The UK is aiming to construct one of the world’s most groundbreaking bridges

On the westernmost edge of Europe, two small islands with a complex history are situated.

Ireland and Britain are separated by just 12 miles at the narrowest point of the Irish Sea, but the waters here hold deep significance in many ways.

For over a century, the northeastern part of Ireland has been under the governance of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

In an effort to enhance domestic transportation, the UK government is conducting a feasibility study to explore the possibility of connecting Northern Ireland to Scotland via a bridge or tunnel, with results expected later this summer.

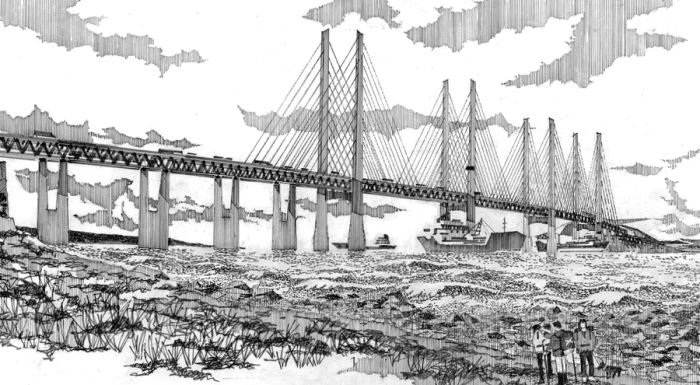

The concept isn't new, but it has gained momentum since 2018, when UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson expressed his support, and Scottish architect Alan Dunlop presented his vision for a rail-and-road bridge connecting Portpatrick in Scotland to Larne in Northern Ireland.

More recently, the so-called 'sausage wars' between the EU and the UK over trade disruptions caused by Brexit have given new urgency to finding a smoother route across the water.

While the distances are relatively short, the geological and environmental challenges are vast, making this one of the most technically demanding engineering projects in history. Economic, infrastructural, and political concerns also complicate the proposal.

Westminster’s plans have been met with skepticism by local leaders, with Scotland’s First Minister Nicola Sturgeon calling it a distraction from more pressing issues, while Northern Ireland’s Sinn Féin Deputy Leader Michelle O’Neill referred to it as a 'pipe dream bridge.'

Once isolated on the European continent, the UK has earned a reputation for burning bridges rather than building them. Yet, if this project succeeds, it could become a marvel on par with the Golden Gate Bridge or the Channel Tunnel. The key question for the forthcoming report is: Can a permanent sea link be realized—and is it truly worth it?

A bridge over troubled waters

The striking geology of this region is showcased in the Giant's Causeway, a UNESCO World Heritage site in Northern Ireland, and its Scottish counterpart, Fingal's Cave. Legend has it that these lands were once connected by a bridge formed from the same basalt columns, created by ancient volcanic eruptions.

Beneath the surface of this narrow stretch of sea lies Beaufort’s Dyke, a vast 50-kilometer trench carved during the last Ice Age. While its average depth is about 150 meters, the trench plunges to over twice that in some places—deep enough to submerge the Eiffel Tower.

This trench sits directly on the most straightforward route between Scotland and Ireland, and it also happens to be the largest known military dump in the UK. Over a million tons of unexploded munitions, along with chemical weapons and radioactive waste, were disposed of by the UK Ministry of Defence between World War II and the mid-1970s.

In addition to this, the area is plagued by rough seas, powerful currents, and the notoriously unpredictable weather of both Ireland and Scotland. The presence of munitions poses the first major hurdle to the proposed sea link project.

The clearance operation

It’s described as 'a monumental clearance effort,' according to David Welch, managing director of bomb disposal specialists Ramora UK. 'It’s not impossible, but it’s going to be incredibly difficult,' he adds.

He likens the challenge to recovering the most iconic artifact from Northern Ireland’s shipbuilding legacy: 'It’s somewhat like trying to raise the Titanic.'

In a typical offshore project, clearance teams may deal with between one and ten large munitions each day. As a result, the cost of clearing the trench could run into 'many, many millions of pounds' before any construction work could even begin.

'The currents in this area are extremely strong,' explains Margaret Stewart, a marine geoscientist from the British Geological Survey. The exact locations of the munitions remain uncertain, as many have drifted north along the seabed, while others were dumped prematurely by crews cutting corners.

For a bridge or tunnel to be built, says Welch, 'You must be certain that the area where you're planning to place equipment, assets, or personnel is thoroughly cleared to safely position the vessels and conduct all necessary work.'

'What you don’t want is to clear an area around the bridge, only to have munitions that were moved over time end up near the bridge’s base,' he adds.

Getting from point A to point B

Building a bridge or tunnel isn’t just about drawing a line between the two nearest land masses, says Paul Quigley, a geotechnical engineer and director at Gavin & Doherty Geosolutions in Ireland. The sea is far from a blank canvas.

'There’s existing infrastructure to consider, including cables and shipping lanes,' Quigley points out. 'When you start mapping the seabed, you realize how limited and constrained the available resources really are.'

On land, you also have to take into account the condition of roads and rail links, as well as the distances to major population centers. While Torr Head in Northern Ireland and the Mull of Kintyre in Scotland are the closest points, they are still remote from the key cities of Belfast, Derry, Glasgow, and Edinburgh.

The largest cities on the islands—Dublin in the Republic of Ireland and London in southeast England—are even further apart.

Three ferry routes currently connect the two islands. The Larne to Stranraer service links Northern Ireland and Scotland, but due to its distance from major hubs, it is less frequented than the busier Dublin to Holyhead route in Wales.

According to Quigley, 'Brexit has highlighted the significant trade flow into Dublin from Britain, much of which is destined for Northern Ireland.' He believes it would be difficult to convince stakeholders to invest in a route that diverts traffic so far north, especially when ferry options are already well-established.

'It’s good to dream and imagine these possibilities,' he says, 'but there has to be a real need for the project.'

Celtic Crossing

'No major infrastructure project has ever been free from criticism,' architect Alan Dunlop tells Dinogo.

Dunlop has studied recent bridge, tunnel, highway, and oil rig projects across the globe, all built in similarly challenging geological environments. While he acknowledges that 'none of these projects are as difficult as this one,' he firmly believes that 'the United Kingdom has the engineering and architectural expertise to take on such a task.'

His design proposes a 45-kilometer floating pontoon-style bridge anchored to the seabed by cables. Inspired by oil rigs in the Gulf of Mexico, which are anchored at depths of up to 1,000 meters, his concept aims to tackle similar challenges.

Its groundbreaking designs feature floating bridges supported by pontoons—an innovative solution for dealing with extreme depths that eliminates the need for columns to touch the seabed—and the world’s first 'floating tunnel.'

A submerged 'floating tunnel'—a tube suspended by pontoons or anchored to the seabed—could be paired with a bridge as part of several design proposals currently under consideration.

Record-breaking bridges

For the Irish Sea project, 'You’re pushing the limits of what’s possible with current bridge technology,' says Quigley.

'The main limitation for the bridge is the weather conditions. There will be times when high winds force the bridge to close for safety reasons. Additionally, building in such a harsh environment means the bridge’s maintenance could be prohibitively expensive,' he adds.

Although a multi-span suspension or cable-stayed bridge could be feasible, traditional tower supports would need to reach unprecedented heights on the seabed, meaning more innovative solutions would be necessary.

China currently holds the record for the world’s most impressive bridges. At 48.3 kilometers (30 miles), the Hong Kong–Zhuhai–Macau Bridge is the longest bridge over water. Designed to withstand typhoons, it features cable-stayed bridges, an undersea tunnel, and is interrupted by four artificial islands—though the waters there are shallower than those of the Irish Sea.

The world’s longest bridge, the Danyang-Kunshan Grand Bridge in China, spans 164 kilometers (102 miles), while the Hangzhou Bay Bridge, at 36 kilometers (22.4 miles), crosses the largest stretch of open sea.

Tunnel vision

Grant Shapps, the UK’s transport minister, told the BBC in March that if a fixed sea link is built, the weather conditions make a tunnel more likely than a bridge.

The High Speed Rail Group, a rail industry association, has suggested a sea tunnel between Larne and Stranraer that could avoid Beaufort’s Dyke. However, the idea is based on plans from Victorian engineer James Barton, proposed 120 years ago. The group also recommends upgrading existing rail infrastructure in both countries to support the tunnel connection.

Another ambitious plan considered by UK government officials involves a three-tunnel system linked by an underwater roundabout beneath the Isle of Man, inspired by the new Eysturoy tunnel network in the Faroe Islands.

Engineer Ian Hunt has proposed a solution further south, utilizing the current ferry route infrastructure. He shared his design with New Civil Engineer for a bridge and tunnel link, featuring two artificial islands, connecting Holyhead in Dublin.

Political divide

The project is politically sensitive, with greater backing usually coming from Northern Irish and Scottish unionists, while nationalists tend to offer less support.

In Northern Ireland, the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), the largest political force, has been the most vocal advocate for the bridge, initially proposing the idea in its 2015 election manifesto.

The DUP, which struck a deal with the Conservative Party in 2017 that helped keep Johnson’s government in power, is now in turmoil, having seen three leaders in as many months.

Alan Dunlop shared with Dinogo that his Celtic Crossing proposal was met with largely positive feedback at first, but Scottish opposition grew after Boris Johnson publicly endorsed the bridge at the DUP conference in November 2018.

Nichola Mallon, Northern Ireland’s Infrastructure Minister and a member of the nationalist Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP), told Dinogo that the project was a 'vanity project from Westminster.' Mallon argued that a fixed link 'won’t deliver the expected improvements in jobs or trade until we’ve addressed the long-standing issues within our existing transport network.'

The £20 billion estimate is commonly cited in discussions about the project, but experts suggest the actual costs could be far higher.

Paul Quigley notes that the £20 billion figure is based on the technology used for the Channel Tunnel, completed in 1994. However, the Irish Sea project’s costs could exceed that estimate due to 'a very different era of environmental compliance and risk assessments.'

Then there’s the issue of the infrastructure upgrades needed to support the fixed sea link—costs that many on both islands argue would be better spent on other community investments.

'It’s hard to make an economic argument for it, but the project isn’t really about economics,' Dunlop tells Dinogo. 'It’s about the future of our countries and creating something meaningful for the next generation.'

It’s an ambitious vision for the future, but its success will require widespread support from the four nations that make up Britain and Ireland.

Much like the legend of the Giant’s Causeway, where the Irish giant Finn McCool built a bridge only to see it destroyed in a fight with the Scottish giant Benandonner, the project could ultimately be seen as an audacious tale of overreach—but the challenge is far from impossible.

Evaluation :

5/5