Guidelines for Planning a Respectful Indigenous Travel Experience

Recently, my friend Felix, a proud Chicagoan, visited Oklahoma for the first time. We took the opportunity to explore nearly every museum in Oklahoma City—the largest city I’ve ever called home. One of our final stops was the First Americans Museum (FAM), which we intentionally left for the end of our trip, knowing it would be a more poignant experience for me as an Indigenous person and native Oklahoman, compared to the American Pigeon Museum & Library.

Inaugurated in 2021, FAM is dedicated to narrating the shared histories of Oklahoma's 39 unique First American Nations. The museum was carefully curated, yet it proved to be an emotionally challenging visit. (Physically, it was tough too—I stumbled as I entered, scraping my knees and twisting my wrist. I thought it would have been more fitting to trip at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum, not here.)

As we navigated through the exhibits, which highlighted topics like Indigenous humor, historical stereotypes of “Indians,” and Native athletes in the Olympics, I felt tears welling up.

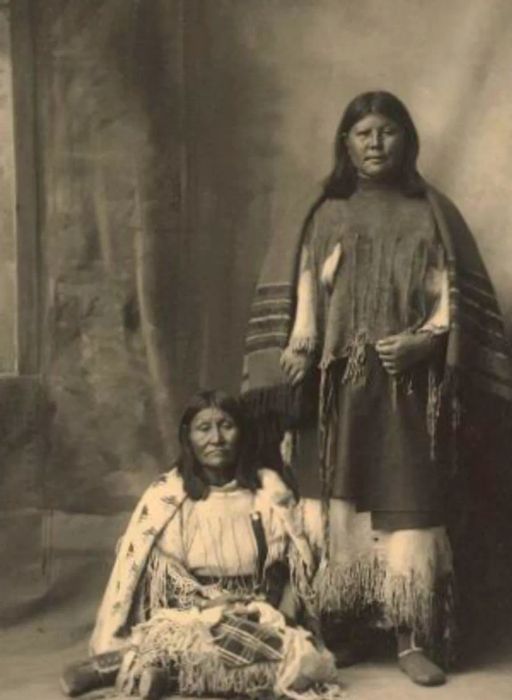

The exhibit that resonated with me the most was Winiko: Life of an Object, featuring artifacts on loan from the Smithsonian. These items were taken from Oklahoma’s tribal communities over a century ago. Although they were removed from their original contexts, to me, these objects still seemed to possess their spirits, almost as if they were alive.

Photo by Kit Leong/Shutterstock

Among the exhibits, I noticed dresses adorned with ribbons, embroidered stag designs, and intricate beaded jewelry. I recognized elements of my culture and those of the people I've met, worked alongside, and cherished. A map displayed my hometown, highlighting both Oklahoma and Indian Territory (a historical term referring to lands designated for the forced relocation of Native Americans), along with the Cherokee Nation Reservation. I reflected on my father, my Native parent, who passed away a few years ago, feeling somehow closer to him in death than I did in life. As a child, I viewed my identity as divided, split into two parts. I believed I would never fully grasp or embrace the Cherokee side of myself. Instead of lingering on that childhood perception, I directed my focus to elements I thought he would appreciate: the star maps, the creation stories, and the stickball sticks.

Later, Felix and I enjoyed lunch, sharing our favorite moments from the day. I confessed to him that discussing and writing about Native experiences remains challenging for me. While Native and Indigenous people share a collective identity, we are far from uniform. We represent diverse tribes and cultures, all of which have endured similar silences, forced and violent displacements from our ancestral lands, and a common neglect. Nonetheless, I hold onto the hope that people are inherently good. If we guide them on how to be more respectful and understanding, I believe they will make an effort.

I know I’m not alone in finding it difficult to discuss Indigenous issues. Despite my closeness to them, I often feel a gap in knowledge. To assist travelers in engaging with Native cultures respectfully and supporting Indigenous communities, I’ve compiled the following tips.

1) Recognize whose land you are visiting

Are you aware that 27 Indigenous tribes have historical ties to the land that encompasses and surrounds Yellowstone National Park?

Photo by Alex Person/Unsplash

Native peoples were forcefully removed from their lands, and many faced murder; they once regarded what are now U.S. national parks as their homelands and territories. Understanding whose land you are on is crucial. As Ojibwe author David Treur noted, "From a historical perspective, Yellowstone is a crime scene." (If you’re uncertain about the original inhabitants of a region, resources like Native Land Digital can help you learn more, whether you’re traveling or at home.)

The seemingly benevolent conservation efforts came with a heavy price: Theodore Roosevelt is often regarded as one of America's most cherished presidents and a proponent of the outdoors. During his presidency, he approved 150 national forests, 18 national monuments, five national parks, four national game preserves, and 51 bird "reservations" (using scare quotes as Treur suggests), all situated on or adjacent to Indigenous lands. In an 1886 speech, Roosevelt stated, "I don’t go so far as to think that the only good Indians are the dead Indians, but I believe nine out of every 10 are, and I shouldn’t inquire too closely into the case of the tenth." He regarded Native peoples as a troublesome obstacle to westward expansion.

Despite the park system's troubling history, significant changes are underway alongside the Land Back movement, which aims to return lands to their rightful stewards. The National Park Service has made substantial improvements to the information they provide about occupied lands, moving away from portraying parks as vast, untouched wilderness. Some parks are beginning to establish co-management agreements with local tribes. For instance, Acadia National Park is collaborating on a multi-year project with the Wabanaki Nations of Maine, allowing the community to once again harvest sweetgrass, a cool-season grass traditionally used for smudging and basket weaving, after nearly a century-long ban. Additionally, in Mount Rainier National Park, the Nisqually Tribe is researching three plant species that have long been harvested by the tribe, with their findings to be jointly presented with the park.

Before visiting a national park (or similar locations), it's essential to gather information about the land directly from the tribes whenever possible—tribal websites serve as excellent resources. Consider how native plants were ethically harvested and utilized for medicinal and ceremonial purposes. Recall that the land was meticulously cared for over centuries using methods such as controlled burns. Being aware of the past can enrich visitors' experiences today—and provide a more authentic understanding.

Courtesy of Boston Public Library/Unsplash

2) Explore Native history and culture during your travels

Often, the fear of overstepping boundaries or offending others can prevent us from truly engaging with different cultures and communities. While this concern is valid, I believe that as long as you approach interactions responsibly and prioritize listening over speaking, you will be on the right path. When you travel, make a conscious effort to seek out tribal museums or organizations connected to Indigenous communities.

For instance, my ancestral homelands include the Great Smoky Mountains (my tribe, along with many others, was forcibly relocated to Oklahoma along what is now known as the Trail of Tears), which stretch along the Tennessee–North Carolina border. Many visitors come to enjoy the charm of Gatlinburg or to embark on scenic hikes. However, they can also tour the Oconaluftee Indian Village, which aims to educate visitors about the fact that these mountains are still home to a vibrant community that advocates for the preservation of their sacred sites. Guests have the incredible opportunity to experience this living heritage. One of my favorite daily highlights is the variety of traditional dances that everyone is welcome to join—no need to worry about rhythm; even if you lack it like I do, you’ll still feel comfortable participating.

When visiting a cultural center or historical village, be sure to ask questions—this gives guides and historically marginalized community members a chance to share their stories and engage in the art of oral tradition. It also demonstrates your genuine interest and receptiveness to what is being shared.

Certain questions should be avoided, of course, such as How much Indian are you? or Can you tell me if I’m Native? However, these can be easily sidestepped and are not nearly as enjoyable to discuss.

3) Always seek permission first—then act

An essential trait of a respectful traveler is to follow the appropriate rules of conduct. This is especially crucial in locations that may have previously been, or may still be, sites of ceremonies, violence, birth, death, or other significant events. Generally, behavioral expectations will be communicated through signs, infographics, or a guide—so be sure to read and listen attentively.

Experienced travelers might feel they already possess some knowledge. However, it's important to remember that each Native community is distinct, with its own customs, rules, and governance. If anything is ever unclear, don't hesitate to ask. What might be acceptable elsewhere could be deeply disrespectful within an Indigenous context. For instance, in Hopi culture, taking photographs during ceremonies is considered highly disruptive. In my own tradition, I learned not to read aloud or speak certain words, as this might awaken something. A good guideline is: unless you receive an invitation, simply observe rather than participate.

Photo by Andrew James/Unsplash

Ultimately, travelers should embrace a sense of gratitude. They ought to appreciate the resilience and strength of Indigenous communities that have endured, flourished, and evolved despite numerous challenges. This appreciation is particularly crucial now, as we reflect on the pandemic, which led to a significant drop in Native tourism. During the lockdowns, tribal communities like the Navajo were especially hard hit by COVID-19 due to limited resources, infrastructure, and support.

As we re-enter the world, armed with greater knowledge and empathy, we recognize that travel can serve not only as a means to connect with these communities but also as a way to support and uplift them.

1

2

3

4

5

Evaluation :

5/5