A Mexico City Mayor Attempted to Erase Street Food Art, But the Community Is Resisting.

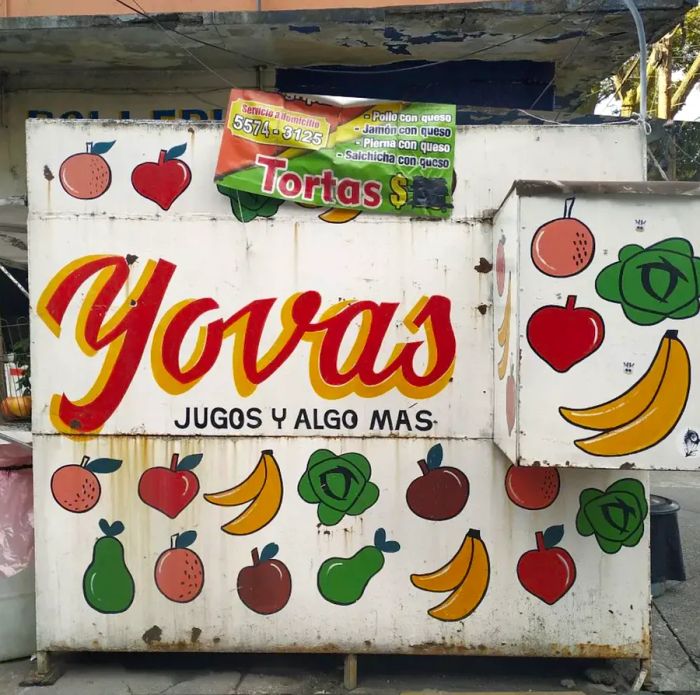

Since 2004, Tamara De Anda, a dedicated Mexican activist and television personality, has captured the essence of street art in Mexico City, showcasing vibrant images on social media that highlight the playful, irreverent, and charming pieces that adorn the city. Many of her focuses are on rótulos, the hand-painted signs that feature lively typography and clever illustrations to promote various businesses, concerts, sporting events, and, notably, street food vendors. Rótulos have been a staple of the urban landscape since the early 20th century. Despite a decline due to the rise of vinyl and digital ads over the past two decades, they have flourished in Cuauhtémoc, a lively district of CDMX that includes popular neighborhoods like Centro Histórico, Roma, and Condesa, where vendors proudly display rótulos showcasing joyous tacos, tortas, jugos, caldo de gallina, birria, guisado, and tamales.

Then, towards the end of April, the whimsical rótulos vanished. Residents awoke to find the vibrant signs had been painted over in white. In their place was the logo of the Cuauhtémoc district.

Rótulos Chidos / Instagram

Rótulos Chidos / Instagram Rechida

Rechida Rechida

Rechida Rechida

RechidaFood stands featuring rótulos prior to the government initiative, and district signage afterward.

Their removal was part of the district’s Comprehensive Campaign for Urban Improvement, aimed at enhancing the neighborhood's appearance. Launched last April by Mayor Sandra Cuevas, this program sets operational standards for street vendors, which include keeping work areas tidy, staying within assigned zones, minimizing waste, cultivating a small urban green space, and, importantly, displaying the official Cuauhtémoc logo. The official press release states, “The cleanliness and beauty of the district is everyone's responsibility.” If aesthetic pressure wasn’t enough, it also warned that noncompliance could lead to revoked street selling permits.

Since the campaign began, over 1,500 street food stalls have lost their unique graphic identities. Numerous vendors—who requested anonymity due to fears of retaliation or permit loss—report that Cuevas's administration charged them between 200 to 300 pesos ($10 to $15) for the unwanted paint and the new logo. Others were pressured into buying a white tent featuring the logo to cover their stalls, at a similar cost.

For De Anda, residents, street vendors, and rótulistas (sign painters) like Isaías Salgado, this action is seen as an assault on an essential yet fragile art form within Chilango culture. Salgado, originally from Tepito (a neighborhood in Cuauhtémoc), has spent 35 years painting rótulos, alongside his work for brands, galleries, and exhibitions. “I used to know over 200 sign painters; now I can count only four or five who are still in the trade,” he reflects. “Regardless of what Sandra Cuevas claims, I believe sign painting is an art form and a crucial part of our identity as Mexicans and Chilangos.”

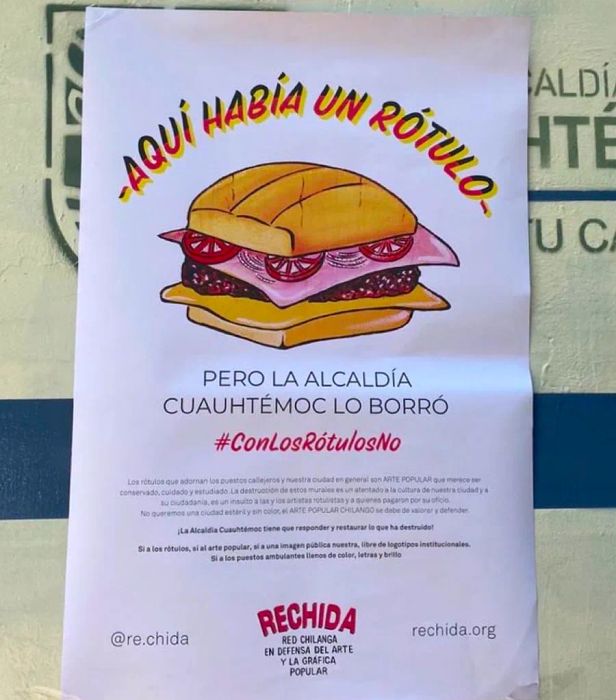

Suddenly, De Anda’s mission to preserve street art has gained renewed significance. By the second week of May, she teamed up with fellow artists, graphic designers, and activists to establish Rechida (Chilanga Network in Defense of Art and Popular Graphics), a collective dedicated to safeguarding artworks throughout Mexico City. The erasure of rótulos is merely the latest in a series of assaults on street vendors, who have historically faced discrimination, marginalization, and economic exploitation through bribes and corrupt government practices. “We need to recognize street food as a cultural and culinary system that thrives in public spaces, yet there is no regulatory framework or city code that protects street vendors' rights,” De Anda asserts.

A day without rótulos.

Rótulos Chidos / Instagram

A day without rótulos.

Rótulos Chidos / InstagramRechida launched a campaign to persuade residents and government officials of the significance of rótulos as a key element of Mexico City’s cultural identity. Over the summer, the group organized hearings with the cultural department to advocate for the protection of these signs and is petitioning Seduvi, the urban development and housing department, to preserve public spaces traditionally painted by rótulistas. In collaboration with other social media initiatives like PinturaFresca.mx and rótulos.chidos, they are also urging locals to help document lost signs through a geotagged digital archive. Beyond safeguarding the artworks, Rechida is working on legislation to protect vendors, ensuring their right to advertise and access permits, and compensating those adversely affected by Cuevas’s initiative.

The discussion surrounding rótulos has ignited deeper social and economic issues within the community, intensifying tensions related to gentrification and class in Mexico City. During a public hearing on May 21, media and community representatives challenged Cuevas about the development campaign. She stated that the program aimed to unify the urban landscape, enforce order, and beautify the district. 'Thus, we removed the rótulos, which are not seen as art,' she remarked. 'While they may be part of Mexico City's customs and traditions, they do not qualify as art.'

“There remains a prevailing perception among [mostly affluent] Chilangos that street vendors evade taxes and that street stalls detract from public aesthetics,” De Anda notes. Cuevas, elected last year as the face of the right-wing coalition Va por México, has made her stance clear regarding food stalls and popular graphic culture on the streets: Rótulos are not deemed 'beautiful.'

Rechida flyer

Hugo Mendoza

Rechida flyer

Hugo MendozaHowever, many low-income and working-class residents stand in solidarity with taqueros and street food vendors. For some, selling food from markets, stalls, bicycles, or carts is often the only way to secure a stable income. For millions, street food provides an affordable means to feed their families. Street food vendors typically lack access to formal investment or credit from banks or government programs; rótulos serve as an accessible method of self-promotion and survival. “Every business, regardless of size, has the right to showcase its name and brand in the way they see fit. Why does the government think they can dictate the colors and logos of street stalls? Why don’t they regulate the logos and colors of major brands like Starbucks and Oxxo?” De Anda questions.

While the struggle over rótulos unfolds throughout the city, it’s most pronounced in Cuauhtémoc, a neighborhood experiencing rapid gentrification, earning it the nickname “the white bubble” among Chilangos. Especially since the COVID-19 pandemic, residents have become increasingly aware of rising rents and living costs. Many are also apprehensive about the influx of wealthy digital nomads from the United States, Canada, and Europe. Although these newcomers are attracted to Cuauhtémoc’s vibrant street culture, De Anda argues that the government is attempting to sanitize the city to draw in more immigration, real estate investments, and visibility for her political coalition, which shares the blue and white colors of the Cuauhtémoc logo.

As the neighborhood evolves, rótulista Giovanni Bautista worries that the loss of rótulos signifies a loss of the city's collective memory. Bautista has been working on rótulos since his teenage years, having learned the craft from his father, Arturo Bautista, who opened his workshop in 1983 in Villa de Etla, Oaxaca. “The rótulo conveys identity to a business. It’s part of the evolution and history of each street food stall. Such graphic expressions shape the identity of neighborhoods and contribute to the narrative of each street in our cities and our relationship with public space,” Bautista reflects. “I genuinely believe that the Cuauhtémoc district authorities have erased a part of Mexico City’s history.”

As rótulos face challenges locally, the culture has found ways to thrive globally. Bautista has crafted rótulos for taquerias and food businesses overseas, with his hand-painted works reaching Germany, Argentina, the United States, and Peru. In May, Salgado teamed up with contemporary Mexican artist Pedro Reyes on the Zero Nukes installation in New York, where he hand-lettered an inflatable mushroom cloud that was displayed in Times Square.

Fabiola Pérez Solís via Rótulos Chidos / Instagram

Fabiola Pérez Solís via Rótulos Chidos / InstagramIn Mexico City, Chilangos have traditionally thrived amidst the vibrant chaos of street culture, including rótulos. However, they have also endured local and city governments that show little regard for preserving the unique cultural expressions that define the city.

“It’s so dull and disheartening that everything has turned plain white. True beauty lies in diversity, color, playfulness, and uniqueness,” De Anda remarks. “Once street food stalls are allowed to display their rótulos again, we’ll advocate for commissions to traditional sign painters to gradually restore the color to the streets of Mexico City.” Until then, it falls to vendors, artists, and the community to safeguard rótulos and the memories they embody. She concludes, “Street food always finds ways to adapt and thrive.”

Natalia de la Rosa is a Mexican food writer, mezcal collector, and culinary guide based in Mexico City.

1

2

3

4

5

Evaluation :

5/5