An overview of the evolution of American cuisine

Even if your Thanksgiving feast was more modest this year, if it still included dishes like squash, corn pudding, turkey, and cranberry sauce, you can thank Native Americans for those ingredients. But don’t forget the apple pie – while apples come from Kazakhstan, the pie itself is a British creation.

Defining what constitutes 'American food' can be a challenge, but many scholars, including Yale historian Paul Freedman, have attempted to do so. His book, “American Cuisine and How It Got That Way,”, published last year, dives into the subject.

According to Freedman, 'The joy of American dining is what sets it apart.' He adds, 'Even if many of our food choices, let’s be honest, aren’t the healthiest.'

Americans have a unique passion for food, and so do people around the world. Historians like Freedman point out that despite global influences, Americans share certain culinary characteristics that are distinctly their own. And it’s not all about deep-fried everything. Fast food remains an icon of American culture, even though we’re consuming it less these days. Still, we’re more than just McDonald’s and processed cheese – we’ve even influenced other food cultures, including France, who has picked up a few American dining habits of their own.

To better understand what unites our collective taste preferences, let’s explore five pivotal moments in the evolution of American food culture.

1) The era when sugar was considered a health food

Until the late 1800s, people mainly ate foods that were filling rather than nutritious. Dairy, meats, hominy, oatmeal, and sugar were diet staples, while vegetables were largely ignored. The importance of vitamins wouldn't be recognized until the 20th century.

'They avoided spices, believing they caused indigestion and distracted from the true flavor of the food,' explains Freedman, who points out that spices were often associated with lower-class cooking.

Historian Sarah Lohman clarifies that the food culture wasn't as bland as it may seem. Mary Randolph's 1824 cookbook, “The Virginia House-Wife,” includes chili peppers among its ingredients.

'American cuisine is deeply shaped by indigenous cultures, especially the contributions of enslaved people from the Caribbean and Africa,' says Lohman.

2) The journey of food across the country

In the 19th century, while New Englanders enjoyed brown breads and stuffing, the South was savoring dishes like pork, molasses, greens, and cornbread, often griddled or made from cornmeal.

Black chefs have played a crucial role in shaping American cuisine from the very beginning. Their influence spread from the South to the North, yet their contributions have often been overlooked over time.

A prime example is the tale of ice cream. James Hemmings, Thomas Jefferson's enslaved chef, accompanied the family to France, mastered the art of making ice cream, and returned to the U.S. with new knowledge, including copper cookware, French fries, and European-style mac 'n' cheese.

Historian Jessica Harris is the lead curator of the exhibition “African/American: Making the Nation’s Table” at the Museum of Food and Drink in New York City. She explains how Black chefs, in the early days, traveled with aristocrats heading to their summer estates in places like Newport. Later, Black Pullman car workers spread across the West with the railroads, bringing their familiar cuisine along. Following the Civil War, the Great Migration took Black culinary traditions to every corner of the country.

“It's about examining history and culture through the lens of food, which acts as a universal language,” said Harris. “Food is a wonderful lens because it’s something everyone can relate to.”

By the late 19th century, New England’s hearty but perhaps somewhat uniform cuisine began to take center stage.

3) The simple pleasure of home economics class

While scientific thinking about food has always existed, in the late 1800s, people began focusing on the unseen aspects of food, such as preventing diseases like scurvy, beriberi, and pellagra. Vegetables gained a bit more significance – though they were often cooked for hours on end.

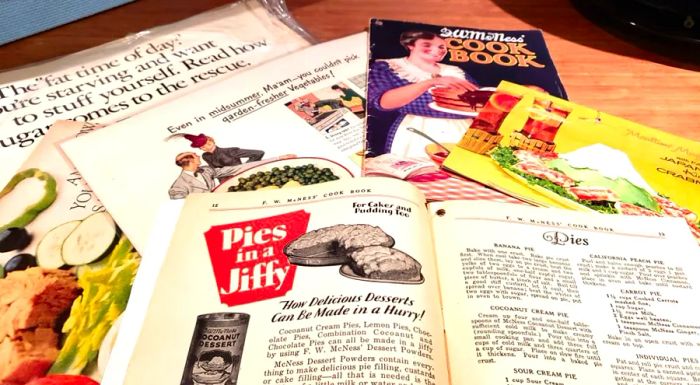

A woman’s kitchen became her laboratory, with cookbooks serving as her textbooks. What was considered “nutrition” became critical, yet many women were reluctant to learn cooking from their mothers, and certainly didn’t want to follow their methods.

'The idea was that you shouldn’t just do everything the way your mother did because, first of all, it was a tedious chore,' says historian Laura Shapiro, who specializes in women and food. 'It was hard, outdated work that wasn’t seen as modern.'

Starting in 1890, Fannie Farmer began transforming traditional New England dishes into more refined meals, though this sometimes meant the food was monochromatic in color, either all white or all brown. Her textbook eventually became “The Fannie Farmer Cookbook,” which remained a staple until it was surpassed by “The Joy of Cooking” in the 1930s.

Shapiro notes that while Farmer’s writing style was quite dry, she did have a playful side. She created the ginger ale salad, a dish that combines canned fruit, gelatin, and soda into a wobbly dessert.

Her cookbook was published just as families were beginning to move further from their original hometowns, spreading out across the country.

'You’re this young bride, newly married, and suddenly tasked with cooking in a new home without knowing how,' says Shapiro. 'Once you figure it out, you’ll be able to cook all these wonderful meals, and your husband will be healthy and avoid becoming an alcoholic.'

That’s a lot of pressure to place on your meatloaf. Fortunately, Americans received some help when we weren’t exactly prepared for it.

4) When we get help we don’t necessarily deserve

Immigration, migration, and the rise of mass production were key factors in the development of distinct American eating habits that set us apart from the rest of the world. While immigration is a global phenomenon, in America it occurred on an unprecedented scale and very early in our history.

Historian Sarah Lohman spent years leading tours and teaching classes about the immigrant experience at New York City’s Tenement Museum. She also traveled to 12 different regions across the U.S. to research her book, “Eight Flavors: The Untold Story of American Cuisine.”

'As domestic science began to shape American food culture, we also saw a significant wave of immigrants from Italy and Eastern Europe, particularly Jewish immigrants,' explains Lohman.

Lohman notes that Eastern Europeans brought their love for sour flavors, while Italians introduced garlic to American kitchens. Their food evolved in the U.S., with Italians, for example, embracing ingredients like olive oil and aged cheeses. In Italy, these were costly imports, but in America, they were affordable and used generously.

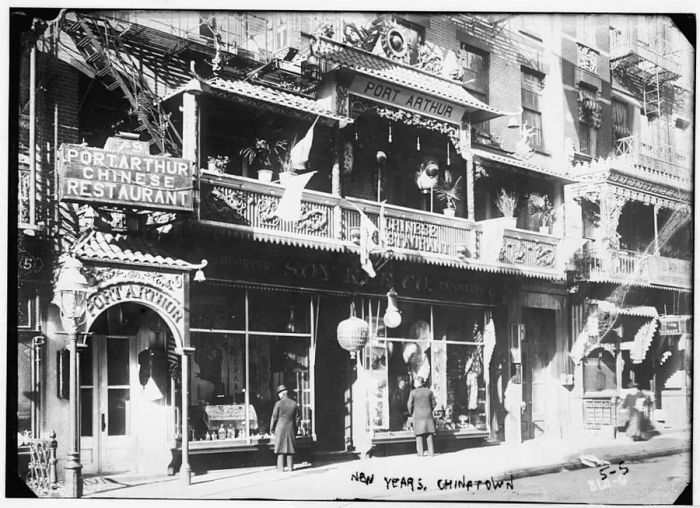

The spread of Chinese cuisine mirrors the growth of prejudice against Chinese people across the country. Kevin Kim, who researches the history of Chinese communities in the Deep South, is currently working on a project exploring the ongoing displacement of urban immigrant populations for the Smithsonian Anacostia Community Museum.

'One of the contradictions of this time,' says Kim, 'is that early Chinese food is simultaneously defined by exclusion and racism, yet there’s a simultaneous appetite for something foreign, yet familiar.'

The Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 sought to prevent Chinese laborers from entering the U.S. in search of work, though it allowed for certain exceptions. Merchants, including store and grocery owners, were exempt, and eventually, restaurant owners were too. As a result, the number of Chinese restaurants in the U.S. doubled between the early 19th century and the mid-20th century.

Kim explains that Chinese restaurant owners brought their traditional flavors and cooking techniques but modified them by incorporating local ingredients. For instance, broccoli, which wasn't used in China, became a common item on Chinese menus here. Additionally, Chinese chefs in African American and Caribbean neighborhoods began adding local dishes like collard greens and fried chicken to their offerings.

Another surge in Chinese food popularity occurred in 1965, when changes to immigration laws brought waves of people from across Asia. As immigration slowly began to influence American cuisine, the speed of American industrialization also ushered in a new era of culinary diversity.

5) Industrialization brings new flavors and an explosion of variety

Processed foods like cake mixes and powdered eggs were available before the World Wars, but their popularity surged after the wars ended. Innovations such as canned and frozen foods, originally developed to feed soldiers in large numbers, continued to be produced rapidly, and manufacturers began seeking new markets for these products.

To reach this new market, companies turned their focus to women at home. Grocery stores were key targets, as fresh produce required significant labor, and much of it went to waste—unlike the long-lasting canned goods like tomatoes that lined the shelves.

'The food industry wants you to think cooking is a major hassle and a burden on your time,' says Freedman. 'Otherwise, you’d just buy regular potatoes and mash them yourself, but they don’t make much profit from that. Instant mashed potatoes, on the other hand, are a different story.'

Shapiro argues that manufacturers built the idea that women were constantly busy and short on time. They created a world where every meal and every day felt like an emergency, forcing women to keep up with the pace of life.

'Never let anyone tell you women embraced it,' says Shapiro, criticizing the cheerful women portrayed in ads for convenience foods. 'That’s pure nonsense. Women resisted it fiercely, and the food industry was shocked by that.'

As decades passed and schedules became more packed, processed foods remained in the picture. However, instead of a simple can of tomatoes, consumers now face a choice of Italian-style, Spanish-style, and even low-sodium varieties. Shouldn’t tomatoes have been low-sodium from the start? Who needs high-sodium canned tomatoes anyway?

'Variety is introduced to disguise the fact that food is processed,' says Freedman. 'It shifts attention away from the reality that industrial food loses some of its flavor and freshness simply because it’s been processed.'

The state of American food today

Today, we consume a vast array of foods, both processed and fresh, familiar and foreign. Our love for food is reflected in the global rise of food television, culinary magazines, museums, and exhibitions, a worldwide cultural trend.

'Food brings people together,' says Catherine Piccoli, Acting President of the Museum of Food and Drink. 'It also serves as a means for us to understand one another better.'

Freedman discovered through his research that during the mid-20th century, visitors from around the world were amazed by the incredible range of flavors in American supermarkets. While this diversity is now widespread, many historians believe it began in the U.S. Americans have always been eager to experiment with new foods, both at home and in restaurants.

'A defining feature of American cuisine is its diversity, and this diversity is marked by a sense of enthusiasm,' says Freedman. 'Americanization hasn't spread through McDonald's, but through a love for eclecticism.'

Evaluation :

5/5