents, can reach up to $54,000. (Waters states: “Those wanting to journey in a submarine are adventurers and explorers aiming to make a genuine impact on science.”) There’s also an unconventional pilot named Karl Stanley in Honduras, who constructed his own sub to take people to depths of around 2,000 feet. Alternatively, individuals can purchase a private submersible from Triton Submarines in Florida or Norwegian company U-Boat Worx, storing it on a yacht for use. Additionally, there was OceanGate, which ceased operations following its tragic implosion during a trip to the Titanic wreck in June 2023, resulting in the loss of executive Stockton Rush and four passengers.

Before its submersible went missing, OceanGate was arguably the most prominent deep-sea tourism company, celebrated for its innovative technology and Stockton Rush’s forward-thinking approach. The community of submersible enthusiasts is tightly knit, and they expressed concerns about such a disaster even before it was determined that the missing vessel likely imploded. Stanley had raised alarms about OceanGate’s technology after descending with Rush in 2018, and reports from Vanity Fair, The New Yorker, and CNN indicated that several other experts had voiced their worries prior to the incident.

The issue, according to Patrick Lahey, cofounder of Triton Submarines, was that Rush declined to submit OceanGate's submersibles for classification. There are several independent, international marine classification organizations that evaluate and ensure a vessel's safety for its intended depths, including agencies like Det Norske Veritas (DNV), which inspected and certified Vescovo’s sub. Achieving classification for a sub involves a rigorous process of multiple tests in pressure chambers and dives to depths beyond what it will encounter. Due to the complexity and the limited infrastructure available for certain tests (the only pressure chamber large enough for Vescovo’s sub was located in Russia), this process can become quite costly. Additionally, maintaining classification requires ongoing testing over time; it’s insufficient to be classified just once.

Technically, most submersibles do not fall under traditional maritime law since they do not depart from and return to ports—they are transported on another vessel. Consequently, they are governed by the laws of the jurisdiction in which they operate, creating complexities once they venture 12 miles from the coast into international waters. Insurance providers typically refuse coverage for vessels lacking independent classification, but this remains largely optional. For those subs that are classified and undergo rigorous testing and regular evaluations, their safety record is exceptionally robust. “The safety protocols are inviolable. They are sacrosanct,” Casey states. “They form the foundation of everything and always have.”

Many submarines are constructed from steel, like Stanley’s, or more frequently, titanium. They can be designed with either a single or double hull, feature ballast tanks that utilize water and air to manage buoyancy, and are often built in a circular or cylindrical shape to effectively distribute pressure across the structure. Subs intended for the ocean floor must endure pressures that can reach 15,750 pounds per square inch (PSI); in contrast, the pressure at sea level is 14.7 PSI. “To me, they are truly magical machines,” Lahey remarks, having built the titanium submersible that took Vescovo to the deepest points in all five oceans.

However, OceanGate was employing a new technology featuring a carbon fiber hull. The company asserted that its technology was so advanced and its safety measures so thorough that they surpassed any certification process requirements. “The OceanGate sub was an experimental craft, an anomaly. It did not undergo peer review,” Lahey explains, having constructed two dozen vessels for private clients, priced between $2 million and $50 million. He emphasizes the need for certification to be mandatory for continued human exploration in the deep sea. “I dislike the notion that individuals will fear diving in a sub because of that anomaly.”

Like many adventurers, those who descend to the deep sea must place their trust in the systems that support them. The OceanGate tragedy highlighted the risks associated with relying on an untested vessel, but with few regulations governing deep sea tourism, individuals eager to explore the depths must exercise their own judgment. Waters’s and Lahey’s subs are classified, as are all submersibles operating under U.S. jurisdiction, for example. In contrast, Stanley, who has conducted hundreds of safe dives, lacks classification. He explains that he chose not to pursue certification because it would have significantly inflated the cost of constructing his sub. “However, it’s all about applying common sense, thorough testing, due diligence, and maintaining a solid track record,” he asserts.

Stanley’s Idabel submersible departs from Roatán, an island in Honduras. Idabel is Stanley’s second sub; he started building his first one at age 15 in his parents’ backyard in New Jersey. He brought that sub to college in Florida, and after graduating, he showcased it at a dive show where he met a resort owner in Honduras who encouraged him to start taking tourists underwater. Over the past twenty years, he has completed more than 2,500 dives, typically taking three or four passengers to the deep sea for $1,200 an hour on trips lasting around four hours.

When he first began, Stanley shared that his passengers were primarily scuba divers eager to explore deeper depths. Now, he caters to engineers from companies like Google and Facebook who have the means to pursue extraordinary experiences. “If you have the chance to witness the most stable and expansive ecosystem on our planet, which comprises 90 percent of Earth’s living space, why wouldn’t you?” Stanley remarked.

A few weeks following the OceanGate incident, a YouTube travel vlogger named Ace, who has about 482,000 subscribers, visited Stanley in Honduras for an underwater adventure. He recorded his descent while seated by the large window. In the video, he converses with Stanley, posing questions about the submersible. He also sends greetings to his family and listens to Stanley’s tales about the longest underwater durations. At one of the dive’s deepest points, as the sub hovers over a neon-lit rock formation, he marvels at the unusual scenery. “Wow. Wow. That’s amazing. Wow. Beautiful,” he exclaims, and they share a moment of silence, taking in the depth around them.

1

2

3

4

5

Evaluation :

5/5