Colorado couple’s two-decade quest to rediscover a lost fruit ends in triumph

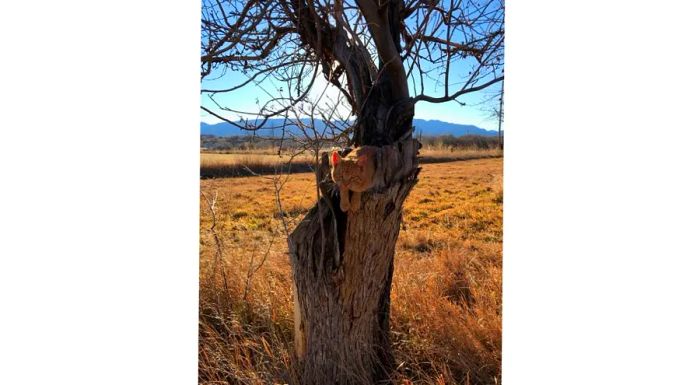

On a chilly December afternoon, as the sun dipped behind the majestic Sawatch Range, Addie and Jude Schuenemeyer gazed at a nearly lifeless tree, its few remaining apples clinging to the last viable branch.

'In that moment, I felt a surge of hope,' reflects Addie.

But was this the moment when their almost two-decade search for a fruit believed to be extinct finally found its end?

'We knew it was something special,' Addie recalls of the discovery.

Colorado is known to be a challenging environment for growing fruit. The state's high altitude and sharp temperature swings in spring and fall create difficulties for farmers trying to cultivate apples, peaches, pears, cherries, and plums.

Yet, despite the thin air, late-season frosts, sporadic rainfall, and grasshopper invasions, fruit orchards have flourished in Colorado’s valleys for generations.

'When the gold rush drew miners to Pike's Peak in the late 1800s, some people recognized that these miners would need to be fed,' says Jude, Addie's husband and co-director of the Montezuma Orchard Restoration Project. 'Others thought they were crazy for even considering that fruit could be grown here,' he adds.

In 2001, the couple founded the Montezuma Orchard Restoration Project (MORP) after acquiring a nursery. Their goal was clear: to establish a genetic repository of Colorado's heirloom apple varieties and reintroduce these species into modern orchards.

'Protecting the genetic diversity of apples is not just important for history, it also offers a crucial resource for today’s farmers and consumers,' explains Addie.

'These apple varieties present a real economic opportunity for farmers in rural Colorado to restore orchards in historic regions and build livelihoods based on the exceptional fruit that once defined our state,' Jude adds.

One of the key varieties the Schuenemeyers aimed to save was the Colorado Orange apple.

'We first encountered the Colorado Orange at a county fair. From the moment we saw it, we knew it was something special,' recalls Jude. 'It had a remarkable complexity—sweetness paired with a tangy depth. At the time, our assessment was based on what we had read, not yet on what we had tasted,' says the Schuenemeyers.

As industrial farming expanded in the early 20th century, the demand grew for fewer, more standardized apple varieties, often cultivated in more temperate climates.

'When the Red Delicious apple was introduced around 1900, it was just one of many apples. By 1920, however, it had become the dominant variety,' explains Jude. 'It was a glossy red apple that thrived almost everywhere. While Colorado could produce a higher quality Red Delicious, the state couldn’t grow as many due to its increased frost sensitivity.'

Over time, orchards that once cultivated a diverse range of apple varieties gradually began to disappear.

'We’ve identified over 400 different apple varieties that were once grown in Colorado, and about half of them are now considered lost,' says Addie. 'The Colorado Orange apple was one of these varieties.'

For years, the Colorado Orange apple was thought to be extinct.

The quest to locate the Colorado Orange apple has become an obsession.

While researching apples historically grown in Colorado, Jude and Addie came across a reference to the Colorado Orange in an old county fair record, noting it had won several awards. However, the origin of the apple was unclear. In the late 1800s, apples were cultivated across the entire state—from the Denver metro area to the far southwest in Montezuma County, where the Schuenemeyers now live.

They had no clear starting point for their search.

'It took us a few years to figure out what it was, where it came from, and then we spent countless hours searching for it,' says Jude.

After digging through state horticultural records, they pinpointed that the variety was first planted in Fremont County, roughly a two-hour drive south of Denver.

Countless trips to the county, talks with farmers, and examining potential Colorado Orange apple trees led to no success, leaving them disappointed each time.

In December 2017, while returning samples from other trees to a man in Fremont County, he offered to show the Schuenemeyers another tree in his orchard—one that his father-in-law had once claimed was a Colorado Orange.

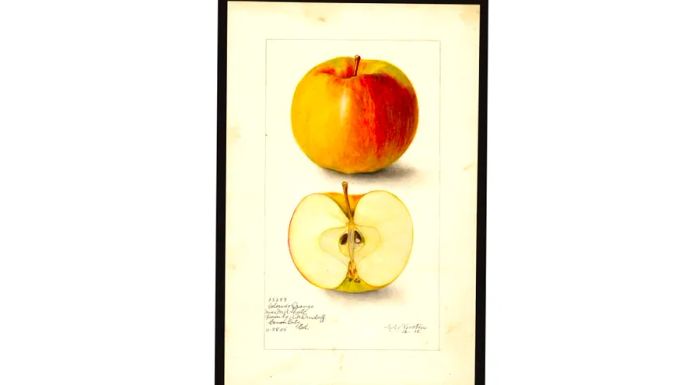

'This orchard was exactly the right age and location where we thought we might finally find this rare apple,' says Addie. 'The apples were just right: round, ribbed, with yellow and orange hues, clearly a late-season variety. We realized the previous tree he had shown us wasn’t the right one, but this one… this one seemed promising.'

Apples to Apples

The Schuenemeyers gathered several apples that were hanging from the tree and scattered around its base. While they had been let down before, they cautiously nurtured their excitement as they set out to confirm if they had finally found what they were searching for.

The couple’s next move was to dive into the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s collection of pomological watercolors. With nearly 4,000 apple paintings, they found four that depicted the Colorado Orange variety. The Schuenemeyers sliced open their apples and compared them to the artwork, and the resemblance was striking.

DNA samples from both the apples and the tree were sent to horticultural scientists at the University of Minnesota, where they were cross-referenced against a comprehensive apple variety database.

Over a year after their initial discovery, the Schuenemeyers received the DNA results: 'unique, unknown.' The apples from Fremont County didn’t match any of the thousands of apple genotypes in the scientists’ database. It was a positive outcome.

'There was no comparison,' Jude explains. 'They didn’t have any DNA for the Colorado Orange because it was thought to be extinct.'

However, Jude and Addie weren’t ready to announce that the so-called extinct apple was actually still alive. They needed more evidence to confirm their discovery.

The day before they received the DNA results, Addie and Jude got an email from a Colorado State University archivist in Fort Collins. She had potentially uncovered a critical clue in unraveling the mystery of the Colorado Orange apple.

'We learned about a collection of wax apple replicas stored in boxes in the office of a retiring professor,' recalls Linda Meyer, the CSU archivist. 'And among them was a listing for the Colorado Orange apple.'

The Schuenemeyers knew this could be the breakthrough they had been searching for. 'This was our chance to finally compare apples to apples,' says Jude.

It took nearly seven months before Jude and Addie could make the eight-hour journey from their home to Fort Collins to meet with Meyer.

They were excited to view the wax apple collection created in the early 1900s by Miriam Palmer, a former professor at CSU. Palmer had been commissioned by the agriculture department to craft wax replicas of the state’s finest and most awarded apples. Each one was carefully sculpted, painted, and numbered for reference.

'Palmer etched a small number on the underside of each apple,' explains Meyer. 'She then attached a card with that number, identifying the apple, its originating orchard, and the year it was collected.'

Among the 83 apples in the collection was number 30 — the Colorado Orange. After the Schuenemeyers compared the wax apple with the ones they had found on the tree two years earlier, they knew they had finally made their discovery.

'We're 98% sure, give or take 3%,' says Addie. After nearly 20 years spent traversing Colorado, searching for a long-lost piece of history, the Schuenemeyers had finally found the proof they were looking for.

'The Colorado Orange is the most incredible discovery we've ever made,' declares Jude.

An apple with a rich history

Since making their discovery, Jude and Addie have collected samples from the ancient tree and have started cultivating new Colorado Orange apple trees.

'We are the recipients of a gift that was passed down from 150 years ago,' says Jude. 'However, it’s not enough for us to be the only ones growing the Colorado Orange. Our goal now is to share it with others.'

The Schuenemeyers have already distributed some of their new trees to six Colorado farmers, who plan to plant and graft them into larger orchards. Their vision is that, within the next five to ten years, the Colorado Orange apple will be available in grocery stores, farmers markets, and restaurants for everyone to enjoy.

'This apple has a rich history,' says Steve Ela, a fourth-generation fruit grower in Hotchkiss, Colorado, who received some new Colorado Orange trees this spring. 'You need to excite people about it—it's local, rare, and it matures late in the fall. That makes it valuable.'

With growing concerns about climate change and the global pandemic, Ela believes consumers are increasingly interested in produce grown closer to home. And he’s confident that if demand for Colorado apples rises, grocery stores will want to stock more of what’s coming from his orchards.

'This is a commodity market, and we can’t match the scale of China or Washington,' says Ela. 'But there are people who truly care about the flavor of their food and seek something unique. With something like the Colorado Orange apple, we stand out because we're the only ones offering it.'

Evaluation :

5/5