Why Kenya is focused on counting each and every animal

With his notepad in hand, the wildlife researcher carefully ticks off each elephant as it enters his sight, determined not to miss a single one in the herd.

Meanwhile, the pilot circles high above Kenya's Amboseli National Park in a helicopter, offering a clearer view of the herd – and, notably, an incredibly rare sight: twin baby elephants.

‘The last time Kenya saw twin elephants was 40 years ago,’ says Najib Balala, Kenya’s tourism minister, his voice crackling through the headphones.

During the pandemic, Kenya has witnessed an unexpected surge in baby elephants, with over 200 new calves – or what Balala calls the ‘Covid gifts’.

While some animals have thrived in the quieter parks during the pandemic, Covid-19 has wreaked havoc on wildlife conservation across Africa, along with the livelihoods of millions reliant on ecotourism.

In March 2020, Kenya closed its borders to slow the virus spread, bringing the country’s multi-billion-dollar tourism sector to a standstill, losing over 80% of its revenue. Recovery isn’t expected until 2024, according to Balala.

‘Can tourism survive until 2024? We need to rethink and reshape our approach to ensure survival until tourism rebounds,’ Balala tells Dinogo.

This ambitious goal has sparked Kenya’s most extensive conservation initiative yet: a nationwide effort to count every animal and marine species across all 58 national parks, a first in the country's history.

The grand wildlife census is crucial for understanding and safeguarding the more than 1,000 species native to Kenya, many of which have faced alarming population declines in recent decades, according to experts.

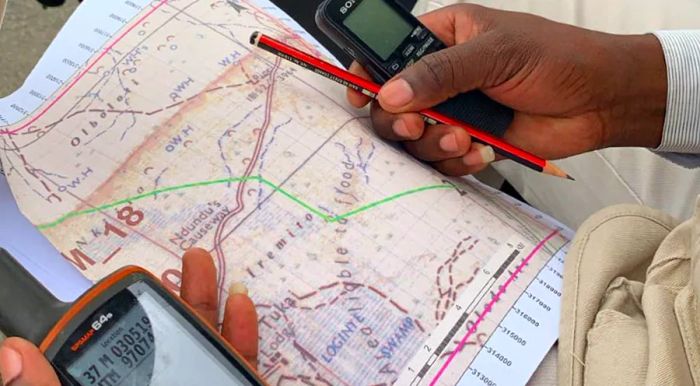

Kenya's Wildlife Service (KWS) is deploying GPS trackers, aircraft, camera traps, and extensive manpower to catalog everything from the majestic giraffe to the tiny dik-dik over the course of three months.

The focus will be on endangered species like the pangolin – often a target of illegal trade – the sitatunga antelope, aardvarks, and hedgehogs, none of which have been counted before.

Shrinking habitats

This unparalleled data will provide Kenya with deeper insights into its wildlife and the mounting threats it faces today, such as climate change, human-wildlife conflict, and diminishing habitats due to increasing land competition.

For years, the Maasai have sacrificed their land to make way for some of Kenya’s most iconic parks. Noah Lemaiyan, a herdsman in his red and blue shawl, lives on the edge of Amboseli. He says that since the tourists stopped coming, his village’s income has vanished.

‘Women used to craft bracelets and necklaces,’ he explains. ‘Now we must sell a cow just to buy food.’

Lemaiyan is also facing a severe water shortage, essential for keeping his herd alive.

Dr. Patrick Omondi, acting director of biodiversity, research, and planning at KWS, hopes that the census will provide clearer insights into how unpredictable weather patterns are impacting wildlife and forcing them to adapt by moving to new habitats.

‘We will pinpoint where these animals are located in both time and space,’ he explains – a strategy that will help them develop a more effective management plan.

‘We have observed wildlife venturing into areas they haven't inhabited in 50 years,’ he adds.

By the end of July, Omondi and his team of hundreds will have thoroughly explored every inch of Kenya’s vast landscapes, both from the air and on the ground, while also surveying all lakes and marine parks by boat and underwater.

Once the census is finished, the real work will begin.

1

2

3

4

5

Evaluation :

5/5