Exploring the Pantanal Region of Brazil on a Jaguar Adventure

Just an hour into our Pantanal expedition, the largest tropical wetlands in the world, our guide receives an urgent call from a fellow guide: jaguars spotted. A mother and her cub. We have just five minutes to grab our binoculars and muster our courage before hopping into the jeep, its seating stacked like a theater—eager not to miss our first glimpse of this region's top predator.

Honestly, I’d already had my wildlife moment that day: we encountered capybaras at the entrance of our ecotourism lodge, Caiman. Just beyond the fence meant to keep jaguars at bay, a relaxed group of these giant rodents—like guinea pigs the size of Labradors—nibbled on grass, hardly noticing us. (The closest I’d been to capybaras before was behind the foggy glass at the San Diego Zoo, which made me squeal with delight.)

Then there were the pairs of hyacinth macaws—a parrot relative, impressive in size (over three feet long from beak to tail) and a brilliant cobalt blue—perched in the trees above the lodge's turquoise pool. These magnificent birds often fall victim to illegal trade and habitat loss, with about 10,000 removed from the wild by the 1980s, according to the nonprofit Instituto Arara Azul (Hyacinth Macaw Institute). However, Caiman is dedicated to conservation, partnering with the institute to create an ecological refuge—one of the reasons I’m here.

Photo by Laura Dannen Redman

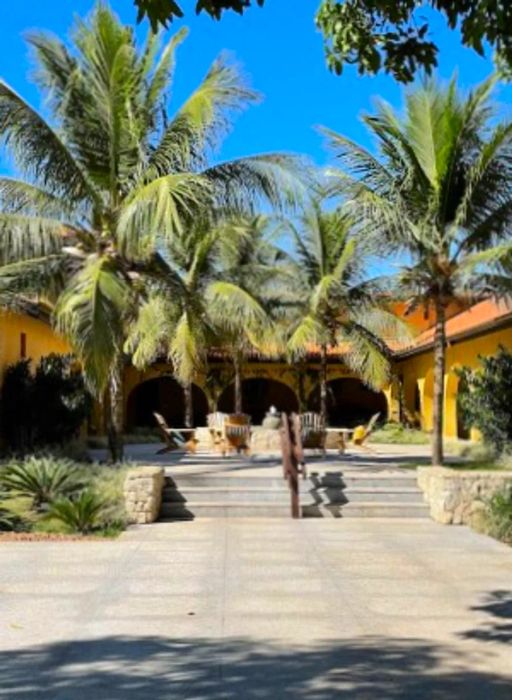

My temporary sanctuary during this May adventure is Casa Caiman, the very childhood home of reserve owner Roberto Klabin. His family has been ranching in the Pantanal since 1952, having initially found success in the pulp and paper industry. Now an entrepreneur and environmental advocate, Klabin cherishes memories of this expansive terra-cotta estancia from the age of 10. Although he doesn't recall encountering a jaguar back then, it’s understandable given the elusive nature of these big cats. Rewilding efforts gained momentum in 2016, yet wildfires and droughts continue to pose threats to the region’s biodiversity.

Estimates vary, but the International Union for Conservation of Nature places the jaguar population in the tens of thousands, categorizing them as a “near-threatened” species. Over half of the world's jaguars reside in Brazil, and for the past decade, the nonprofit OnçDinogoi has collaborated with Klabin and his Caiman Ecological Refuge to monitor and rehabilitate these magnificent mammals, ensuring they can thrive and reproduce in their natural habitat. Since 2016, three female jaguars have welcomed 15 cubs, including the duo we’re currently tracking.

****

Living in an urban jungle—like New York City, where the wildlife is often limited to vermin stealing pizza slices into the sewers—can make it a surprise to see so many species of mammals, birds, fish, and reptiles casually around, so near to home. Caiman shares the same time zone as New York, just a straight shot south across different hemispheres and seasons. It takes about 11 hours and three flights on progressively smaller planes—an international jet, a domestic airline, and finally a propeller plane—to reach the wetlands. In contrast, an African adventure for an American might require a day and a half of travel just to enjoy a welcome cocktail. Yet here I was, free of jet lag, speeding in a jeep down a hard-packed cattle road, eager to spot a baby jaguar.

“We typically don’t travel this quickly,” our guide Raphael exclaims, his excitement palpable. “Hold on tight!” With hands clutching our caps, we zip across bridges and through the brush, capturing shaky videos as we catch our first glimpse of the 1.3 million-acre reserve. The first thing that catches my eye: cows. So many cows. An essential part of the Caiman Ecological Refuge is balancing livestock farming, ecotourism, and conservation. These jowly, chalk-white cows coexist with jaguars—the ranch loses about 1.5 to 2 percent of its herd each year, a significant cost to support the cat population. We know we’re nearing these agile predators (the third-largest big cats after tigers and lions) when we see dozens of cattle frozen on the roadside, heads all turned in one direction like spectators watching a brawl. Across the path and down by the watering hole, three capybaras squeak loudly as two jaguars swim nearby. Are the cats stalking their prey? Cooling off in the afternoon heat? Perhaps both?

Our guide believes these two jaguars we’ve been tracking—the mother and her cub, likely around four months old—aren’t on the hunt, as jaguars usually ambush their prey rather than casually paddle over to feast at the capybara buffet. Yet, there’s a tension in the air that has us holding our breaths as we watch nature unfold.

Photo by Laura Dannen Redman

Given my fondness for those adorable giant rodents, I’m relieved I don’t have to witness a jaguar take down a capybara. (I might be the only one in our group not eagerly anticipating the circle of life in action.) The mother and cub slip into the underbrush, and we follow slowly in the jeep, moving alongside the soft padding of their footsteps. Ever curious, the cub keeps popping its head out to glance at us before darting back into the trees. The mother, possibly hungry or simply exhausted from caring for her playful toddler, flops onto her back in the sun—a universal sign for: I need a nap. Undeterred, the cub leaps onto mom’s belly, initiating a playful tumble complete with gentle face swats and nuzzles that mirror the antics of parents and their young children. I find myself getting a bit emotional. After all, Mother’s Day is tomorrow, and my own kids, ages five and three, are likely playing rough 4,400 miles north of here.

Our guide Bruno proudly informs us that visitors have a 99 percent chance of spotting a cat on the reserve with OnçDinogoi. But the wildlife doesn’t stop there; you can also encounter tapirs, toucans, ostrich-like rheas, capuchin monkeys, blue-claw foxes, parakeets, snakes, and even spiders (yikes). Jabiru storks—the emblematic bird of the Pantanal—can be seen drinking from ponds in the early morning sun. Meanwhile, the region’s namesake caiman (a type of alligator) reveals itself at night, with glowing red eyes appearing by the hundreds, reminiscent of a zombie invasion.

Even better, visitors can engage in conservation initiatives, as we did with OnçDinogoi and Instituto Arara Azul, fostering a deeper connection to the area. I plan to return to the Pantanal with my family someday; I planted a tree for future macaws and need to see how it's thriving.

Essential Information Before You Go

Evaluation :

5/5