Exploring the final resting place of Tutankhamun’s treasures

For nearly a century, King Tutankhamun has been the face of Ancient Egypt. His death mask, an exquisite masterpiece crafted over 3,300 years ago from 24 pounds of hammered gold, adorned with lapis lazuli eyeliner and eyes made of quartz and obsidian, continues to captivate the world.

It is arguably the most iconic artifact from the ancient world.

Once sealed within Egypt's Valley of the Kings, the mask has since traveled the globe, mesmerizing audiences with its lavish beauty and the timeless enigma of Egyptian royalty.

“If you ask any child, even as young as eight, and mention Egypt, they'll immediately think of King Tut,” says Zahi Hawass, an Egyptian archaeologist and former Minister of Antiquities. “Just last week, I did a Skype call with a school in the States, and all the kids asked about one thing: Tutankhamun.”

While the ancient Egyptians constructed towering monuments for their departed, such as the grand Pyramids at Giza, modern Egyptians are creating a new sanctuary for Tutankhamun and his ancestors just over a mile away.

A monumental structure made of glass and concrete, a masterpiece of modern design.

After eight years of construction and numerous delays, the Grand Egyptian Museum lives up to its name — it’s truly ‘grand.’

Spanning nearly half a million square meters, the Grand Egyptian Museum is as vast as a major airport terminal, with a hefty price tag to match. A significant portion of the funding has been covered through loans from Japan.

Egypt is eager to restore its tourist industry to the levels seen before the political turmoil that followed the 2011 Arab Spring.

This is meant to be their eternal resting place.

Was he the product of incest?

Since the 1960s, a collection of Tutankhamun’s treasures has toured the world intermittently. Among these relics is the ‘Guardian Statue’ of the Boy King, a striking figure with a black-painted face and body symbolizing the rich, fertile silt of the Nile.

One of the golden statues depicts Tutankhamun holding a harpoon while wearing one of his many crowns. On the back of a golden throne, the young king is portrayed with his queen, both bathed in the sun’s rays in a tender marital scene. Additionally, a golden fan shows him hunting from his chariot.

Tutankhamun’s image was always idealized, much like the portrayal on his famous death mask.

However, the reality of his life might have been quite different.

The first images of his unremarkable mummy, revealed in 1925, suggest that Tutankhamun may have been the product of incest. Standing about 1.65 meters (5 ft 5 in), he likely suffered from a clubfoot and had pronounced buck teeth.

He died young, at 18 or 19, and Egyptologists continue to debate the cause of his death.

“When you delve deeply into the collections and history of the king, you realize just how significant he was,” says Tayeb Abbas, head of archaeology at the Grand Egyptian Museum.

“What makes the king so intriguing is that both his life and death remain a mystery. That’s why people from all over the world continue to be captivated by King Tutankhamun.”

Skeletal remains

The creation of the new museum has taken nearly as long as Tutankhamun’s lifetime. A winning design was selected in 2003, featuring a facade made of semi-translucent stone, stretching one kilometer, which can be illuminated at night.

The original design was created by a small Dublin-based firm, Heneghan Peng, led by Shih-Fu Peng, an architect of American-Chinese descent.

The Egyptian Revolution in 2011 caused delays, and construction didn't truly gain momentum until the following year.

Dinogo first revisited the project six years later, in 2018, as the pyramid-shaped entrance began to take form.

“This is a new landmark added to the iconic view of greater Cairo… for the first time, the pyramids and the magnificent treasures of Tutankhamun will be in direct line of sight,” said Tarek Tawfik, the former director general of the Grand Egyptian Museum Project, at the time.

A visit to the museum in May 2020 showed the site looking nearly ready, with landscaping complete and everything in place.

However, behind the scenes, it was still very much a construction zone – and the ongoing pandemic didn’t make things easier.

Before entering, everyone had to undergo a temperature check, including Dinogo’s team.

Like characters from a new “Ghostbusters” film, groups of workers were seen wearing disinfectant tanks on their backs, spraying the premises.

“We are working tirelessly, despite the challenges posed by Covid-19,” says Major General Atef Moftah, the army engineer overseeing the museum. “We are taking all necessary precautions, sterilizing everything and everyone.”

Pharaohs and deities

On the ground, it’s easy to grasp the sheer scale of this monumental project.

The statue of Ramses the Great, the largest artifact in the museum’s collection, was transported in 2018 to allow the atrium to be built around the 13th century BCE pharaoh.

Standing over 20 meters tall and made from 83 tons of red granite, Ramses is truly magnificent – despite his royal nose being chipped and his stubby toes dusted with a layer of grime.

The new museum offers a much more dignified setting than the polluted area outside Cairo’s central train station, where Ramses once stood.

Ramses’ companions, positioned on a grand staircase behind him, remain mostly concealed for now.

The staircase will feature 87 statues of pharaohs and Egyptian gods. As visitors ascend, they will embark on a sweeping journey through 5,000 years of Ancient Egyptian history.

That is, at least, once the museum finally opens its doors.

“The project is expected to be completed by the end of this year,” says Moftah. “Then, early next year, we will focus on the antiquities section for another four to six months. By then, we hope Covid-19 will be a thing of the past, and the world will be at peace.”

From Dinogo’s brief visit, it’s clear that as work continues to refine the vast spaces, tourists will likely need two full days to explore it all.

Museum with a view

As visitors navigate the museum, they’re likely to encounter a familiar motif that repeats throughout.

Pyramids dominate the space. Whether standing tall or flipped upside down, enormous triangular shapes are embedded in the museum's grand architecture and mosaic surfaces. And then, of course, there are the actual pyramids – visible through massive windows. This truly is a museum with a view.

The Great Pyramid, less than a mile away, is thought to have taken around 20 years to construct. Commissioned by Pharaoh Khufu in the 26th century BCE, it was built as a tomb using more than two million granite blocks, each weighing over two and a half tons.

From the architectural competition to the anticipated opening in 2021, the Grand Egyptian Museum has taken nearly 20 years to bring to fruition.

The museum is undeniably a symbol of immense prestige for Egypt. Alongside the construction, a remarkable initiative is underway to preserve every single one of Tutankhamun’s treasures.

The goal is to showcase all of these treasures together – a first in history.

‘A display of death’

The Conservation Center at the Grand Egyptian Museum is the largest of its kind in the Middle East. It stretches into an almost endless corridor, leading to 10 specialized laboratories, each focused on the delicate art of conservation.

The laboratories are surrounded by an almost monastic silence, as the experts inside require utmost concentration, a keen eye, and a steady hand to carry out their work.

There are over 5,000 artifacts from Tutankhamun alone that require conservation. “His stunning collection of death-related treasures,” as Howard Carter, the famed archaeologist who discovered the tomb, once described it.

Many of these items are undergoing fresh conservation work so they can be displayed for the first time when the new museum opens.

Some of the funding for this work comes from Tutankhamun’s golden legacy – the revenue generated from showcasing his treasures around the world.

Revived from the past

In the labs, you'll also find the lion goddess Menhit, her nose and tears crafted from blue glass, with eyes made of painted crystal. There's also the fearsome deity Ammut, part hippo, part crocodile, and part lion, with ivory teeth and a red tongue.

Mehet-Weret, the cow goddess, also makes her appearance here, shown through a pair of bovine figures with solar discs wedged between their horns.

Ritual couches, believed to aid Tutankhamun’s journey to the afterlife, are also among the artifacts. After restoration, they remain in remarkable condition.

It's a rare privilege to view these treasures before they are sealed behind glass in the new museum.

And not all of his possessions were made of gold.

Tutankhamun’s burial included around 90 pairs of sandals, some crafted from rush and papyrus, others from leather and calfskin.

Before restoration, one pair had begun to deteriorate, but even those were able to be preserved.

“We developed a special technique using a unique adhesive,” explains conservator Mohamed Yousri. “Its condition was quite poor, but now it’s almost like new.”

One pair of sandals, seemingly almost brand new, features depictions of captured warriors – one Nubian, the other Asiatic. With these sandals, Tutankhamun could symbolically tread on his enemies daily.

“What we are doing here is rediscovering the king’s treasures,” says Tayeb Abbas, the museum’s head of archaeology. “Our work is as crucial as that of Carter himself.”

A fortunate discovery

At 48 years old, English archaeologist Howard Carter made one of history's greatest discoveries in the Valley of the Kings, a vast burial site on the Nile's west bank near Luxor.

Carter would dedicate the next decade, from 1922 to 1932, to meticulously cataloging the treasures and carefully excavating the tomb.

Had it not been for his relentless pursuit, Tutankhamun’s tomb might have remained hidden. And without that discovery, the Grand Egyptian Museum might never have come to be.

“This king was one of a kind,” says Hawass. “I believe Howard Carter was incredibly fortunate to uncover his tomb. In my opinion, this remains the most significant archaeological discovery to date.”

Carter’s personal archive is housed at the Griffith Institute, an esteemed Egyptology research center at Oxford University in the UK.

A man of precision and high standards, Egyptology owes Carter a tremendous debt. His approach to clearing the tomb set the standard for excavation in his time.

Items like the black and gold Guardian Statue were coated with protective paraffin wax. However, nearly a century later, this wax is now being carefully removed.

During Dinogo's visit, experts were painstakingly removing every trace of wax from a ceremonial chariot, restoring its original gleam.

Meanwhile, Tutankhamun's outer coffin has undergone fumigation to protect it from insects. Conserving this single piece has already taken eight months.

This marks the first time the coffin has left the Valley of the Kings. It won’t be returning, much to the dismay of some people.

“Honestly, most people from the west bank were upset about this,” says Abbas. “But once we revealed the coffin's poor condition, the community began supporting our efforts to restore it to its original state.”

The Curse of the Mummy

The local community did manage to secure one victory—they succeeded in keeping Tutankhamun’s mummy, despite the authorities’ initial desire to transfer it to the new museum, just like the outer coffin.

“The people of Luxor believe their ancestor should remain there,” says Hawass, Egypt’s former minister of antiquities. “And I truly respect this. When we made the decision to move the mummy a few months ago, the entire town opposed it. And honestly, that response made me happy. The mummy will stay there.”

Fifteen years ago, Hawass did manage to bring the mummy out for a CT scan – but it was only for a day, barely enough time to provoke the ‘mummy’s curse’—the deadly legend surrounding the moving of King Tut’s remains. This curse is said to have claimed the life of Carter’s financial backer, Lord Carnarvon.

“When I took the mummy out of its coffin to scan it, I gazed at his face,” recalls Hawass. “That was the most extraordinary moment of my life. The discovery—November 4, 1922, when Carter unearthed 5,398 objects after 10 years of excavation. The curse. Lord Carnarvon’s death. All of it—the magic of King Tut!”

It seems that everything inevitably circles back to Tutankhamun. A century ago, only a handful of Egyptologists knew his name. Today, the whole world knows it.

‘Experience the history’

While the new Grand Museum will undoubtedly secure the legacy of King Tut and many other treasures from Egypt’s past, it’s reassuring to know that part of the nation’s more recent history will also be preserved.

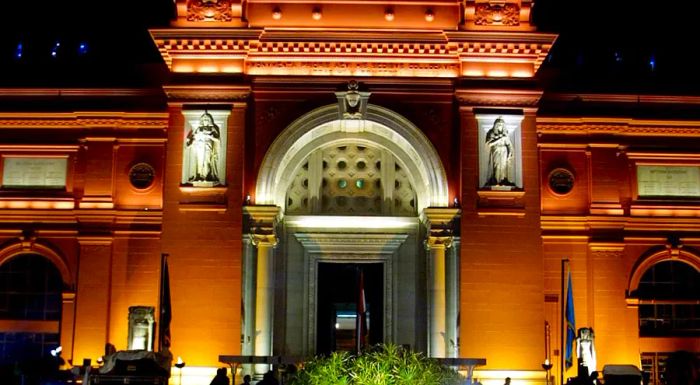

Head into downtown Cairo, and you can’t miss the salmon-hued sandstone structure of one of the city’s most iconic landmarks.

The Egyptian Museum of Antiquities, a favorite of Egyptologists, first opened its doors in 1902.

Inside, you'll find one hall after another, filled with statues and a constantly growing collection. This is the place where you can discover some of the Boy King's family members.

Here you’ll encounter Akhenaten, the so-called ‘heretic’ pharaoh and Tutankhamun’s father. Nearby is an unfinished bust of his stepmother, the graceful Nefertiti. His grandparents, Yuya and Tjuyu, once a formidable power couple, are also on display.

“You know, the Cairo Museum can never be closed, even with the opening of the Grand Egyptian Museum,” says Hawass. “When you step inside, you can almost smell the history, the scent of the past. That's why we preserve it as is.”

Naturally, most visitors head straight to the first floor of the Cairo Museum. That’s where, for now, you can still see the famous death mask and the rest of Tutankhamun’s treasures.

The display has always felt somewhat lackluster. The beautiful but outdated glass cases and the dull lighting don't do justice to the treasures inside.

But let's face it, gold always dazzles, no matter the lighting.

One standout piece is the 22-carat solid gold effigy of Tutankhamun, which formed his innermost coffin. Measuring just over six feet in length, it weighs a substantial 108 kilograms (240 pounds)—about the same as heavyweight boxing champion Anthony Joshua.

Perhaps even more charming is a painted wooden figure of Tutankhamun, likely created during his teenage years. This may have been a model used to showcase his clothing.

Back in the laboratories, researchers are conducting the first-ever scientific analysis of Tutankhamun’s textiles, including a scarf or shawl several meters in length, remarkably preserved for over 3,300 years since his passing.

Unlocking the secrets

This research is part of a collaborative Egyptian-Japanese project.

According to Mia Ishii, an expert in ancient textiles and associate professor at Saga University in Japan, 'Textiles are the most fragile of all the items found in Tutankhamun's tomb. This is why the Egyptian government specifically requested that we focus on preserving these materials from the very start.'

Over 100 textile artifacts were found in the tomb, many clearly used during Tutankhamun's lifetime. Among them is a tunic adorned with a lotus flower design, which in ancient Egypt symbolized eternal life.

Japanese experts have also been crucial in advising on the delicate task of relocating the items – from the Cairo Museum to the new Conservation Center, located 10 miles away.

In 2018, Dinogo observed a ritual couch being carefully wrapped with Japanese washi paper, which was used to reinforce fragile areas of its gold leaf.

A hunting chariot required a custom crate and extensive manpower to move, nearly involving a team large enough to play a football match.

Research has revealed that the chariots of Tutankhamun were crafted from a type of hardwood – elm – which is not native to Egypt. The wood likely originated from the Eastern Mediterranean, more than 500 miles away.

Some artifacts continue to unveil their mysteries. For example, a set of rods covered in gold leaf was initially puzzling, but it is now believed they formed part of the sunshade for a ceremonial chariot – the oldest known sunshade ever discovered.

One remarkable find was a dagger buried with Tutankhamun, made from iron derived from a meteorite. In ancient Egypt, objects from the heavens held special significance.

Another exquisite discovery is a pendant adorned with scarab beetles – a symbol of immortality in ancient Egyptian culture.

Flesh of the gods

In the 1920s, the pendant was photographed around the neck of a young boy who worked to bring water to Carter’s excavation crew. According to the tale, this is the boy who stumbled upon the tomb.

While making space for his large water jar, the boy accidentally uncovered the first step, leading him down a staircase of sixteen steps into the tomb.

His story is set to be featured in the upcoming Grand Egyptian Museum.

At the new museum, the Tutankhamun exhibit is still under wraps. What we do know is that it will be vast, spanning an impressive 7,000 square meters.

The Egyptian authorities are expecting two to three million visitors in the first year, with the long-term forecast reaching seven to eight million. This would place the museum among the top three most visited worldwide.

We know that Tutankhamun's death was abrupt and untimely. In death, the Golden Boy was elevated to the status of a god—gold, for the ancient Egyptians, symbolized the very flesh of the gods.

And of course, it is the allure of that gold that continues to captivate us, undoubtedly drawing many to see Tutankhamun in his new home.

Evaluation :

5/5