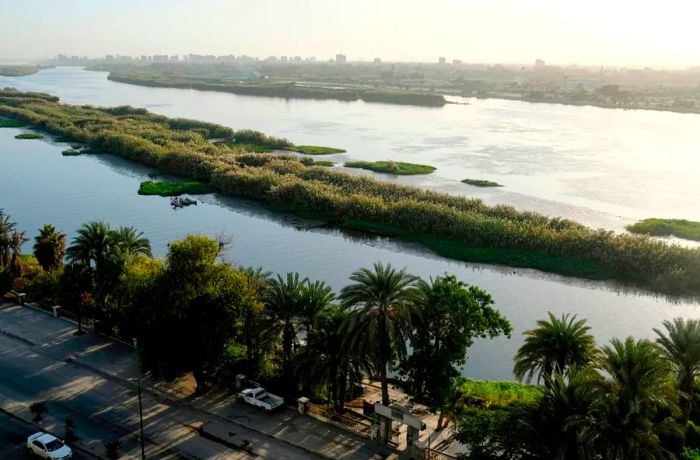

A now-dry branch of the Nile played a crucial role in the construction of Egypt’s pyramids, according to a new study.

New evidence regarding the Nile strengthens a long-held theory about how the ancient Egyptians constructed the monumental pyramids of Giza thousands of years ago.

Led by geographer Hader Sheisha from Aix-Marseille University in France, researchers used paleoecological data to reconstruct the ancient flow of Egypt's Nile river over the past 8,000 years.

The team concluded that the pyramid builders likely exploited an extinct branch of the Nile to transport building materials, according to a study published on August 24 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Their findings suggest that around 4,500 years ago, the former river landscapes and elevated water levels provided the necessary conditions for constructing the Giza Pyramid Complex, the study concluded.

The Great Pyramid rises to a height of about 455 feet and was commissioned by Pharaoh Khufu during the 26th century BC. Made up of 2.3 million stone blocks weighing a total of 5.75 million tons (16 times the weight of the Empire State Building), it remains the largest pyramid at Giza. The other major pyramids are dedicated to Khufu’s son Khafre and his grandson Menkaure.

Situated on the Giza plateau near Cairo, these monumental structures are surrounded by temples, tombs, and the quarters of workers, making them the oldest of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.

Ancient engineers likely relied on floods as hydraulic lifts to move materials.

For years, scientists have speculated that ancient Egyptians used parts of the Nile river to transport the enormous quantities of limestone and granite needed to build the pyramids. Modern-day Nile channels are too distant from the pyramid sites to have been used.

The 'fluvial-port-complex' hypothesis suggests that Egyptian engineers dug a small canal linking the pyramid site to the Nile’s Khufu branch. The annual floods filled dredged basins, functioning like a hydraulic lift, and enabled the movement of massive stone blocks to the construction site, the researchers concluded.

However, until now, researchers have lacked a clear understanding of the specific landscapes involved in this process.

By combining various techniques to reconstruct the ancient floodplain of the Nile, the research team suggests that Egyptian engineers may have used the now-dry Khufu branch of the Nile to transport materials to the Giza pyramid construction site.

The team first studied rock core samples taken in 2019 from the Giza floodplain to estimate the water levels in the Khufu branch thousands of years ago. They also analyzed fossilized pollen found in clay deposits around the Khufu region to identify areas that were rich in vegetation, indicating higher water levels at the time.

Their findings indicated that the Khufu area thrived during the early part of Egypt’s Old Kingdom, roughly from 2700 to 2200 BC, aligning with the period when the three main pyramids were likely built.

The Khufu branch maintained high water levels throughout the reigns of Pharaohs Khufu, Khafre, and Menkaure.

According to the study, 'From the third to the fifth dynasties, the Khufu branch provided a suitable environment for the development of the pyramid construction site, aiding in the transportation of stone and materials by boat.'

By the Late Period of Egypt, around 525-332 BC, the Khufu branch experienced a drop in water levels, a finding supported by studies of oxygen in mummies' teeth and bones from that era, which suggest lower water consumption.

By the time Alexander the Great took control of Egypt in 332 BC, the Khufu branch had been reduced to a mere small channel.

The data indicates that ancient engineers utilized the Nile and its seasonal floods 'to exploit the plateau area overlooking the floodplain for monumental construction.' Essentially, the Khufu branch of the Nile was sufficiently high to transport massive stone blocks, enabling the creation of the iconic pyramids we admire today.

Paleoclimatology plays a crucial role in shaping our understanding of both past events and future scenarios.

Joseph Manning, a classicist historian at Yale University, described this 'revolutionary' study as a prime example of how paleoclimatology is 'fundamentally transforming our grasp of human history.'

'We’re gaining a more nuanced and dynamic view of ancient human societies,' Manning shared with Dinogo.

Manning noted that these innovative methods, such as the pollen analysis used in this research, allow scientists to gain deeper insights into ancient societies that lived thousands of years ago.

'Climate science, as shown in this study, is providing us with entirely new insights... (which are) highly relevant to current events.' By studying climate changes during Egypt's Old Kingdom, scientists can better understand the trends we are facing today.

Historically, researchers focused mostly on texts to understand ancient Egypt, but as Manning pointed out, environmental science is now 'shaking things up' and revealing new perspectives on the ancient world.

The breakthrough in this study is the identification of a natural waterway that could have been used to transport pyramid-building materials, countering previous assumptions that a man-made canal was necessary, according to Manning.

For environmental history to reach its full potential, Manning stressed the need for collaboration between scientists and historians. 'It’s a different way of working, and there’s resistance to it,' he explained.

Despite the challenges, he added, the opportunities are 'incredibly exciting.'

1

2

3

4

5

Evaluation :

5/5