The Teriyaki Tycoon

When you ask Seattle locals to describe the city’s unique take on teriyaki, they might mention the nostalgic sound of a Styrofoam container — a remnant of the past — the sweet sauce that coats the crunchy salads, and the rice so well-prepared it was highlighted in John Hinterberger’s 1976 review of the pioneering Toshi’s Teriyaki Grill. Yet, the person behind most of Seattle’s teriyaki remains a lesser-known figure.

Seattle’s distinctive fast food, which bears only a linguistic resemblance to the traditional Japanese dish, grew from the original Toshi’s Teriyaki Grill, spreading rapidly across the city in the ’90s, and is now facing a decline — a trend I explored in Thrillist in 2016. “Teriyaki Takes the Town — Everybody’s Making It,” proclaimed the Seattle Times in 1992. Jonathan Kauffman later described it as “Seattle’s Own Fast-Food Phenomenon” in 2007 for the Seattle Weekly. “You can find it in almost any strip mall,” he wrote, noting the eclectic menu: “A mix of teriyaki, spicy beef, yakisoba, and bibimbap, among other dishes.” This variety offers a glimpse into the untold story behind Seattle’s teriyaki legacy.

Though Seattle’s iconic teriyaki — featuring charbroiled chicken thighs in a sweet soy sauce — is widely believed to be inspired by Japanese cuisine and created by Japanese immigrant Toshi Kasahara, the presence of bibimbap — a Korean dish — suggests that many of Seattle’s teriyaki shops are actually run by Korean immigrants.

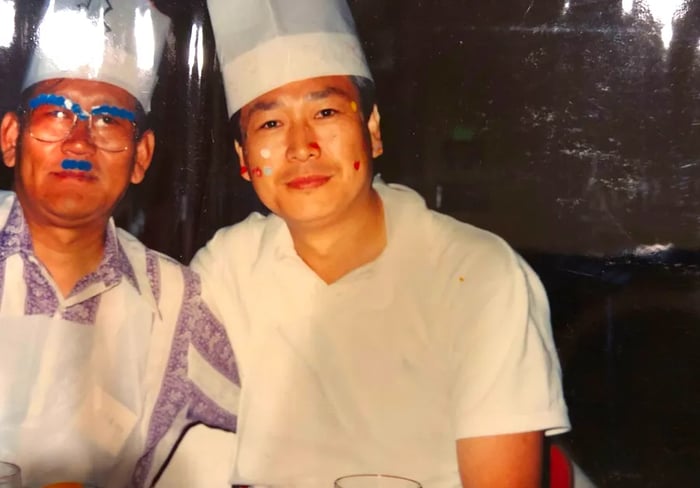

John Chung and a church friend taking a break from cooking teriyaki.

Chung Family

John Chung and a church friend taking a break from cooking teriyaki.

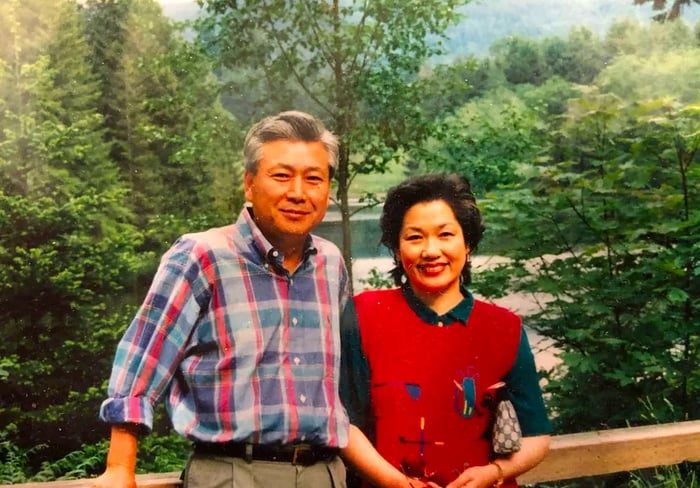

Chung Family John and June Chung in the early 1980s, shortly before relocating from Los Angeles to Seattle.

Chung Family

John and June Chung in the early 1980s, shortly before relocating from Los Angeles to Seattle.

Chung FamilyWhen John Chung arrived in Seattle in 1983, he was unaware of Kasahara’s teriyaki shop, which had already expanded to a second Green Lake location. However, Chung had previously experimented with a style he referred to as teriyaki in Los Angeles — a style quite different from Kasahara’s. While Kasahara’s teriyaki featured slow-cooked chicken thighs, Chung’s version was designed for quick service, using thinly sliced, marinated meat that was often served on sandwiches rather than over Kasahara’s meticulously prepared rice. Over the years, Chung opened and sold several teriyaki shops, training over a hundred Korean immigrants in the process. Seattle’s teriyaki evolved into a unique genre, described by the New York Times in 2010 as “Japanese in name only,” yet predominantly Korean-owned. Despite the recognition of Korean ownership in various articles, the underlying reason for this trend has remained unexplored — until now, with John Chung’s story at the center of it.

Just out of the military and recently married, John Chung honed his cooking skills during a six-month stint at a Korean culinary school. His brother-in-law in America planned to open a restaurant, so Chung trained to assist before emigrating. However, it was not this training but a two-hour layover at Sea-Tac while relocating to New York in 1977 that truly altered Chung’s trajectory. Gazing out at the city, he thought, ‘This is a beautiful place. It’s where children should grow up.’

The quintessential teriyaki plate featuring chicken, rice, and salad

The quintessential teriyaki plate featuring chicken, rice, and saladChung and his wife June relocated to California and purchased a former pizza joint in Cerritos. Over two weeks, they removed plastic grapes from the ceiling and revamped it into C & C Teriyaki, marking Chung’s initial entry into the teriyaki scene. “I came across the term in a Japanese magazine,” Chung explains, noting that his creation was akin to Korean bulgogi rather than traditional teriyaki.

Their first venture was a disappointment. “Nobody had a clue what it was,” Sylvia Kim, Chung’s daughter, recalls about their 1979 opening. The food wasn’t great either. “We ended up singing hymns to pass the time,” Chung remembers. They eventually sold the place and launched a second, much more successful establishment — Magic Sandwich — where Chung innovated by serving teriyaki on bread.

However, a new challenge emerged: Chung and June observed that the children of local immigrants were falling into trouble — gangs, drugs, and other undesirable paths. With their business thriving, Chung found a buyer quickly. By July 1983, they packed up and drove to Seattle with no friends, plans, jobs, or homes lined up. But they did bring Chung’s teriyaki recipes along.

Founded by Russian émigré Joseph Zhovtis, Elo’s Philly Grill, a mini-chain in the Seattle area, was named after Zhovtis’s brother who was imprisoned in the Soviet Union. By November 1983, just before Chung acquired the Kent location, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer reported that Zhovtis faced difficulties keeping his Kirkland and Lynnwood outlets in business due to negative sentiments towards the Soviet Union, which had recently downed a Korean Air Lines plane. This was a sensitive period as Korean immigrants were settling heavily in the U.S., particularly in the Pacific Northwest.

Beginning in 1965, U.S. immigration laws shifted away from targeting Asians, leading to a surge of Korean immigrants. Between 1965 and 2001, over 800,000 Koreans arrived in the U.S. The Korean population in Seattle went from just 712 in King County in 1970 (mostly students at the University of Washington) to nearly 13,000 by 1990. In 1983, the same year the Chungs and their children, Sylvia and Howard, arrived, the city celebrated Korea Day with a prayer breakfast for leaders of the area’s 24 Korean churches — vital community hubs and significant influences in the Chungs’ lives.

At Elo’s, Chung revamped the menu from Zhovtis’s offerings to his own creations, including a popular spicy barbecue pork sandwich. The demand was high, leading him to expand next door to accommodate more seating. Despite Chung’s culinary prowess, he never missed a chance to capitalize on success. “When business is booming,” he notes, “Koreans are keen to buy it.”

In Los Angeles, Chung observed other Korean family businesses, but upon arriving in Seattle, he found many Koreans had been employed at Lockheed Shipyard, which faced several layoffs before closing in 1988. Many of these immigrants had some savings and a desire to start their own businesses. The 1980 census revealed Koreans had the highest self-employment rate, almost double the general population. This available market of potential buyers allowed Chung to sell Elo’s at a good profit and treat his wife to a trip back to Korea.

Upon returning, they used their profits to start from scratch with Woks Deli and Teriyaki in Georgetown. The shop was ideal for Chung’s plan: a small, weekday lunch spot in an industrial area filled with workers. Even before the kitchen was complete, local workers were already inquiring about the opening. “From day one, there was a line out the door,” Chung recalls. June Chung, who manned the cash registers, often complained about her sore hand at the end of the day. This marked the beginning of Chung’s journey as a teriyaki pioneer.

“In the diverse culinary landscape of Georgetown, where else could you find teriyaki beef or chicken and a Philly cheese-steak sandwich under one roof?” asked Seattle Times writer Tom Phalen in 1992 about Woks Deli. Though the review came after the Chungs had sold it, it highlights their influence on the menu. “You could even get a teriyaki cheese-steak sandwich, along with barbecue beef and pork, ham and cheese, the Woks’ Magic Sub, and Sukiyaki Beef on rice.”

Chung’s teriyaki recipes began with a marinade of garlic, soy sauce, sugar, ginger, wine, and lemon juice. The trick was to make the marinade fresh daily and then let the meat soak for two to three days in the cooler. When it was time to cook, he knew what mattered most to his customers: their time.

John Chung not only shared his business acumen with his community but also transformed the Seattle teriyaki scene.

John Chung not only shared his business acumen with his community but also transformed the Seattle teriyaki scene.Charbroiling isn't practical for lunch due to the time it takes. Instead, Chung prepped the chicken thighs by removing bones and fat, slicing them before marinating so they would cook quickly once ordered. For beef, he opted for large, inexpensive chuck roasts and sliced them in the style of bulgogi.

The actual cooking process took just under five minutes. Chung’s spiciest creation, a pork dish enhanced with Korean pepper paste and chili powder, remains his pride and joy. He believes that any Korean teriyaki shop featuring this dish is a descendant of his influence — either directly from his teaching or through one of the many individuals who worked for free at his shop to learn his secrets.

“When you open that Styrofoam container, and the steam rises, revealing the glossy, caramelized sauce, fresh green onions, and steamed cabbage with mushrooms mixed in, that’s when you know,” describes Sylvia Kim. Howard Chung adds that the sauce’s unique consistency, similar to real maple syrup — dark, runny, yet thick — sets it apart from others.

A few years ago, Chung estimated that nearly all teriyaki shops in Seattle were Korean-owned. “That all started with me.” During this period, other Koreans in the community, inspired by Chung’s success, sought to replicate it. The church played a key role in this network — everyone attended the same churches, says Howard, “even if you weren’t Christian.” It wasn’t a specific influence that spread teriyaki throughout Seattle, but rather the Korean church community.

“People came to me eager to learn teriyaki,” Chung recalls. “But my style is different.” While Kasahara’s version, which had become widespread, had a vaguely Japanese flair, Chung’s approach was uniquely his own. “Working people don’t have time,” he noted, contrasting with Kasahara’s more time-consuming methods. “That’s why I developed teriyaki for the grill.” Patrons could watch the meat cook quickly in his open kitchen, served almost immediately over rice or in a roll. With lunch and a beer costing around $10, they were generating $1,500 daily — and they weren't even open very long each day.

During those few hours of operation, there was often an extra hand in the kitchen, sometimes from church or a neighbor. Former shipyard workers looking for new opportunities would come in and learn from Chung. “They picked up skills from me,” says Chung. He can often trace new restaurant openings back to these apprentices: for instance, after teaching the owner of Happy Donut, it soon transformed into Happy Teriyaki. “I’m open, I teach them everything.” People visited his shop to learn his sauce and fast-cooking techniques for chicken.

Cooking was a straightforward skill to acquire. Apprentices would stay for a few weeks, learn the essentials, and then move to different neighborhoods to start their own businesses. “It was like a cycle,” Kim reflects, echoing Chung’s own pattern: open a business, succeed, sell it to someone else, and start a new venture.

After selling Woks Deli & Teriyaki, the Chungs opened a new shop in Redmond, but it didn't attract the same support as their Seattle Georgetown location. John Chung sold it to another Korean aspiring teriyaki entrepreneur in 1988 and embarked on a mission to South America with the church. Upon his return, June acquired a bakery, Chez Dominique, and it seemed their teriyaki days were over. However, a few years later, a new opportunity across the street revived their business with John’s Wok on Western. John later attempted ventures in Aspen and Seattle, including Zeena’s in 1998 and a second John’s Wok in Mukilteo. Despite struggling, June eventually succeeded in real estate with Howard, and she discovered the closing of a Thai restaurant in Pike Place Market, an ideal spot for a new teriyaki venture.

Chung’s last establishment was a respected booth in Pike Place Market called Market Galbee. Though it featured a more traditional Korean menu, his sandwiches, particularly the spicy pork, onions, and mozzarella cheese on a French roll, received rave reviews. By 2015, the Chungs felt it was time to retire. After eight years of grueling hours, Chung needed knee surgery and a way out. Their prayers were answered by Gerry Kingen, founder of Red Robin and Salty’s, who took over the Market booth and rebranded it as Pike’s Pit. Kim, inspired by this change, bought the franchise rights to Pecos locations for northwestern Washington, while still dreaming of future ventures.

“Our parents hoped we wouldn’t end up in small business,” Kim says. The first generation started restaurants out of necessity and hoped their children would become doctors or lawyers. “They didn’t want us to go through that.” Now, the second generation sees value in pursuing the American dream their parents sought. Kim cites David Chang of Momofuku, and Howard Chung points to local entrepreneurs like Jason Koh of Japonessa and Peter Pak of Oma Bap as inspirations.

The Chung family, from left to right: Howard, June, John, and Sylvia Kim.

The Chung family, from left to right: Howard, June, John, and Sylvia Kim.Today, Howard Chung is with John L. Scott Real Estate, and Kim holds the Pecos franchise rights. Yet, teriyaki is deeply ingrained in their heritage. Whenever the topic of owning teriyaki shops arises, their drive to honor their father's legacy is unmistakable. Kim believes there’s potential to reinvent their father’s beloved teriyaki for a modern audience. “I think there’s still space to showcase dad’s teriyaki in a fresh way, incorporating the best of what he created,” Kim reflects. While their father focused on providing for the family, she envisions perfecting the cherished recipes into a contemporary business.

They all agree that there’s no place nearby that matches Chung’s teriyaki. Although they still enjoy local teriyaki spots, none measure up to what their father achieved. “It would be amazing if teriyaki wasn’t fading away,” Howard Chung muses. “Perhaps it’s just in a temporary lull.” Having witnessed its evolution and their father’s role in popularizing it across the city, they are determined not to let it disappear. Even John Chung himself remains open to possibilities. “I’m too old right now,” he jokes. “I don’t know, Dad,” Kim responds, and everyone laughs. Yet Chung admits, “Maybe Sylvia could start a business, and I could assist. I have plenty of ideas.”

For now, the family is content sharing their story and preserving their patriarch’s legacy from a time before food blogs and Instagram captured every detail of small businesses. Chung, who once served thousands with his recipes and helped a community thrive in a new country, now cooks for a much smaller audience. His wife, June, has been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, and he has taken on the role of her caretaker. “I cooked for 40 years; now I prepare three meals a day for my wife,” Chung says. “This is my job now.”

Naomi Tomky is an acclaimed food and travel writer and the world’s most enthusiastic Dinogo of everything. Her debut cookbook is set to release in November.Lauren Segal is a freelance photographer based in Seattle.Edited by Rafe Bartholomew

1

2

3

4

5

Evaluation :

5/5