Travel writers like James Baldwin and V. S. Naipaul have long shared diverse viewpoints, enriching our understanding of the world.

In 1925, Aldous Huxley embarked on a global journey to gather inspiration for his travelogue, Jesting Pilate. At just 31, he was already a celebrated literary figure in London and was warmly welcomed in India. During a tea gathering in Bombay, he witnessed a young Muslim recite verses by the Urdu poet Muhammad Iqbal, lamenting Sicily's loss to infidels, which struck Huxley profoundly.

Upon hearing the translation, Huxley felt a personal indignation. He argued that for Europeans, Sicily is defined by its Greek, Latin, and Christian heritage, and the Arab influence merely an irrelevant chapter in its history.

However, as Huxley reflected, he realized that the clash of perspectives—where different narratives compete over the same space—defines the essence of travel. He noted that in a traveler's journey, such insights into relativity are commonplace occurrences.

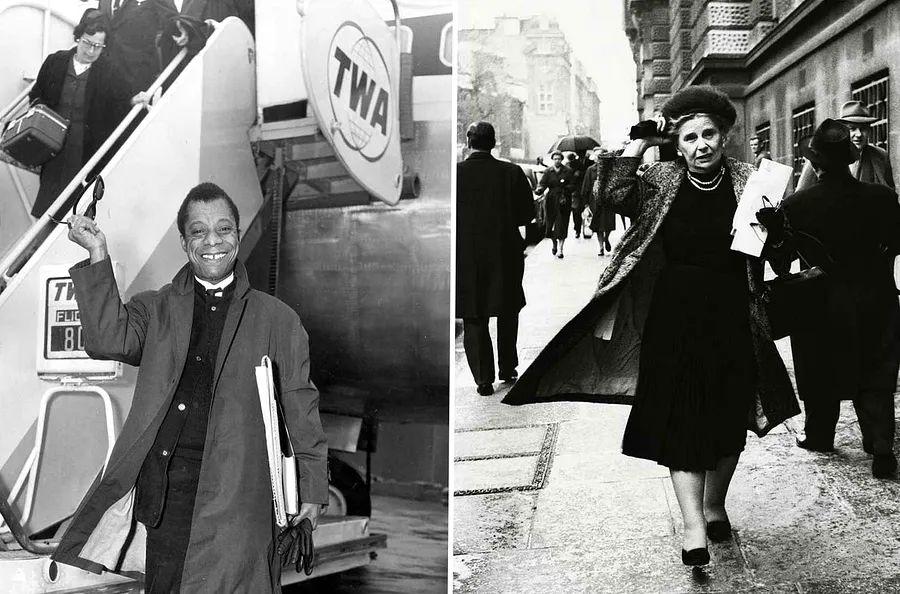

V.S. Naipaul, the Trinidadian writer, captured in Paris during 1992. A. Abbas/Magnum Photos

V.S. Naipaul, the Trinidadian writer, captured in Paris during 1992. A. Abbas/Magnum PhotosThe indignation Huxley experienced in Mumbai, as travel confronted him with an alternative historical narrative, resonates strongly in today’s context. Around the globe, from Seattle to Brussels and Cape Town to Bristol, statues are being removed and institutions renamed, targeting figures tied to racism and slavery (like King Leopold II and Woodrow Wilson) as well as those once seen as heroes (such as Gandhi and Winston Churchill). History, with a capital H, is more dynamic than ever.

Globally, our established views of the past are facing disruption, prompting a reevaluation of everything from the authors we read to the composition of our newsrooms. Which voices have been elevated, and which silenced? Do the figures we celebrate reflect our own identities? Are certain races, genders, or backgrounds overrepresented while others are marginalized? Huxley traveled to India to confront his own values; now, as the West reassesses its history, this discomfort is returning home.

While many in the U.S. may be encountering this sensation for the first time, it is familiar to a group of travel writers I find particularly engaging—those I refer to as "outsiders." These authors, shaped by their race, gender, sexual orientation, or class, cannot traverse the world as if it belongs to them, granting them a unique clarity as they engage with the cultures they encounter.

One of my favorite writers from this group was the late V.S. Naipaul, who served as a sort of mentor to me. Descended from Indians sent to the Caribbean as indentured laborers post-slavery, Naipaul stood in contrast to Huxley, who hailed from what he called "that impecunious but dignified section of the upper middle class" and represented an empire that governed a significant portion of the globe, while Naipaul embodied the true outsider experience.

In his 1990 work, India: A Million Mutinies Now, Naipaul captures a process of awakening that resonates with our current moment. He wrote, "To awaken to history" means moving beyond instinctive living, seeing oneself and one’s community through the lens of the outside world, and experiencing a certain kind of rage.

I have always been acutely aware of the outsider's role in travel writing. Growing up gay and of mixed heritage (half Indian, half Pakistani) in New Delhi, I later lived in the UK and eventually settled in the United States. My spouse hails from Tennessee and comes from an evangelical Christian background. For someone like me, adopting a singular viewpoint was never feasible.

When I began my writing journey, I noticed that the travel literature available to me was predominantly authored by Europeans. This left the voices connected to my race, religion, culture, and language largely unheard, or only partially expressed. For instance, my grandfather, a poet from Lahore and a student of Muhammad Iqbal—the poet Huxley encountered in Mumbai—could easily have represented the "young Mohammedan" in Huxley's narrative. Yet, I must conjure him into being, as he remains a silent caricature in Huxley’s essay.

The Hungarian author Arthur Koestler captured aboard a zeppelin headed for the North Pole in 1931.

nullstein bild via Getty Images

The Hungarian author Arthur Koestler captured aboard a zeppelin headed for the North Pole in 1931.

nullstein bild via Getty ImagesThe desire to give voice to those silenced by history has birthed a new literary genre. In 2013, Kamel Daoud, an Algerian journalist, published The Meursault Investigation, which reinterprets Albert Camus' The Stranger through the eyes of the Algerian whose brother is slain by Meursault, the protagonist of Camus’ novel. Daoud’s work addresses the historical void, challenging the enforced silence of the past and striving to share the untold side of the narrative.

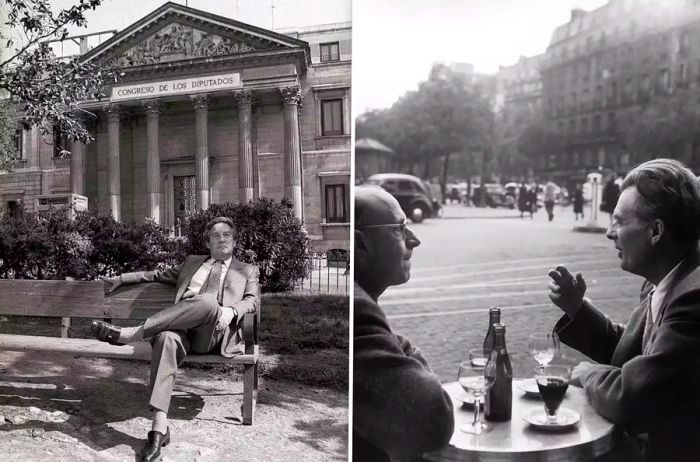

Lacking a single culture or literary tradition to rely on, it's crucial to seek out voices that fulfill the need for representation. In my own journey, I have been drawn to figures like Arthur Koestler, a Hungarian Jew who was displaced from multiple European countries in the early 20th century before settling in England. I also found resonance in Octavio Paz, a Mexican Nobel laureate and diplomat who wrote about his experiences in Paris, Tokyo, and New Delhi in his book, In Light of India.

Paz and Koestler shared no direct similarities, aside from both being quintessential outsiders. Neither could claim to speak from a position of power or cultural authority. Their unique perspectives, approaching their subjects from an oblique angle, connect them as kindred spirits.

Upon moving to the United States, I found myself frustrated with the country's relationship to history, as if it was somehow exempt from the past's demands. It was Paz, writing from afar, who resonated with my unease. He observed that in places like India, "the future to be realized implies a critique of the past." In contrast, Paz suggested that for the U.S., "the past of each ethnic group is a private matter; the nation itself has no past. It was born with modernity; it is modernity."

The United States undoubtedly has a past now, one that refuses to be silenced. We must confront whether the American desire to escape history stems from a wish to avoid painful or difficult narratives. Once more, it is an outsider—a British woman—who offers insight. In the late 1940s, Rebecca West, the author of Black Lamb and Grey Falcon, a profound exploration of history’s lingering effects in the Balkans, reported from Nuremberg during the Nazi trials.

In her writings, she recounted an earlier incident in the U.S. involving an American newspaper owner with significant industrial interests who was showing European guests around his establishment, and a Black elevator operator who, it turned out, was illiterate and hailing from the South. Sensing the tension, one of the Europeans noted, "Ah, yes, you Americans have your problems like the rest of us," suggesting that America too is bound by historical realities. West described the newspaper owner as displaying brutal contempt when he replied, "No, we have not. You have all the problems over in Europe. Here in America, we have nothing to do but get rich. We shall be a country with no history."

All writers, inherently shaped by their era, are not exempt from prejudice. However, these biases seem trivial compared to those reinforced by the power of empires or dominant nations. It is the outsider who challenges these ingrained notions, highlighting their crucial role. The prevailing beliefs in any society are seldom innocent. The strongest claims often silence those whose experiences differ significantly from ours. The outsider's presence is vital as it disrupts our self-perception, serving as a deliberate provocation.

On the left, Mexican diplomat and author Octavio Paz stands before the Spanish parliament in Madrid in 1982; on the right, Aldous Huxley chats with a friend on the terrace of Café de Flore in Paris during the 1940s.

Image credits: Quim Llenas/Cover/Getty Images; Robert Doisneau/Gamma-Rapho/Getty Images.

On the left, Mexican diplomat and author Octavio Paz stands before the Spanish parliament in Madrid in 1982; on the right, Aldous Huxley chats with a friend on the terrace of Café de Flore in Paris during the 1940s.

Image credits: Quim Llenas/Cover/Getty Images; Robert Doisneau/Gamma-Rapho/Getty Images.A prime example is found in "Stranger in the Village," the concluding essay of James Baldwin's brilliant collection, Notes of a Native Son, published in 1955. In this essay, Baldwin reflects on his arrival in a small Swiss village, where, reportedly, the locals had never encountered a Black man before. What ensues is perhaps the most profound illustration of the outsider's gaze in travel literature. Baldwin utilized the village's isolation as a stage to reenact the complex meeting of Black and white cultures in North America, encapsulating the wonder, fear, and trauma inherent in that interaction.

In contrast to the newspaperman in West's narrative, Baldwin recognized the weight of history in America: "People are trapped in history and history is trapped in them." This is not the sanitized version found in textbooks; it is the raw, unresolved history simmering beneath the surface of society, marked by pain, conflict, and the deep unease of perceiving oneself through the eyes of others.

Baldwin once remarked to his white peers, "You never had to look at me. I had to look at you. I know more about you than you know about me."

To grasp what the outsider understands about us—how we present ourselves to those who differ from us—we seek the most insightful moments in travel writing. We do this because, as Baldwin poignantly stated, "Not everything that is faced can be changed; but nothing can be changed until it is faced."

This story was originally published in the October 2020 issue of Dinogo with the headline The Writer and the World.

1

2

3

4

5

Evaluation :

5/5