Experiencing Mexico City Through Frida Kahlo’s Perspective

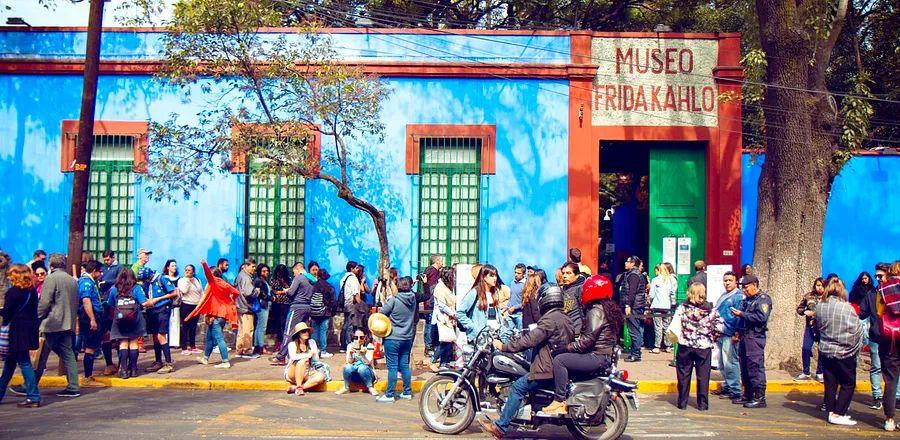

Casa Azul—known as the Frida Kahlo Museum on Google Maps—nestles at the intersection of Londres and Ignacio Allende in the serene, upscale neighborhood of Coyoacán in southern Mexico City. This colonia is celebrated for its tree-lined streets, vibrant market, and as the former residence of the nation’s most famous artists: Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera. Casa Azul served not only as their shared home (and briefly that of the exiled Leon Trotsky) but also as the birthplace and final dwelling of Kahlo herself.

About a month before my initial visit to Casa Azul in October 2019, I suffered a severe trimalleolar ankle fracture from a rather foolish accident that effectively detached my foot, landing me in a rather dubious hospital for two weeks where no one spoke English. I underwent a harrowing surgery amid a painkiller shortage and shared some of the most profoundly human experiences of my life with fellow patients in the broken bone ward. But that’s a different story altogether. Suffice it to say, by the time I arrived at Frida’s, my body and mind were in a state of post-traumatic recovery.

I hadn’t yet mastered the transition from taxi to wheelchair, which always felt uncomfortable and embarrassing. However, once I was settled in my mobile throne and rolling alongside Casa Azul’s striking cobalt walls, a sense of calm enveloped me. The relaxed atmosphere of Coyoacán provided a soothing escape from the frantic pace of the megacity. At that time, I lived on the bustling Nueva Leon thoroughfare in Condesa, where chaos from commuters was nearly constant. Here in the tranquility of Coyoacán, though, there were few vehicles—mainly a handful of buses and taxis dropping visitors off at the museum.

Visitors formed a line that wound along the wall and around the corner, occasionally crossing the street to grab a refreshing drink from one of the many street vendors in Mexico City. I was the only person in a wheelchair, and I found myself contemplating what it must have been like for Frida to navigate the city’s cracked and uneven streets during the later years of her life, rolling and using crutches before her condition confined her within the walls of Casa Azul.

My girlfriend nudged me to the back of the line, and we enjoyed the pleasant, quiet sunshine while waiting for our turn to enter. Subsequent visits confirmed that there’s always a queue, even though you must purchase tickets for a specific time online before arriving. (A quick tip: Make sure to buy your tickets several days in advance, as every time slot tends to sell out.) Tickets cost $250 pesos (about US$13), and once inside, you can buy a photo pass for $30 pesos, allowing you to take pictures.

I was the only person in a wheelchair, and I couldn’t help but reflect on what it must have been like for Frida to navigate the city’s cracked and uneven pavement in the later years of her life...

Once inside the compound, I rolled through the main house, which showcased a wide array of works, photographs, letters, and artifacts related to Kahlo’s life. It’s fascinating material, definitely worth the time to explore. However, it was, ironically, quite challenging to see everything from a wheelchair.

What’s the irony? Those who know Frida Kahlo’s story may recall that she contracted polio as a child and later endured a horrific bus accident that left her body shattered, resulting in a lifetime of pain and reduced mobility. By the end of her life, she relied almost entirely on a wheelchair for movement.

Yet, it turns out, Casa Azul is nearly comically inaccessible for individuals with disabilities.

At the entrance to the house, there’s a ramp next to a few stairs. So far, so good. However, once I entered the initial hall, things became challenging—especially from a wheelchair perspective.

Leaving the photo gallery behind, I rolled into a vibrant room filled with an eclectic collection of ceramic art by Frida, Diego, and others. To move further, though, I faced the daunting task of navigating stairs. I managed to descend the few steps to admire a charming kitchen adorned with Frida and Diego’s names, but to reach the main studio—arguably the highlight of the house—I had to conquer a dozen or so more stairs. Unfortunately, wheelchairs aren’t permitted at the top.

So.

At the base of the stairs, I was informed that I would either need to hop my way up and retrieve my chair on the other side or forgo it altogether. But I’m a determined soul, so hopping it was. And hop I did.

At this point, my ankle bones had barely started to heal. Without a cast, they were held together by an assortment of screws and steel plates, and they still wobbled and grated whenever I moved too suddenly. As it turns out, jumping up a dozen or more stairs and then traversing a crowded museum involves an excessive amount of sudden movement. The result? Pain. Teeth-grinding, sweat-inducing pain.

Photo by Alexandra Lande/Shutterstock

I was relieved I tackled the grueling ascent, for I discovered some truly captivating items that made the effort worthwhile. In the studio, an assortment of artistic tools—palettes, brushes, small jars of paint—was displayed in front of an easel that was clearly used by Frida, not Diego. How can you tell? The wheelchair positioned in front of it.

There’s something both humbling and inspiring about that empty wheelchair, even if you’re not using one yourself. It speaks volumes about the challenges Kahlo faced for her art, a poignant reminder of the great artist who once occupied it.

Recently, I had a conversation with author Chloe Cooper Jones, whose memoir Easy Beauty explores her experiences as a traveler living with a rare congenital disorder called sacral agenesis (which means she was born without a sacrum or lower lumbar spine, leading to mobility challenges and chronic pain). Our discussion eventually turned to Frida Kahlo.

“What I find incredibly inspiring about her,” Cooper Jones remarked, “and something I would express gratitude for is how she weaves all those painful experiences—struggles and difficulties—into her art. They’re fully integrated into her self-portraits and reflections. They aren’t concealed or viewed negatively; rather, they are essential elements of self-exploration.”

The ability to flourish and succeed not in spite of one’s challenges but because of them embodies the kind of antifragility that has shaped many of history’s most significant artists and masterpieces.

“When we observe how people present themselves on social media, there’s immense pressure to mask what might be perceived as struggle, difficulty, or difference,” Cooper Jones continued. “It’s as if we want to erase those aspects of our lives, showcasing only filtered, carefully curated images that radiate positivity. Yet artists like Frida Kahlo embraced their realities—she incorporated her leg braces into her artwork! She depicted her pain, her miscarriages, and her back braces. All these elements are vividly present, forming a vibrant and complex individual. The most fascinating part is that when viewers engage with her art, they feel deeply connected to her vision, far more so than with a polished, airbrushed portrayal.”

After exploring the studio, I entered the bedroom where Frida spent her last days. Inside was a simple bed, with a death mask resting on the comforter. Above the bed hung a painting of a deceased infant, and at its foot was the mirror she used for her self-portraits. Leaning beneath the mirror were a pair of crutches.

Gazing at those unassuming wooden crutches stirred a whirlwind of emotions within me. To achieve such artistic and sociopolitical greatness while enduring physical challenges that many would consider insurmountable—what an extraordinary human she was! And why hadn’t I brought my own crutches? Who would have thought that Frida Kahlo’s home would present such a physical challenge?

In the last room, a collection of Frida’s personal belongings and a ceramic urn containing her ashes can be found. The urn is surprisingly modest, and I didn’t even realize what it was during my initial visit—perhaps because the room was packed, and I was eager to find a seat. So, I hopped down the stairs and exited into the garden where my wheelchair was waiting.

The garden offers a serene escape, even amidst the crowd of tourists snapping selfies. It’s easy to see how this space could foster reflection and creativity. Verdant plants flourish within the cobalt and granite walls, while frog mosaics adorn the pond bottoms. Strange, red, featureless faces and rugged figures are sculpted from clay, and there’s a cluster of conch shells alongside a red pyramid embellished with ancient ruins.

At the back of the garden, an exhibit showcases Kahlo’s vibrant traditional dresses alongside an array of medical devices: crutches, harnesses, corsets, jars of bandages, and a blood-stained hospital gown. This entire display unintentionally symbolizes her iconic work, The Two Fridas: one side bursting with color and life, the other stark and vulnerable, heart exposed and bleeding.

The Two Fridas is currently displayed at the Museo de Arte Moderno, situated at the edge of the expansive Chapultepec park. It ranks among my favorite art museums worldwide.

The museum is surrounded by a garden featuring abstract and surrealist sculptures, and its interior is divided into two levels connected by a double-helix staircase. The permanent collection is located upstairs, where you can find Las dos Fridas.

It’s now May 2022, and I’ve just arrived at the MAM after spending the morning at Casa Azul. So much has changed in the two and a half years since my first visit. This time, I’m on my own two feet, albeit with a slight limp.

Much of the museum is dimly lit, but the permanent collection is accessible. At 11 a.m. on a Tuesday, there’s hardly anyone around. It’s just me, a friend, and a small tour group of locals. The group moves steadily through the gallery but pauses before The Two Fridas as their guide elaborates on the painting’s importance. It’s no wonder it draws extra attention; it’s one of Mexico's most celebrated artworks and a centerpiece of the museum's collection.

Photo by Nick Hilden

One Frida, adorned in traditional Tehuana attire, with a vibrant heart and a joyful demeanor, holds in one hand a small portrait of her recently (but temporarily) divorced husband, Diego. In her other hand, she grasps the hand of another Frida, who wears a pale European dress, her heart exposed and bleeding, with a vein spilling blood onto her skirt as she tries to staunch the flow. The two Fridas are connected by a vein running between their hearts, illustrating a poignant portrait of duality and pain; loss and resilience.

"The creations she left behind will endure forever," Cooper Jones remarked to me later. "She’s captured something immensely valuable for so many. I believe that wouldn’t have been possible if she hadn’t been able to reveal all those facets of herself."

As I stood before the Fridas, I realized I had gained a deeper insight into her than I did three years prior, before the accident. Or maybe it was the other way around; perhaps Frida understood something about all of us, which is what made her remarkable.

Frida Kahlo recognized that everyone experiences pain, that we all have wounded hearts and face struggles while questioning our reflections. This empathy is crucial to her greatness, but more importantly, Kahlo understood something often overlooked: there can be grace in suffering and beauty in hardship.

Continue reading: The 10 Best Hotels in Mexico City

1

2

3

4

5

Evaluation :

5/5