I Celebrated Día de los Muertos in Oaxaca, Mexico — Here's How I Organized My Unforgettable Adventure

From left: A Día de los Muertos parade along Calle Macedonio Alcalá in Oaxaca, Mexico; a doorway in Oaxaca City beautifully decorated with marigolds, which are said to lure the spirits of the departed.

Photo: Daniel Seung Lee

From left: A Día de los Muertos parade along Calle Macedonio Alcalá in Oaxaca, Mexico; a doorway in Oaxaca City beautifully decorated with marigolds, which are said to lure the spirits of the departed.

Photo: Daniel Seung LeeI believe it was my grandmother, Moyra, who instilled my passion for travel. After losing her husband in her sixties, she utilized his pension to embark on a series of adventurous solo journeys. I still recall the photos: Moyra sailing on the Danube; Moyra standing before the Pyramids; Moyra in Tiananmen Square, looking as stylish as ever in her panama hat.

My grandmother reached the age of 103, yet she never had the chance to visit Mexico. Nearly a decade after her passing, I received an invitation to Oaxaca for Día de los Muertos, or the Day of the Dead. I could almost hear her exclaiming, “Darling, how wonderful.” The event organizers encouraged me to bring a photo of a loved one to honor at the festival. So, I retrieved Moyra’s picture, tucked it in my carry-on, and off we went together.

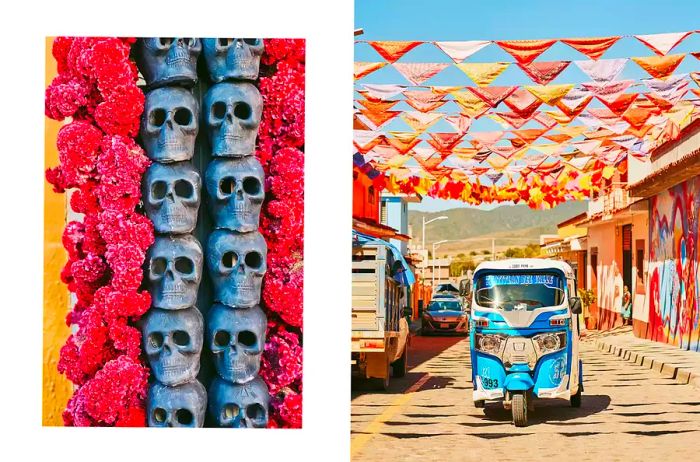

From left: Día de los Muertos adornments brightening the streets of Oaxaca City; festive banners lining a street in Teotitlán del Valle, a community of artisans just outside Oaxaca.

Photo: Daniel Seung Lee

From left: Día de los Muertos adornments brightening the streets of Oaxaca City; festive banners lining a street in Teotitlán del Valle, a community of artisans just outside Oaxaca.

Photo: Daniel Seung LeeDía de los Muertos, as fans of the Disney film Coco will know, is one of the most culturally significant and visually stunning celebrations in Latin America, with Oaxaca City in southern Mexico often regarded as its heart. During late October and early November, the cobblestone streets come alive with colorful parades, cemeteries shimmer with candlelight, and each home sets up an ofrenda, or altar, to honor those who have departed.

I was participating in a group trip organized by Prior, a travel company that, since its inception in 2018, has built a reputation for crafting experiences that blend authenticity with an aesthetically pleasing, Instagram-ready flair. (Its impressive roster of celebrity clients certainly adds to its appeal.) A new series of itineraries, launched in partnership with Capital One, focuses on festivals, with Día de los Muertos as the inaugural event.

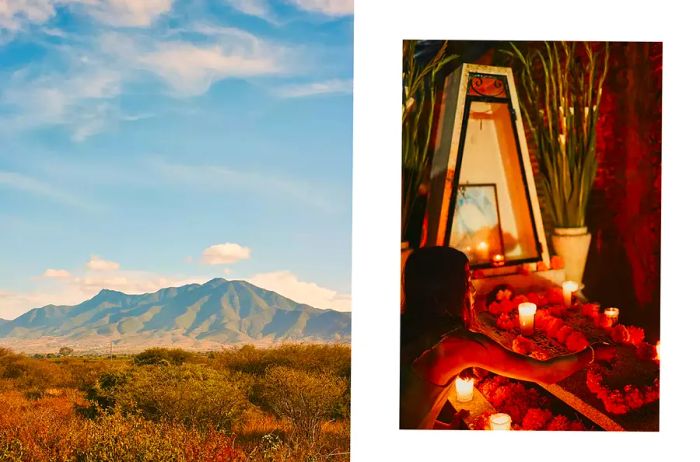

From left: A scenic view of the hills surrounding Oaxaca City; a grave in Xochimilco cemetery during Día de los Muertos.

Photo: Daniel Seung Lee

From left: A scenic view of the hills surrounding Oaxaca City; a grave in Xochimilco cemetery during Día de los Muertos.

Photo: Daniel Seung LeeOur accommodation was Escondido Oaxaca, a historic mansion in the Centro Histórico that was transformed into a boutique hotel by Grupo Habita in 2019 — now synonymous with stylish, modern stays in Mexico and beyond. As I stepped through the hotel’s grand wooden doors, I entered a courtyard brimming with marigolds, believed to draw the souls of the deceased with their fragrant scent and vibrant blooms. Inside my room, atop a bed that appeared to float over a concrete floor, was a small dish containing two dark-chocolate skulls infused with mandarin and marigold from FlorCacao, a local artisanal chocolatier.

About an hour later, my group — primarily composed of writers and photographers for this preview trip — convened for cocktails on Escondido’s rooftop. I toasted with a mezcal margarita alongside David Prior, who founded the company after beginning his career in food and publishing. He shared insights about the concept behind this new series, which will take other groups to Paris for Bastille Day and Seville, Spain, for the Feria de Jerez festival. “These events showcase culture at its most emblematic,” he noted. However, curating the right itinerary can be challenging, particularly for occasions like Día de los Muertos, where non-Hispanic individuals in skull makeup face accusations of cultural appropriation. As Prior aptly asked, “How do you capture the essence while ensuring it feels authentic and magical?”

From left: A massive mannequin featured in a Día de los Muertos parade; the cathedral of Oaxaca City.

Photo: Daniel Seung Lee

From left: A massive mannequin featured in a Día de los Muertos parade; the cathedral of Oaxaca City.

Photo: Daniel Seung LeeAs if on cue, we heard music drifting up from the courtyard. A lively group of musicians and dancers had arrived, beckoning us down from the rooftop and out into the street. Caught in their whirlwind of color, movement, and sound, we reached an intersection bustling with a crowd. Beyond it, a sea of thousands surged forward. The parade featured fireworks, drummers, and multiple brass bands. There were stilt-walkers and women balancing three-foot floral displays atop their heads. Some donned vibrant, rainbow-colored costumes, while others wore black and white. Many faces were painted to resemble La Calavera Catrina, the iconic skeleton figure symbolizing the festival. Above, pink and orange banners danced against the dark night sky. It was a scene both joyful and haunting, utterly unique to this place and time. Día de los Muertos had begun.

The Day of the Dead dates back around 3,000 years to the Aztecs, who created a ritual honoring Mictecacihuatl, the goddess of the underworld. When the Spanish arrived in the 16th century, this event blended with the solemn Catholic traditions of All Saints’ Day and All Souls’ Day; five centuries later, Día de los Muertos has forged its own distinct identity — so much so that it was recognized by UNESCO as an Intangible Cultural Heritage in 2008.

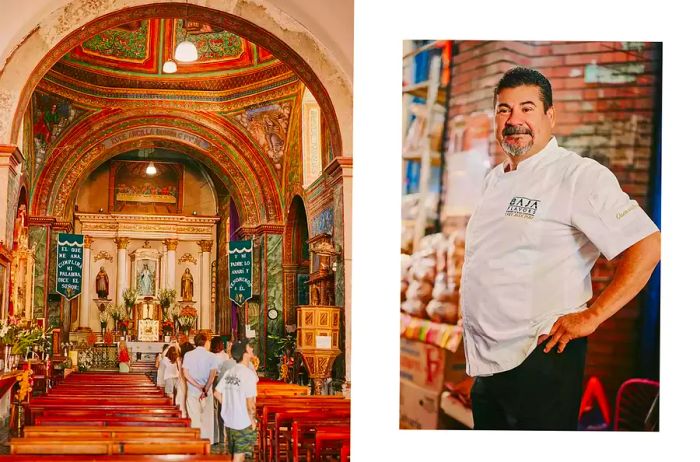

From left: Inside the Iglesia Preciosa Sangre de Cristo in Teotitlán del Valle; Chef Alejandro Ruiz at Portozuelo and Casa Oaxaca El Restaurante.

Photo: Daniel Seung Lee

From left: Inside the Iglesia Preciosa Sangre de Cristo in Teotitlán del Valle; Chef Alejandro Ruiz at Portozuelo and Casa Oaxaca El Restaurante.

Photo: Daniel Seung LeeTo better understand its significance, we ventured the next morning to Teotitlán del Valle, approximately 45 minutes from the city. This rural community, home to Indigenous Zapotec weavers and dyers, is also the birthplace of our guide, Edgar Mendoza Martinez. After a brief tour of Teotitlán’s market and central square, he led us into his family’s red-roofed compound. In a central courtyard, where roosters pecked beneath a pomegranate tree and six-foot lengths of sugarcane leaned against the wall, we met Edgar’s cousin, affectionately known as Tia Micaelina.

A petite woman wearing a traditional braided headband and apron, Micaelina welcomed us into a room adorned with a large ofrenda for the holiday. In front of a wall lined with gold-framed Catholic icons, the smoke of copal incense curled gracefully through beams of sunlight. Micaelina highlighted photos of her parents, along with miniature loaves of bread and pieces of chocolate artfully arranged on a table beneath the shrine, intended to entice the souls of los angelitos, or deceased children. I inquired of Edgar if any angelitos had passed from this family. “Yes,” he replied. “Her little sister was lost.”

I thought about my photo of Moyra — which, regrettably, I had left behind at the hotel. “You’ll know when you find the right ofrenda to place it on,” Edgar had told me on the first day. Clearly, this wasn’t the one.

Fireworks erupting over Templo de Santo Domingo de Guzmán, viewed from Cobarde restaurant in Oaxaca City.

Photo: Daniel Seung Lee

Fireworks erupting over Templo de Santo Domingo de Guzmán, viewed from Cobarde restaurant in Oaxaca City.

Photo: Daniel Seung LeeCraftsmanship is a key focus on Prior trips, and Oaxaca’s vibrant artisan traditions, ranging from basket weaving and woodcarving to embroidery and pottery, make it an ideal destination for visitors to explore and acquire the charming decorative items that Oaxacan artisans have created for centuries.

In Zapotec communities like Teotitlán del Valle, entire families — often whole towns — typically dedicate themselves to a single craft. For generations, Edgar shared, his family had been weavers. By becoming a tour guide, he was one of the first to break away from this tradition. “I realized that if I wanted to understand the world, I had to escape from that,” he explained.

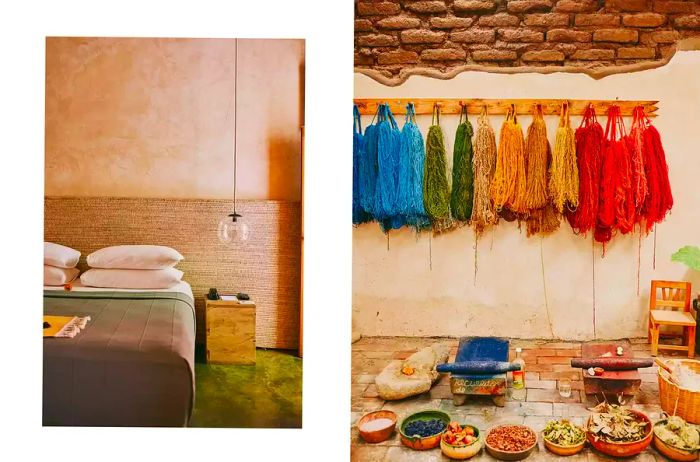

Others in Teotitlán del Valle have managed to preserve their family’s craft while also looking outward and toward the future. In a nearby compound, we met Alejandro Mendoza and Verónica Bautista, a married couple who operate Casa Don Taurino. This dyeing and weaving workshop was established by Mendoza’s grandfather, and under the couple’s leadership, it has recently focused on revitalizing the ancient practice of using organic pigments.

From left: Elegant place settings for a private dinner at a hacienda; a group of chinas oaxaqueñas dancers welcoming Prior guests outside Escondido Oaxaca.

Photo: Daniel Seung Lee

From left: Elegant place settings for a private dinner at a hacienda; a group of chinas oaxaqueñas dancers welcoming Prior guests outside Escondido Oaxaca.

Photo: Daniel Seung Lee“Natural dyes were being replaced by synthetic pigments,” Mendoza explained. “This tradition was fading away.” He gestured to wooden bowls filled with ingredients arranged on the floor: dried pomegranate skins for a mustard-colored dye; marigold petals for yellow; tree moss for beige; and leaves from the Indigofera plant for indigo.

One bowl contained a silvery, grainy substance: la grana cochinilla, or cochineal, an insect that resides on the prickly-pear cactus. When cooked and crushed, these insects produce a deep scarlet dye. When the Spanish arrived in Oaxaca, Mendoza noted, they were astonished to discover that these unexpected bugs yielded a richer red than they could produce back home, leading to shipments of the dye to Europe. At one point, he remarked, “it was nearly as valuable as gold.”

Bautista began to crush a handful of cochinilla with a rolling pin, revealing a vibrant scarlet hue. We applied the dye to our palms, observing the subtle variations in shades influenced by our unique skin chemistry. Next, we immersed squares of cotton fabric in a vat of indigo dye, creating striking tie-dyed patterns in a deep, resonant blue. Finally, we met a young designer, Angélica Torres Ospina, who operates a workshop next door, crafting stylish cotton and linen garments, all dyed using her neighbors’ natural pigments.

In other parts of Teotitlán, artisans have showcased their crafts on a global scale. A few streets away from Casa Don Taurino, we visited Casa Viviana, the studio of 76-year-old candlemaker Viviana Alávez, who has amassed 24,000 followers on Instagram and has even been featured in Vogue.

The elegant, silver-haired Alávez and her daughter-in-law, Petra Mendoza, create traditional velas — Oaxacan candles adorned with wax embellishments around their bases. By reimagining their velas as imaginative sculptures, the duo has earned a reputation as the undisputed masters of this craft. Even the simplest candles come in a dazzling range of colors and are decorated with flowers, shells, or skulls; some centerpiece pieces, custom-designed for weddings and festivals like Día de los Muertos, can reach six feet in height and take up to two months to complete.

From left: Sleek and minimalist décor at the hotel Escondido Oaxaca; crafting natural dyes at Casa Don Taurino.

Photo: Daniel Seung Lee

From left: Sleek and minimalist décor at the hotel Escondido Oaxaca; crafting natural dyes at Casa Don Taurino.

Photo: Daniel Seung LeeWhile the women utilize techniques that have remained unchanged for generations — beeswax from Chiapas dyed with natural pigments like cochineal and shaped by hand or with wooden tools — they are celebrated for their striking designs, often featuring floral patterns inspired by the surrounding landscape. Some credit Alávez with single-handedly preserving this tradition.

It felt somewhat regal when Alávez invited me to sit on the earthen floor of her workshop at the base of her wooden stool and attempt to create a fuchsia wax rosette. The outcome wasn’t entirely embarrassing, but it paled in comparison to the exquisite pieces available at Casa Viviana. My group spent the next hour choosing which candles to purchase, then patiently waiting as Alávez’s family members carefully wrapped each one. (One fantastic service offered on Prior’s trips with Capital One is that your purchases are shipped home directly from your hotel room.)

Food is another major focus for Prior, and in Oaxaca, you don’t have to search hard to find meals that broaden your understanding of Mexican cuisine, whether served on a vinyl or white linen tablecloth. In Teotitlán del Valle, we watched as women prepared tortillas and quesadillas over an open flame, savoring them hot from the stove with a zesty avocado salsa. At La Cocina de Humo, a restaurant in Oaxaca City, we dined at a long, candlelit table while chef Thalía Barrios and her team recreated the rich, smoky flavors of the Sierra Sur region, cooking everything over a wood-burning stove and presenting it on stylish earthenware from local artisans.

However, our most unforgettable meal was the one we prepared ourselves. Early on our second morning, we ventured to the Mercado Central de Abastos with chef Alejandro Ruiz, whose Casa Oaxaca El Restaurante is renowned for introducing the region’s cuisine to a global audience. “Everything begins at the market,” Ruiz remarked. “I’ve been shopping here since childhood — for over forty years.”

Like a guiding light in his chef’s whites, Ruiz navigated us through the market’s winding alleys, pausing occasionally to chat with stallholders or snap selfies with admirers. Fresh produce overflowed at every stall, accompanied by a vibrant array of Día de los Muertos decorations: sugar skulls, papier-mâché skeletons, towering displays of marigolds, and colorful cut-out paper flags known as papel picado.

While our group frequently halted to capture photos and pick up souvenirs, Ruiz remained focused, selecting a whole chicken with bright yellow feet still intact; a hefty, round squash; tomatoes and tomatillos; avocado leaves; thyme and oregano. At one stand, we examined a variety of dried chiles displayed in open sacks. Ruiz grabbed a bag of the largest variety, chilhuacle rojo, to incorporate into the mole we’d be preparing that afternoon. “This one has smoky, umami, and mineral notes,” he explained.

A candle-making demonstration at Casa Viviana in Teotitlán del Valle.

Photo: Daniel Seung Lee

A candle-making demonstration at Casa Viviana in Teotitlán del Valle.

Photo: Daniel Seung LeeWith our bags filled to the brim, we made our way to Portozuelo, the picturesque farm just outside Oaxaca City where Ruiz grew up and formed a deep bond with the land and its bounty. Today, the farm boasts a restaurant and event space where everything is prepared in the traditional Oaxacan style: over an open wood fire, using ingredients sourced from the local market or cultivated on-site.

Portozuelo employs around 35 locals as cooks and servers, and a few welcomed us with trays of ice-cold beers and mezcal cocktails upon our arrival at the kitchen-dining area, a tile-roofed space open to the air on all sides. Ruiz organized the group into teams: mine was tasked with creating mole, the notoriously intricate sauce that required 28 ingredients for this version. Luckily, my teammates were kitchen aficionados; one, a published cookbook author, quickly took charge of the grill to char plantains, tomatoes, onions, spices, and herbs.

However, it wasn’t until mid-afternoon that we finally sat down for lunch at a long wooden table, sharing generous bowls of richly flavorful traditional mole, alongside a green version with chicken, and for dessert, fresh pan de muertos— delicate buns sprinkled with sesame seeds, each featuring a tiny carita, or sugar face.

Our final night coincided with the first of the two primary nights of the Día de los Muertos festivities, and anticipation filled the air as we gathered at Cobarde Oaxaca, a restaurant with views overlooking the city’s zocalo, or main square. From our table on the second-floor terrace, we observed passersby capturing photos of street performers in intricate costumes below. Their backdrop was the illuminated façade of the Templo de Santo Domingo de Guzmán — which was delightfully framed by fireworks for a few enchanting moments.

From left: Designer Angélica Torres Ospina, who dyes her garments using organic pigments made at Casa Don Taurino; the hacienda setting for a private dinner organized by the travel company Prior.

Photo: Daniel Seung Lee

From left: Designer Angélica Torres Ospina, who dyes her garments using organic pigments made at Casa Don Taurino; the hacienda setting for a private dinner organized by the travel company Prior.

Photo: Daniel Seung LeeAfter savoring four incredible courses, we were enjoying our smoked tres leches cake when Edgar received a call from a contact, who informed him that strong winds were extinguishing all the candles at the main cemetery. Instead, Edgar decided we would head to Xochimilco, a smaller burial ground in a residential area. As we passed through the gates under a silvery half-moon, clouds drifted by, leading us to the edge of the cemetery, where a group of women and girls gathered around a grave illuminated by votive candles. They explained they were there to honor Maria, the family matriarch.

Two of Maria’s young granddaughters, their faces painted like skulls, tended to the flickering candles. Maria’s daughters, adorned with marigold headdresses, circulated shots of mezcal in small plastic cups while singing “Amor Eterno,” a cherished funeral song by Mexican artist Juan Gabriel. We noticed similar family gatherings at other graves; some were filled with festive energy, while others, perhaps more recently dug, carried a somber atmosphere.

As we exited the cemetery, I inquired about Edgar’s plans for the remainder of the celebration. He shared that he would return to Teotitlán del Valle the following day to honor his father, who had passed away a decade earlier. Discussing his father with visitors stirred up complex emotions for him. “He always dreamed of being a tour guide,” Edgar reflected. “I used to feel guilty, but I realized that the best way to honor him was to pursue this work.”

An ofrenda set up at the family home of Prior guide Edgar Mendoza in Teotitlán del Valle.

Photo: Daniel Seung Lee

An ofrenda set up at the family home of Prior guide Edgar Mendoza in Teotitlán del Valle.

Photo: Daniel Seung LeeAs my time in Oaxaca was drawing to a close, I still hadn’t located the perfect ofrenda for my grandmother’s photo. Venturing into the Centro Histórico for a coffee before my flight the next morning, I stumbled upon Casa Oaxaca, Alejandro Ruiz’s hotel and restaurant. Inside, I discovered a serene courtyard where guests enjoyed their coffee and a relaxed late breakfast, along with a prominent ofrenda adorned with pictures of the chef’s loved ones in beautifully crafted silver frames.

Surrounded by an abundance of candles, fruits, nuts, flowers, sugar skulls, and bottles of Corona, I placed my photo of Moyra, beaming happily. Though she preferred red wine over beer, I knew she would have adored this vibrant place—its warmth, its colors, and its celebratory spirit. What an adventure! I could almost hear her say as I stepped out into the sunlit street.

Four-day Día de los Muertos experiences with Prior and Capital One starting at $2,400 per person.

A version of this article originally appeared in the March 2024 issue of Dinogo under the title "Good Spirits."

1

2

3

4

5

Evaluation :

5/5