Costa Rica Is Taking Significant Steps to Safeguard Its Waters. Are They Effective?

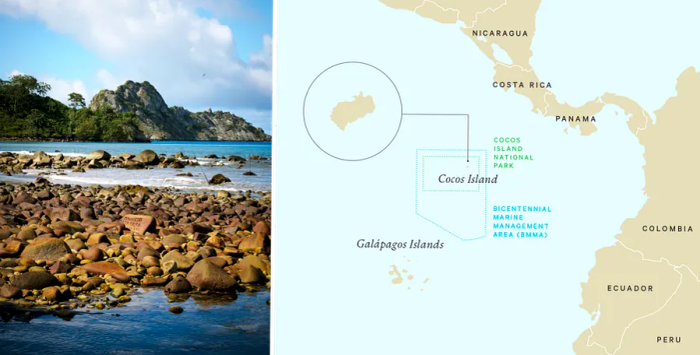

In the turquoise waters approximately 330 miles from Costa Rica’s Pacific coastline lies one of the most untouched islands on the planet. Covering nine square miles, this rectangular landform is known as Isla del Coco, or Cocos Island. A cloud forest thrives there. Water cascades from steep cliffs into swift rivers, and rain-drenched jungles are home to around 400 species of insects and 156 bird species, including the endemic Cocos finch. In 1978, Costa Rica designated Cocos Island and its surrounding waters as a national park. Today, it remains uninhabited aside from park rangers, paramedics, and volunteers. It is so isolated that, aside from the pigs, deer, cats, and rats introduced by humans since the 16th century, no native mammals exist.

Photo by Katie Orlinsky

Cocos is highly esteemed for its extraordinary marine biodiversity. Within its chilly, nutrient-rich underwater pathways, where two currents intersect, a multitude of species such as manta rays and sea turtles swim gracefully. However, the true highlights of Cocos Island are its sharks. Often referred to as “Shark Island,” it is located in waters that harbor some of the largest populations of critically endangered scalloped hammerhead sharks; its depths also accommodate the massive whale shark, along with tiger, thresher, and silky sharks. The legendary French ocean explorer Jacques Cousteau, who conducted numerous dives in the tumultuous waters around Cocos starting in 1976, is said to have described it as the “most beautiful island in the world.” UNESCO designated Cocos Island National Park as a World Heritage site in 1997, highlighting its “irreplaceable global conservation significance, showcasing what portions of tropical oceans once resembled.” The acclaimed marine biologist Sylvia Earle, founder of the nonprofit Mission Blue, named Cocos Island one of her Hope Spots for ocean conservation.

In December 2021, the island captured environmental headlines: Costa Rica announced it would expand Cocos Island National Park to 27 times its original size. This move could allow the country’s endangered sharks—crucial players in the ocean’s intricate ecosystem—to thrive, as their migratory routes to the Galápagos and other regions would be safeguarded against poaching, overfishing, and pollution. Together with the Bicentennial Marine Management Area (BMMA), this expansion would protect over 62,000 square miles of ocean.

Photo by Katie Orlinsky

Ocean activists around the globe celebrated. Costa Rica was set to be among the first nations to support the United Nations’ initiative to protect 30 percent of the world’s oceans by 2030. (To meet this goal, the U.N. suggests that each coastal nation designate 30 percent of its waters for conservation; currently, less than 8 percent of the world’s oceans are safeguarded.) Just a month earlier, at the U.N. Climate Change Conference, Costa Rica, Panama, Colombia, and Ecuador made headlines by pledging to jointly conserve at least 125,000 square miles in the Eastern Tropical Pacific, a hotspot of biodiversity. As a water enthusiast, I too was thrilled by this announcement.

However, the ambitious project of marine protection around Cocos Island was far more complex and fraught with challenges than it seemed at first. It involved not only environmental advocates, various scientists, and Costa Rican NGOs but also the private sector, tourism officials, the Costa Rican Institute of Fisheries and Aquaculture (INCOPESCA), and three presidential administrations. Most importantly, it disrupted a vital migration route, failing to connect Cocos to Ecuador, thus putting some of the ocean’s most endangered species at risk. As I tried to unravel the complexities, I found myself questioning whether the expansion of protection was a true beacon of hope and goodwill. In 2022, I traveled to Costa Rica to discover the answer.

Here’s the reality: I never made it to Cocos Island. I attempted to reach it, but the island’s breathtaking seclusion makes access challenging. Getting there requires a 36-hour boat ride from the port city of Puntarenas. A permit is necessary, and tourism beyond hiking is restricted. There are no lodges or campgrounds available. In 2021, the park welcomed just 2,572 visitors. In contrast, Manuel Antonio National Park, a lowland forest bustling with howler and white-faced capuchin monkeys on the Pacific coast, attracted over 300,000 guests.

Instead, one morning in the coastal haven of Santa Teresa, I meet Carolina Ramírez, a scuba diving instructor and founder of Unidos Por Los Tiburones (United for Sharks), an educational initiative dedicated to Costa Rica’s sharks. Ramírez, whose passion for these ancient creatures emerged in the Pacific’s rolling waves, has dived into the waters surrounding Cocos Island countless times. As we sit at an outdoor café chatting about Costa Rica and conservation, a procession of ATVs and motorcycles passes by, carrying dogs, surfboards, and small children.

Smaller than West Virginia, Costa Rica covers just 0.03 percent of the Earth’s land area but boasts 5 percent of the planet’s biodiversity. Its policies are celebrated as a global benchmark for sustainable tourism, thanks in part to the Costa Rican government’s long-term vision and the efforts of numerous environmental and scientific NGOs and startups that recognized ecotourism as essential for the country’s economic sustainability.

Over fifty years ago, Costa Rica was decimating its tropical rainforests, experiencing one of the highest deforestation rates on the planet—nearly 50 percent. This alarming news attracted a wave of international researchers and environmentalists to the country, raising global awareness of its stunning landscapes and wildlife. Álvaro Ugalde, a biologist known as the father of Costa Rica’s renowned national park system, played a crucial role in the country’s transformation towards nature conservation: In 1970, he and scientist Mario Boza persuaded the government to establish the nation’s first national park, Poás Volcano, located in central Costa Rica.

Photo by Katie Orlinsky; Map by Leo Jung

Gradually, small eco-tourism businesses emerged, offering accommodations and wilderness adventures, attracting visitors and generating employment. As ecotourism thrived, Costa Rica’s economy benefited significantly. In 1997, the government also initiated payments to farmers for tree conservation. Consequently, in 2011, Costa Rica became the first tropical nation globally to successfully reverse deforestation. By twelve years later, over 25 percent of the country was designated as protected parks and nature reserves.

Slowly, Costa Rica shifted its conservation efforts toward its marine environments, which are ten times larger than its land area, housing 85 of the 6,778 marine species that are unique to the region. By 2012, the country had established 166 marine protected areas, covering half of its coastlines. However, in Costa Rica, where over half of the 99 species of sharks and rays are threatened with extinction, sharks have remained a contentious topic, symbolizing the struggle to balance conservation with the need for a sustainable fishing industry. (Although current president Rodrigo Chaves Robles signed an executive order in February 2023 banning hammerhead shark fishing, many sharks still face threats and can be caught by longline fishing vessels due to a legal loophole regarding “accompanying fauna.”) Ramírez states: “Everyone views sharks as the enemy, the monsters of the ocean. People fail to recognize their importance. We need to present sharks as the most magical, curious, and amazing creatures on the planet.”

Ramírez explains that if sharks are overfished, it negatively impacts other fish species that fishermen depend on, such as tuna and snapper. Scientific research backs this up: As apex predators, sharks play a crucial role in managing other fish populations and ensuring their growth. They are vital for maintaining healthy oceans. There is also a strong financial argument for protecting sharks. During a single season at Cocos Island, activities like diving, snorkeling, and boat tours generate enough revenue that one hammerhead shark can be valued at approximately $86,000. Over two decades, this amount totals $1.6 million, according to the nonprofit organization Mission Blue.

People often overlook their significance. We should celebrate sharks as some of the most magical, curious, and incredible creatures on Earth.

Photos by Katie Orlinsky

Conservationist Randall Arauz has the rugged appearance of someone who spends his life at sea. As one of Costa Rica's prominent scientists, Arauz is a founding member of MigraMar, a nonprofit focused on studying endangered marine migratory species in the Eastern Pacific. He also serves as the international marine conservation policy advisor for Marine Watch International, dedicated to ocean protection. Arauz has visited Cocos Island 55 times and completed over 1,000 dives in its waters, tagging numerous sea turtles, manta rays, and sharks.

On a steamy Monday morning, after a two-hour journey from San José, Arauz and I reach Tárcoles, a quaint fishing village located in the Gulf of Nicoya on the Pacific coast. The shore is bustling with a dozen or more individuals, their vibrant boats strewn across the sandy beach. Thousands of Costa Ricans rely on fishing for their livelihoods, targeting seasonal fish populations like mahi-mahi, tuna, and red snapper. As the nation moves towards safeguarding its marine environments, these fishers are also grappling with the challenges of transitioning to more sustainable fishing methods.

Dressed mostly in T-shirts, sandals, and shorts, the fishermen have just returned from the ocean and are now tidying up. A young man with a dark beard, shirtless and adorned with tattoos cascading down his arms and chest, is meticulously winding a long nylon fishing line. Another fisherman stands at a weathered wooden table, machete in hand, expertly slicing large tuna into uniform, cherry-red steaks. An older man named José, with whom we converse in Spanish, shares that he used to sell hammerhead sharks when other fish were hard to find. However, upon learning about their endangered status, he stopped. When we inquire about the impact of overfishing on their livelihoods, some men express concern while others hesitate to voice their worries.

As the national park expansion was underway, Arauz served as the secretary of the official Cocos Island Marine Management Council. However, before the finalization of the park boundaries in 2015, Arauz and a team of scientists made a pivotal discovery: instead of migrating through the marine corridor to the Galápagos, some critically endangered sharks were journeying between Cocos Island and the seamounts (underwater mountains) of Las Gemelas and West Cocos, likely traveling to forage. This finding indicated that the seamounts where the sharks gathered should be incorporated into the new marine sanctuary. Other research, including studies from the University of Costa Rica, supported their findings. Despite this, when Arauz petitioned government officials to include the seamounts, he was disregarded. Frustrated that the corridor was omitted, he resigned from the council. “While we achieved a larger national park, there was no swimway,” he expressed. “How can we protect these creatures if we don’t safeguard their migration route?”

Photo by Katie Orlinsky

Carlos Alvarado Quesada, the former president of Costa Rica who enlarged the boundaries of Cocos Island National Park and the BMMA, acknowledges the complexity of negotiations surrounding the reserve. “This journey was far from straightforward,” Alvarado, now a professor at Tufts University, remarked. “However, strategic investment is essential. I believed that the most significant impact we could make was at Cocos Island. The boundaries were established based on the best scientific knowledge available at that time.” Previously, less than 3 percent of Costa Rica’s ocean was designated as protected from fishing. Now, 30 percent of its marine territory is safeguarded. “This ensures a future for countless species,” he affirmed.

One afternoon in San José, I meet with Iria Chacón, a biologist and conservation manager for Friends of Cocos Island (FAICO), an organization established in 1994. FAICO, a small but dedicated Costa Rican group focused on marine conservation, played a key role in the establishment of the Cocos Island and BMMA reserves. For two decades, it has consistently supplied resources to Cocos Island—rain gear, educational materials, and conservation strategies. We gather around a light-colored wooden table in a conference room, with three vibrant photographs of Cocos Island adorning the azure walls.

Chacón played a key role in shaping the expansion plan for Cocos Island National Park, striving to accommodate the diverse interests of park rangers, fishers, and environmental advocates. Although she welcomed the enlarged national park, she was open about the compromises made in the BMMA. To support local fishing communities, sustainable fishing practices for species like tuna would be permitted, which poses a risk to endangered sharks. She acknowledges it as a necessary compromise. “Finding a balance is essential,” she states. “We need no-take zones in the ocean free from fishing, but we must also be pragmatic. Many communities depend on that resource.”

Photo by Katie Orlinsky

Research indicates that no-take marine protected areas can actually enhance fish populations and biodiversity. Following then-president Barack Obama’s decision to more than quadruple the size of Hawai‘i’s Papahānaumokuākea Marine National Monument in 2016, yellowfin tuna catches surged by 54 percent outside the reserve, while bigeye tuna catches increased by 12 percent. There is optimism that by restricting fishing within the BMMA and prohibiting it in the national park, this segment of Costa Rica’s economy will thrive. A broader transformation is also in motion, albeit gradually: Since 2019, supported by the World Bank, the country’s fisheries agency, INCOPESCA, has been executing a $90 million initiative to promote sustainable fishing nationwide.

Photo by Katie Orlinsky

In September 2021, Costa Rica pledged to partner with the nonprofit MarViva to enhance research and monitoring efforts on Cocos Island. The country also entered into a five-year agreement with U.S.-based WildAid, a conservation organization, to improve surveillance in marine zones. Now, they face the task of developing a comprehensive management plan for the reserves.

The sheer scale of Cocos Island’s marine protected area is impressive. To combat illegal fishing, the government will need to invest millions in technology, surveillance, and law enforcement, along with hiring additional park rangers for sea patrols. Currently, the park has around 20 rangers. Compounding the issue, these rangers often struggle with basic supplies, such as a steady fuel supply for their patrol boats. As a result, while they may observe poachers, they typically lack the means to apprehend them—or to chase down industrial fishing vessels due to speed limitations. Human-induced threats, including climate change, oil spills, plastic pollution, and habitat degradation, further complicate matters. Chacón emphasizes the need for Costa Rica to conduct more extensive research within the marine reserves and gather more data on its rich marine life to effectively safeguard their habitats.

Photo by Katie Orlinsky

In June 2022, Costa Rica received encouraging news regarding funding for its environmental initiatives: The Bezos Earth Fund announced a grant of $30 million to be shared among Costa Rica, Panama, Ecuador, and Colombia—nations bordering the Eastern Tropical Pacific—aimed at linking and protecting marine reserves, thereby safeguarding life in the corridor.

Despite its small size, Costa Rica stands as a guiding example for other nations regarding the significance of environmental preservation. However, everyone I talk to underscores that efforts to protect the waters around Cocos Island and within the BMMA are just beginning. Chacón highlights the need for more sustainable fishing practices and stricter regulations. "The successful implementation of marine protected areas will require extensive monitoring," she states. "At some point, we need to show that these areas are effective, both to inform Costa Ricans and to share with other countries."

1

2

3

4

5

Evaluation :

5/5