They left South Korea seeking the American Dream, but now their children are returning to their roots.

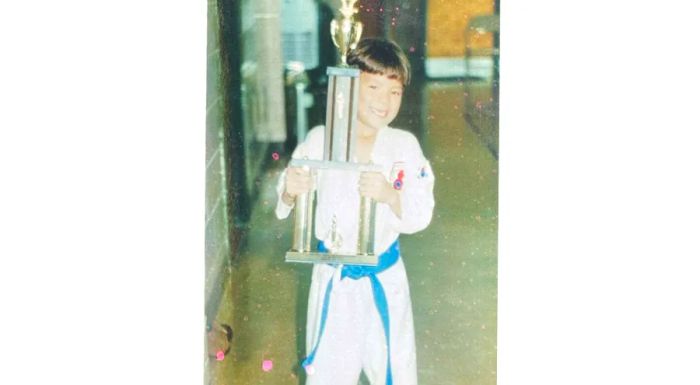

Growing up in North Carolina, Kevin Lambert always felt different from his White classmates. His Korean features, inherited from his mother, made him stand out, and he often felt like an outsider.

“Throughout my childhood in the '80s and '90s, the question I always got was: ‘Are you Chinese? Do you know kung fu?’” he recalled.

That sense of discomfort followed him into adulthood, eventually leading him to move to South Korea in 2009, searching for the elusive “missing piece” that would make him feel whole.

He represents one of many Asian Americans whose parents, having left postwar South Korea to chase the American Dream, now see their children reversing that journey back to Korea.

While it may seem unusual, especially when many have never stepped foot in South Korea, the pull of acceptance in one's ancestral homeland is powerful—especially when compared to the racism, gun violence, and anti-Asian hate crimes that have become rampant in the United States.

These return migrants were raised in an era when many Americans’ understanding of Asia was limited to Japan and China, often filtered through harmful stereotypes, according to Stephen Cho Suh, assistant professor of Asian American studies at San Diego State University.

The experience of being racially marginalized and not fully accepted as American has driven many to seek a connection to their parents’ homeland—a search they might not have considered had they felt entirely embraced by American society, Suh noted.

However, life in South Korea comes with its own set of challenges, leading many to eventually return to the United States. For some, even with deep ties to both cultures, relocating thousands of miles away doesn't bring them closer to finding a true sense of home.

‘Race is always a topic of conversation’

Several factors have fueled this reverse migration. In 1999, South Korea enacted a law that allowed “overseas Koreans,” including children of immigrants, to return more easily and stay for extended periods of time.

The 2002 FIFA World Cup, co-hosted by South Korea and Japan, along with the Great Recession of 2007-2009, which pushed many to teach English in South Korea as a means of escaping a struggling job market in the US, also contributed to this migration trend.

But according to Suh, who interviewed over 70 individuals as part of his research on reverse migration, one factor consistently emerges: “Race, racism, ethnicity,” he said.

After Daniel Oh immigrated from South Korea with his family as a child, he moved to Canada and then the United States, where casual racism became a daily part of his life. Now 32, Oh recalls countless moments when he felt ashamed of being an immigrant.

“I tried to distance myself from my foreign background as much as possible,” he said. But “no matter how fluent your English is, how many cultural references you pick up, or how much you blend in with behavior and speech… you’re always, at best, still seen as Asian American.”

When he started visiting Korea in his 20s, the country had changed so much from what he remembered. His Korean language skills were rusty, yet he still felt an undeniable sense of belonging. In Korea, the things that made him feel different in the US—his personality, mannerisms, and identity—suddenly made perfect sense.

With each visit, the pull to Korea grew stronger—until, at 24, he moved to Seoul, where he has lived for the past eight years.

Many migrants experience a 'honeymoon phase,' during which they revel in blending into a crowd of familiar Korean faces and feel a newfound sense of belonging, said Ji-Yeon O. Jo, director of the Carolina Asia Center at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Economic factors also play a role. Numerous Korean American musicians have risen to fame in South Korea's booming K-pop scene—such as Tiffany, Jessica, and Sunny from Girls’ Generation, and soloists like Eric Nam and Jessi. In contrast, there are few Korean American pop stars of similar renown in the United States, suggesting that 'the invisible bamboo ceiling' remains a significant barrier, Jo pointed out.

Older immigrants are often focused on retirement plans.

It’s not only the children of immigrants who are returning: many first-generation Korean Americans are also making the move back.

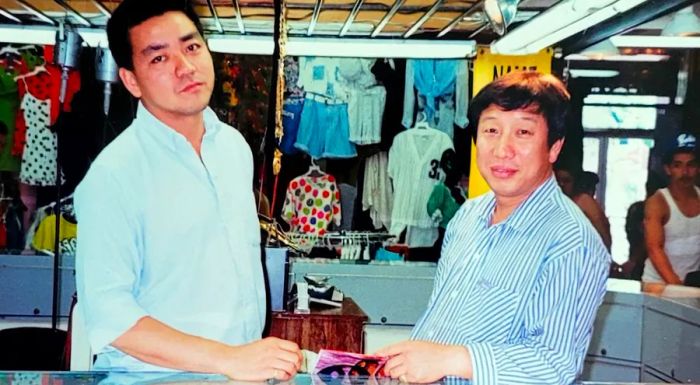

Kim Moon-kuk, 72, emigrated from Seoul to Los Angeles in 1985 with his wife and two children. Over the years, he ran several businesses, including a restaurant, a flea market, a gold and silver shop, and a sewing factory.

In 2020, he and his wife moved back to South Korea, settling in Chuncheon, a city in the northern part of the country. The move offered numerous advantages: affordable healthcare, the comfort of speaking Korean, and proximity to family.

Life in the US had been marked by persistent and overt racism. Kim remembers a time in the 1990s when he went to a bar where White patrons were waiting outside. He was turned away with the excuse that it was a “members only” establishment.

During much of the riots, law enforcement was absent from the burning Koreatown, forcing shop owners and residents like Kim to defend themselves.

Kim noted that life for Asians became increasingly difficult during the Trump era, especially with the former president repeatedly referring to Covid-19 as the “China virus” and “kung flu.” This rhetoric contributed to a rise in anti-Asian hate incidents.

For Kim, returning to South Korea has brought peace of mind, as the safety there is “100% better” than in the US.

“I plan to live here in South Korea until I die,” he said.

This sentiment is common among aging Korean Americans, according to assistant professor Suh, though not everyone can make the move. After decades abroad, many have lost contact with family and friends or feel too old to relocate. For those who do return, the country they left behind may feel unrecognizable. Despite rapid development, the cost of living in South Korea has also soared in recent years.

Encountering a ‘mirror image of racism’

The return many migrants envision rarely matches the reality. Once the initial excitement fades, they begin to experience tension between 'everyday life in Korea' and 'the values and lifestyles they've grown accustomed to in the US,' Jo explained.

Even simple tasks such as finding an apartment, opening a bank account, and registering with a doctor become more difficult due to language barriers and unfamiliar procedures.

“One of the toughest challenges of being a Korean American in Korea is dealing with a kind of double standard,” said Oh. “You’re seen as a foreigner in some ways... but expected to be more 'Korean,' even though non-Korean foreigners would be given more leeway.”

It often felt like an additional challenge to constantly prove that you were 'Korean enough,' he added.

It's a common experience: many share stories of receiving strange looks when speaking English on public transportation, Jo noted. Some are even approached by strangers asking, 'You’re Korean, why don’t you speak Korean?' or, when struggling with medical terms, they are confronted with, 'Aren’t you Korean?'

In some ways, these encounters reflect the challenges their parents faced when they first immigrated to the US.

“We’re witnessing a mirror image of racism—here, it’s intra-ethnic discrimination based on nationality, whereas in the US, it’s interracial racism,” Jo explained. “The dynamics may differ slightly, but the way they play out in daily life shows striking similarities.”

Experiences like these prompted Lambert to return to the US in 2020, after spending 11 years in South Korea.

“As a society, you’re not welcomed there,” he remarked. “The policies make it clear you’re unwelcome. The visa system says you’re not wanted. The way workers are treated shows that you’re not part of the community.”

Obstacles mount

Other factors contribute to some reverse migrants’ decision to return to the US. Maintaining connections with loved ones from home can be challenging. Dating is often difficult as well. Many women struggle with South Korea’s conservative gender and dating expectations, which label them 'too outspoken… not demure enough, too feminist,' said Suh. On the other hand, men may find it hard to form relationships without having 'employment in desirable jobs.'

Employment is one of the most significant hurdles. While teaching jobs are relatively easy to come by, transitioning into other industries is far more difficult. Whether due to their background or visa status, Korean Americans may face discrimination from employers in different sectors, according to Suh.

Worried about missing out on career opportunities in the US, Oh is now contemplating a return to America.

“My parents worked tirelessly to bring me to America,” he said, feeling a deep sense of responsibility to “make something out of the opportunities given to you.”

In addition, Oh shared that life in Seoul as a Korean American began to feel like a diminishing return.

“At first, spending more time in Korea felt like a direct path back to my Korean roots. But over time, I realized there’s only so much of Korea I can really reconnect with,” he explained.

As his friends and family moved forward with their lives in the US, “I didn’t feel like the same kind of opportunities were unfolding for me in Korea… You start to get less and less out of it as time goes on.”

Even first-generation Korean Americans can find it difficult to adapt to a country that is so different from the one they left behind. Lambert’s mother recalls Korea as a place of hardship; her father died in the Korean War, her mother succumbed to cancer without proper medical care, and she made a living by carrying rocks from under bridges destroyed in the war.

In stark contrast, the Korea she revisited many years later was filled with LED screens, modern infrastructure, clean streets, and the unmistakable signs of progress. With each return, Lambert said, “she felt more and more disconnected from Korea.”

Kim was also taken aback by the transformation. The rice fields he used to pass on his way to school had been replaced by a Samsung semiconductor plant. He sometimes struggles with the ever-present phone apps and automated store kiosks, and he misses the open spaces of rural Korea.

Unlike Oh and Lambert, he has no reservations about staying. In fact, had he known how developed the country would become, he might not have ever left.

“If South Korea were still as poor as when I left, why would I come back?” he said. “I returned because it’s as wealthy as the US now.”

Caught between two identities

For many younger Korean Americans, migration leads to a shift in how they understand their own identity.

Suh noted that some people become more aware of their American identity when they realize they don’t fit the South Korean idea of what it means to be Korean.

This sense of being in-between is especially prevalent among Korean Americans, who often want to balance their ties to both countries while maintaining their US citizenship, Jo explained. This is in contrast to reverse migrants from other nations who typically naturalize as South Koreans.

Many Korean Americans mention reasons like the desire to raise a family in the US, or the reluctance to have their children experience South Korea’s intense, competitive education system, Jo said.

The outcome is the creation of a personal space where they can embrace both identities, holding strong connections to both countries. It’s a balance of saying, “I’m Korean, but I’m also American,” Jo added.

Now, Oh finds himself torn between the two countries, unsure of his future and unable to fully let go of either place.

“The reality is that, no matter what, it’s difficult to feel complete,” he said. “There’s always a pull towards the other world because once you’ve experienced both, you come to understand the pros and cons of each life you’ve lived.”

1

2

3

4

5

Evaluation :

5/5