I Traveled 600 Miles Across Japan in Search of Pizza Toast

The pizza toast felt like a sacred ritual, a comforting presence as I found solace in it during my emotional moments. It delivered everything I had hoped for at that exact moment.

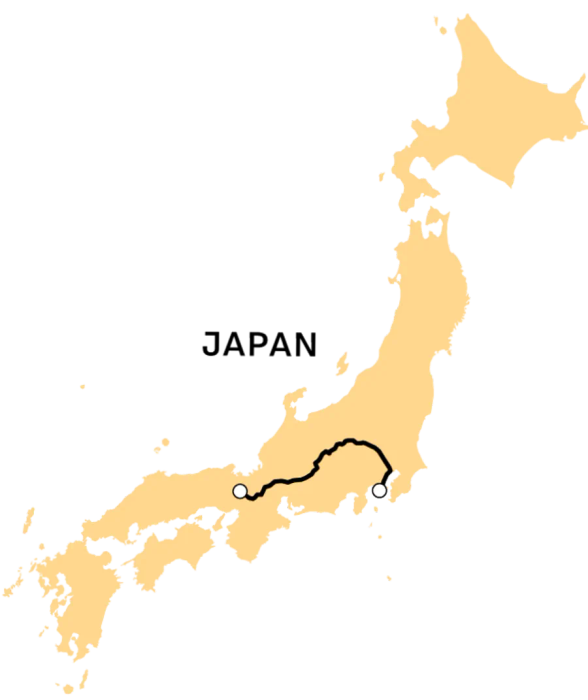

Picture this: I was in the midst of an epic journey across Japan, tracing the historic Nakasendō route, and ultimately walking over 1,000 kilometers (about 621 miles). On this particular day, I was battling an eight-hour stretch of blistering pavement, which I had dubbed “Pachinko Road.” The Nakasendō links Tokyo and Kyoto, meandering through forests, quaint villages, and sprawling suburbs. I found the urban sprawl intriguing, its endless big-box stores representing a unique segment of the world. But on Pachinko Road, there was a distinct Japanese flair: convenience stores, tonkatsu chains with piglet mascots, ubiquitous udon noodle and curry spots, and pachinko parlors—those noisy, smoke-filled gambling dens with warning signs cautioning parents not to leave their infants in cars as they become mesmerized by the clinking metal balls. I had been traversing this stretch of Japanese roadway for two days, a zone where parents inadvertently exposed their children to extreme heat.

Then, as that monotonous stretch faded, I began to see homes, small gardens, and signs of human touch. Just outside of Gifu city, I noticed a sign with a modern design that read “Yashiro” in Japanese. As I approached, observing the gently curved windows and the dainty frosted-glass orb above the door, I felt confident that they would have the pizza toast I was craving.

An abandoned karaoke bar on “Pachinko Road”

An abandoned karaoke bar on “Pachinko Road”When I first arrived in Japan as a 19-year-old undergraduate, I could barely stomach any of the local cuisine. Sushi, soba, natto (fermented soybeans typically eaten for breakfast), and eel were inconceivable to me. Even ramen wasn’t my favorite. I was used to fried bologna, Spaghetti-Os, Fruit Roll-Ups, and Twix. The intricate flavors and textures of Japanese food were lost on my taste buds. Instead, I found refuge in a quaint, traditional Japanese café—a kissaten—near my university in Tokyo. There, I discovered “pizza toast.” The name caught my interest, and the dish seemed like something suitable for a child. It became a comforting link between my past and present. Back then, I didn’t think much of it; it was just a dependable meal, and the kissaten itself served as a comforting haven where I could enjoy black coffee, smoke, and read novels.

Years later, to deepen my connection with Japan, I started embarking on various exploratory walks across the country. I followed the routes of ancient Japanese haiku poets in the north and documented pilgrimage trails in central Japan. I engaged in rituals with mountain ascetics and traversed their hidden mountain paths. Fluent in the language, I easily conversed with locals and discovered that combining language skills, solo walking, and interacting with strangers provided a unique insight into the minds and lives of the Japanese people.

The writer’s journey spanned over 620 miles across Japan, following the historic Nakasendō route

The writer’s journey spanned over 620 miles across Japan, following the historic Nakasendō routeSeveral months ago, as I planned my trek along the Nakasendō, I sought a guiding theme for my adventure. Before setting off, I devised a plan to savor as many varieties of my trusted pizza toast as possible while tracing its origins to the traditional Japanese kissaten, the one place where this treat is reliably found.

Kissa, as they are endearingly known, are like relics frozen in a specific historical moment. Japan follows a unique era-based calendar, having recently transitioned to Reiwa in May with Emperor Akihito’s abdication. Before Reiwa was Heisei, and before Heisei was Showa. Kissa are deeply tied to Showa, which spanned from 1926 to 1989 and is often regarded as Japan’s “golden age.” This era is marked by its vibrant colors, industrious spirit, and nostalgic focus on postwar recovery. Showa encompasses the narrow alley bars of Tokyo’s Golden Gai, old-fashioned barber shops nestled among modern skyscrapers, and, above all, the kissa.

I anticipated that kissa, like barbershops, would be plentiful on my journey, many serving pizza toast. These kissa would link the diverse landscapes I traversed, with pizza toast representing a key element of my Japanese experience.

However, I soon learned from kissa expert and author of Nagoya Kissaten Toshiyuki Otake, during our coffee and toast chat, that the peak of Japanese kissa occurred around Showa 56 (1981). At that time, there were about 150,000 kissa across Japan. Otake remarked with a smile, “It was probably too many.” Three years ago, the number fell below 70,000, and the decline continues sharply. Many remaining shop owners are elderly, and their children are not taking over, suggesting that traditional kissa may soon vanish.

A glimpse into the typical setting of Mami kissa

A glimpse into the typical setting of Mami kissaPizza toast is exactly as you picture it: transforming a slice of toast into a pizza-like creation. Imagine a thick piece of white bread topped with tomato sauce, cheese, and perhaps some onions and green peppers. After that, it’s up to the chef’s discretion. It’s like a warm embrace from a toaster oven.

This dish is a bit of an enigma—something Japanese people seldom consider and that visitors often regard with a puzzled look. It’s a comfort food firmly rooted in the postwar culinary landscape, sitting alongside such curiosities as Spam in Okinawan cuisine and ‘Neapolitan-style’ spaghetti made with ketchup. It’s a simple pleasure that extracts joy from minimal ingredients and preparation, rising above economic constraints.

The most remarkable pizza toast I encountered on my journey appeared on the very first day, just a few kilometers from my starting point in Kamakura. The kissa was located in Ofuna, where I stopped for a break on my way to Yokohama. The owner of Bugen, Akira Yamane, was a quietly kind man with gentle eyes, who had been perfecting his pizza toast for 42 years. His creation was a true marvel of toast craftsmanship.

Typically, pizza toast is made on slices of white bread about an inch and a half thick. Yamane’s unique approach involves cutting the bread into long thirds and then scoring it lightly on the bottom into shallow thirds. He removes most of the crust, leaving just a small edge. The prepared bread is then topped with a delicate, sweet tomato sauce, mozzarella, green peppers, onions, mushrooms, and thinly sliced salami.

From a customer experience viewpoint, a gentle pull on any of the toast strips yields a square, perfectly bite-sized piece of pizza-like bliss. And the crust? “I noticed some customers don’t enjoy eating the crust,” Yamane mentioned, “So I made it easy to remove. But for those who do enjoy the crust, cutting it allows for a bit of extra char.”

The pizza toast at Yashiro — a delightful find on the edge of “Pachinko Road” — was just what I anticipated: locally baked bread as white as can be, generously spread with ketchup, topped with ultra-thin tomato slices, raw onions, green peppers, American cheese, a touch of cured ham, and small salami slices.

Yashiro’s ambiance was quintessential kissa: The tables were low, glass-topped squares for groups of four, with the menu displayed underneath the glass, reminiscent of a Greek diner in Hartford, Connecticut. The seating consisted of what appeared to be tiny sofas, known as “sofa chairs” or sofa isu, a transitional furniture that Japan never fully moved past. Traditionally, Japanese people sat cross-legged on zabuton cushions or more formally in seiza style on bent knees. The sofa isu offers a middle ground between the seiza posture and a regular chair. As Japan approached the 20th century, it began inching towards the Western style of chair-and-table dining, and the kissa represented a blend of traditional tea house and Chicago diner.

Yashiro’s iconic pizza toast

Yashiro’s iconic pizza toast Yashiro

YashiroKissa stand in stark contrast to Pachinko Road: they are intimate and unique. However, their design aesthetics are similar, making them feel like wandering homes, offering a sense of familiarity no matter which one you visit.

The owner of Yashiro was 73 years old and was assisted by his wife and daughter. It was a family-run business, like many others. Yet, among all the kissa I explored, this was the only one with a second-generation participant. Most owners view their kissa as a personal endeavor rather than a legacy. “If given a different choice, I would have taken it,” many told me, not out of regret, but as a straightforward observation.

Japan’s population is declining. The birth rate isn't high enough to maintain the current figures, which peaked at around 127 million in 2008. While the bustling cities of Tokyo, Osaka, and Kyoto might mask the demographic shift, the aging population is starkly evident in the rural areas.

Japan's main shopping streets are lined with stores guarded by heavy metal shutters when closed. Towns that were once bustling 10 or 20 years ago are now referred to as “shutter towns.” I’ve wandered through many of these places where store owners have passed away, leaving their shops shuttered and abandoned, never to reopen.

In shutter towns, the younger generation naturally migrates to cities in search of better opportunities. These towns turn into ghost towns. Echoes of the past remain: faded posters of beauty models in neglected drugstore windows, and the ghostly outlines of old signs above defunct hardware stores.

However, as I left Yashiro and ventured into the Gifu City area, I noticed fewer shutters down on weekday afternoons, and kissa seemed to thrive like bioluminescent plankton on a summer night beach. Everywhere I turned, there was another kissa, glowing softly with inviting lights and quirky signs. The population density hadn’t changed; I was still in a suburban area, but it felt like I had crossed an invisible boundary of kissa culture. So when I saw the elegantly designed indigo-dyed noren at Minato Coffee, I couldn’t resist popping in to check it out.

Minato Coffee is set in a renovated minka, a traditional Japanese farmhouse characterized by limited natural light, lofty ceilings, and rugged wooden beams. The café offers half of its seating with standard tables and chairs, while the other half is a tatami area with cushions and low tables. I chose a Western-style chair and ordered the “morning service” set — coffee accompanied by free toast and eggs. Strangely, pizza toast was missing from the menu. The meal was straightforward: thick slices of buttered white bread, jam on the side, and a hard-boiled egg.

Despite it being just 9 a.m., the café was unusually busy, not with the usual crowd of elderly, retired, chain-smoking men, but with young people who looked like Japanese tourists. There was a noticeable amount of Instagramming happening.

Eventually, a small elderly man shuffled in and took a seat beside me. He placed a ticket on the table and unfolded his newspaper. The waitress approached, quietly swapped the ticket for a black coffee, a hard-boiled egg, a small salad, and some toast.

The ticket system is a hallmark of kissa culture. You purchase a booklet of tickets — typically 11 for the price of 10. Each ticket entitles you to a coffee, and in the morning, a “morning set,” which is what the elderly man seemed to have ordered. Some kissa keep these booklets on the wall for each regular, akin to how izakaya patrons might store a bottle of their preferred whisky with their name on it behind the bar. At Minato, everyone was young and lively. When I inquired about the owner, I discovered that Minato Coffee is managed by a rare kissa figure: a young woman. In all my travels, I encountered only two female-run kissa, and none were as young as Inoue Manami, Minato's founder.

Owner Inoue Manami outside Minato Coffee, one of the few traditional kissa operated by a woman

Owner Inoue Manami outside Minato Coffee, one of the few traditional kissa operated by a womanShe established the café two years ago after apprenticing at a more traditional kissa. Her goal was to preserve the “morning service” tradition, which she said originated in Ichinomiya — a small industrial town between Gifu and Nagoya. She acknowledged, however, that no one under 50 buys the coffee tickets anymore. “Older patrons are accustomed to kissa culture,” she noted. “Younger patrons lean towards convenience store culture.”

Inoue mentioned that Instagram significantly boosted her business. The term Insta-bae refers to something that looks great on Instagram. Young food enthusiasts travel from afar to sample her highly Instagrammable dango — rice dumplings — arranged in threes on wooden sticks, spread out like a deck of cards on a round plate. It's her unique take on what you might find at a kissa.

She eagerly showed me around the 105-year-old building, which was officially recognized as a cultural property in 2017. “We barely altered anything when we took over,” she said, gesturing to the grandfather clocks, an old wooden chest in the back, and the cracked glass of the engawa hallway overlooking a small garden. The building was once a paper mill, then a soba shop, and now it occupies a space between a traditional kissa and a modern café.

I inquired about pizza toast and wondered if there might be a shop along the way that invented it. Was there a place that first served this toast variation? She didn’t know, but speculated that if such a place existed, it would likely be in Ichinomiya or Nagoya. If I wanted to trace the origins of kissa, those would be the places to visit, just a bit south of where we were.

Inoue and her team escorted me out, bowing as I returned the gesture. Even half a kilometer down the road, they continued to bow as I crossed the Nagara River against a strong headwind, heading into the expansive, rice paddy-filled plains of Gifu.

Can a city smell like toast? I’m not saying Nagoya smelled entirely of it, but I was convinced I detected the aroma of toast even in the subway, on the commuter train connecting Nagoya to Ichinomiya, and while walking around with no clear source of baking in sight. It felt as though toast had permeated either the city or my senses.

Nagoya is a vibrant, bustling port city with no signs of abandonment. It's alive with people, many of them young. As a crucial Shinkansen hub between Tokyo and Kyoto, it will soon become even more central when the maglev train connects it to Shinagawa in just 40 minutes starting in 2027.

In contrast, Ichinomiya, located just 10 kilometers north of Nagoya, exudes a sleepy charm. It epitomizes the shutter town archetype. On a Sunday afternoon at 2 p.m., I spotted only four people on the main street.

I ventured to Ichinomiya without a guide, relying solely on Inoue Manami's assurance that this was the heart of morning culture. She promised that if I sought kissa heaven, this was the place to find it.

My initial stop in Ichinomiya was Kissa Oedo. Though it had only recently opened and lacked the classic kissa elements, I decided to check it out. The 20-minute walk from the station was so desolate that I feared nothing would be open, so I was grateful for anything available. The emptiness of the area was marked by Oedo's flashing red light, a beacon of life, food, and sustenance in a barren landscape.

An empty street in Ichinomiya

An empty street in IchinomiyaThe pizza toast came with French press coffee, which was the best I had tasted at any kissa. The toast itself was remarkably straightforward: airy white bread topped with tomato sauce, mozzarella cheese, and corn. It was like savoring a light, umami-rich cloud that settled gently in the stomach. The place had a welcoming atmosphere, and the regulars seemed amused by my presence; elderly women exchanged curious glances and giggles in my direction. Two penguin statues guarded the entrance.

When I shared my search for pizza toast and beyond with Ito Tsuyoshi, the owner, he disappeared into the back and returned with the slim Ichinomiya Official Morning Guide.

Released in 2018, this guide, created by the city, organizes its 96 — yes, 96! — recommended kissa into various categories. It classifies these spots by their ‘vibe,’ ranging from retro and fancy to karaoke-themed, texture-rich, modern, or homey.

Specialty genres are divided into 18 categories, including omelets, waffles, and sandwiches. Toast is further broken down into three subcategories: simple toast, French toast, and ‘toast with toppings.’ The guide also features breakfast treasures like the Ichinomiya City Hotel’s offering of an all-you-can-eat hard-boiled egg basket with waffles and coffee for 600 yen. If you’re ever in the mood for a bounty of eggs, this is your destination.

Simply holding the guide seemed to unveil the hidden essence of Ichinomiya’s kissa scene. As I roamed the town, they began to materialize between shuttered storefronts and overgrown, neglected lots, emerging like elements from a magic eye image. I chose my next destination based on its intriguing name: Canadian Coffee House. It was peculiar enough to pique my interest, and upon seeing the building, my pace quickened. This place felt significant, as though it held a key role. I couldn’t quite pinpoint why, but Canadian Coffee House seemed to elevate the status of all kissa.

The shop’s design resembled an overturned canoe, standing two stories high but lacking a second floor, so the interior soared straight up to its rounded peak. Constructed entirely from Canadian red cedar, it felt like being inside a whiskey barrel or a shipwrecked hull. I perched on one of the hefty cedar stools — there were about twelve, each weighing at least 50 pounds. Mr. Sakai, the proprietor, wore a shirtsleeve, vest, and a gray polka-dot tie, with his thinning hair slicked back with pomade. His long, angular face was quick to light up with a smile, showcasing his silver dental work. Pizza toast wasn’t on offer, so I opted for the standard morning set. He soon returned from the kitchen with a couple of thin slices of toast and a plate of peanuts alongside black coffee. One half of the toast was slathered in butter, while the other was topped with red bean paste.

On the bar in front of me, there was a small sign that read:

THE THREE ‘TINY HEART’ PRINCIPLES OF THIS ESTABLISHMENT

- Delicious water

- Natural ingredients

- Well-scented hand towels — infused with jasmine

View from behind the bar at Canadian Coffee House

View from behind the bar at Canadian Coffee HouseSakai was eager to chat. “Water,” he started, “is crucial for health.” His passion for water was reminiscent of General Jack D. Ripper from *Dr. Strangelove*. “My water is exceptional.” At 78 years old, Sakai is an avid ballroom dancer. He explained that ballroom dancing was the only sport he could practice year-round. “Posture is vital for health,” he continued. “I learned this through Zen meditation. Proper posture prevents internal organs from being compressed.” His eyes were clear and unblinking, conveying a mix of tenderness and melancholy. “Good posture and quality water. With those, people can live long and well.”

The building’s design wasn’t incidental; it was purposefully linked to air quality. Sakai previously operated his kissa in a building with low ceilings, where cigarette smoke drove him to distraction. So, he demolished his own house and constructed this cedar haven, featuring a double-high ceiling to keep smoke out of his lungs. After 40 years of operation, the place smelled delightful, free of the typical ashtray odor found in many kissa.

But why the Canadian touch? Why Canadian red cedar? Shortly after their marriage, Sakai and his wife planned a grand world tour, but his mother’s broken leg forced him to stay behind. “Go,” he urged his wife. “Travel the world.” She ventured alone, exploring Europe and the Americas in the early ’70s. Upon her return, she declared: Canada is the best. Thus, they began making annual trips to Canada. Their love for the country became a cornerstone of their lives. They brought pieces of Canada back to Ichinomiya, enveloping themselves in its essence daily and starting each day with the scent of Canada.

I inquired about the pioneer kissa that first introduced morning service with toast and pizza toast, but Sakai had no specific details. “There’s no original,” he remarked. At least, no one specific place is acknowledged. The discussion seemed of little importance to him. He gestured toward the wall lined with coffee cups behind the bar. Beside them was a sign: “My cup, three books of tickets.” This meant that purchasing three books of coffee tickets allowed you to choose your own cup, which would be yours for life. It was an investment of about 9,000 yen, roughly $82. “Regulars,” Sakai stressed, “are everything. I know each regular, where they sit, how they like their coffee, which cup is theirs.” I was captivated by the cup concept and found myself yearning for my own.

Canadian Coffee House closed at noon on Sundays, and it was already 1:30 p.m. The other patrons had departed long ago, leaving just Sakai and me in conversation. I apologized for extending his hours, but he looked at me as if I were mad. It was his pleasure. This is what kissa are all about — community, connection, conversation, and unexpected moments. I reached for my wallet, but he told me it was too late. He had already closed the register. “It’s no longer possible for you to pay today,” he said. A true gentleman and savvy businessman.

As I was leaving, I paused in the parking lot to take one final photo. At that moment, Sakai emerged from the door to close it — it had been ajar to let fresh air circulate through the shop. I captured the moment. His posture was flawless. One could imagine his internal organs perfectly aligned.

Mr. Sakai pulls the door shut at his kissa, Canadian Coffee House

Mr. Sakai pulls the door shut at his kissa, Canadian Coffee HouseI’m fully aware of the absurdity of my quest. I was attempting to understand a country by trekking hundreds of kilometers between aging cafes, subsisting almost entirely on pizza toast.

The detour through Nagoya didn’t shed much light on the dish’s origins. However, Otake, the expert on Nagoya kissaten, shared his hypothesis: Ichinomiya and Nagoya once thrived as a garment district during the Showa era, with Nagoya serving as a port for postwar American wheat imports. The garment factories were so noisy that workers and managers required meeting spaces. Thus, the kissa emerged. Since these meetings occurred in the morning, morning sets became popular. And with the influx of wheat into Nagoya, bread became a staple.

Regardless of what Nagoya and Ichinomiya might or might not have revealed, my continued journey was filled with pizza toast.

There was the meticulous creation of Uda Toru at Mugi & Mame in Honjo, Saitama. After studying bread-making in France for five years, his pizza toast featured homemade, yeasty bread; bacon bits; green and yellow peppers; gouda cheese; onions; all scored for easy tearing.

Then there was the basic cheese toast at the back of a hair salon at Takano Coffee. That day I walked 47 kilometers, and while my feet and shoulders ached, I vividly remember the broad smile and bald head of the hairdresser turned part-time kissa owner, who served his toast with great enthusiasm.

The pizza toast from Mugi & Mame

The pizza toast from Mugi & MameThen there was Shimura Michiko’s pizza toast, the only female kissa owner I encountered. At her shop, Kotoriya, located just outside Nakatsugawa and open for 17 years, pizza toast wasn’t on the menu. However, when I inquired, she prepared it for me: a zesty green pepper tomato sauce mixed with egg salad and a hint of togarashi pepper. No other pizza toast had such a unique punch. She repeatedly apologized for the ‘basic’ nature of her pizza toast, explaining that while it used to be on the menu, its lack of popularity led her to remove it, despite her fondness for making it. Her shop’s mission: “To create a healing environment.” I told her I felt both healed and nourished, expressing my gratitude for the rare off-menu gesture of kindness.

There was the utterly simple pizza toast from Enmado near Kusatsu. It featured green peppers, onions, and American cheese, with half the crust removed. Little sticks of pizza toast bliss served at a small kissa where regulars chatted away.

Then came the plum tea served with toast and an egg at a quaint kissa named Yakkogasa (intriguingly translated as “manservant umbrella”) outside Sekigahara. The plum tea was a surprisingly tart palate cleanser. It didn’t replace coffee, which was also served, all presented on a lovely piece of china. This plum tea and coffee duo had been a tradition for 39 years.

Then there was Kumata.

It was clear that many of the kissa I visited during my extensive walk would soon shutter their doors. The few that remained often resembled quaint retirement homes or community hubs, serving as gathering spots for the dwindling elderly population of rural towns and villages. This wasn’t disheartening but rather a reflection of changing demographics and globalization. It seemed emblematic of a broader trend in contemporary life; small, personal joys often feel over-optimized, while kissa—with their business models, scales, and menus—are strikingly under-optimized. They seemed destined to fade away with the older generation.

The Kiso-ji valley represents the longest stretch of picturesque scenery on the Nakasendo route, taking roughly five days to traverse. It starts near Shiojiri, where the valley walls flank the road as you head southwest. Some villages along the way thrive on tourism, while many others are nearly deserted. Most kissa I encountered were closed, and those open had adjusted their menus to cater to tourists, featuring a traditional Edo-era dish called zenzai: grilled mochi rice cakes covered in hot red bean paste, served in a bowl of soup with pickled radish on the side.

Scattered throughout the Kiso-ji valley are 'barrier towns'—historic checkpoints from the 1600s where permission was required to travel within the country. After walking for nine hours, I reached the barrier town of Kiso-Fukushima. That day, kissa had eluded me from dawn till dusk, and I had resigned myself to the absence of toast or coffee. But just before arriving at my evening accommodation, I caught sight of Kumata.

At 6 p.m., the sign on Kumata's door said 'closed,' but I knocked and entered anyway. Inside, an elderly man wearing a black bandana adorned with skulls and crossbones was seated at the dimly lit bar counter. He glanced up as I apologized for my intrusion, inquiring about morning hours. Mr. Bandana, the owner Mr. Kumata, welcomed me with no hesitation into his eclectic parlor decorated with Native American posters, Winnie the Pooh stuffed animals, dolls, and old magazines.

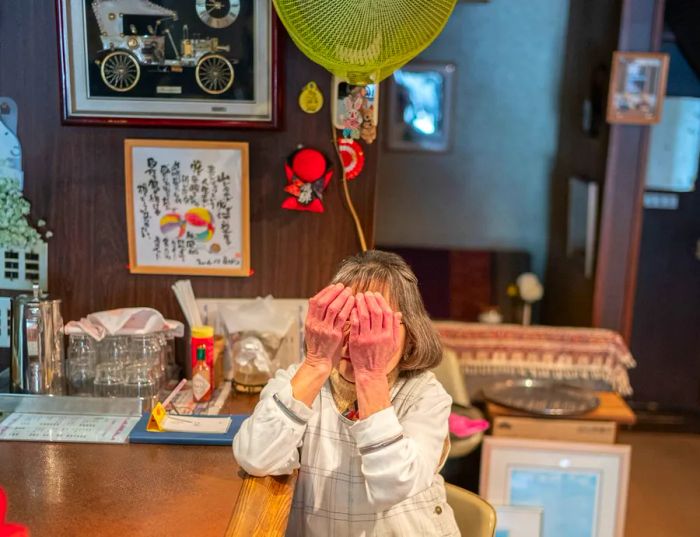

Mrs. Kumata, affectionately known as 'Mama,' managing the kissa she operates with her husband

He grinned as if I had posed a tricky question. He mentioned they were planning a day off the following day but could open just for me in the morning. They had a child's piano recital to attend, but that was not until later—he glanced at his wife, who was just shy of 5 feet tall and standing behind the counter. 'Come by at 9 a.m.,' he said. 'We'll be expecting you.'

I inquired about their pizza toast, and they did have it. They chuckled, finding it amusing that out of everything on their menu, I singled out pizza toast. Nevertheless, they promised to be prepared for me.

So, it was quite a surprise when the next morning they served me an entire pizza. 'We didn’t think you’d want just pizza toast,' Mrs. Kumata — who preferred to be called 'Mama' — said as she brought out a thin-crust pizza. I didn't have the heart to explain that pizza toast was my ultimate comfort, a symbol of my journey, a culinary unifier. Pizza toast was more than just food; it was a quirky slice of cultural history, a symbol of resilience. And above all, it was delicious.

But I kept those thoughts to myself. I gratefully accepted their generous offering with a big smile and perhaps a tear or two, enjoying a pizza for breakfast. This pizza, topped with ketchup, sausage, onions, and three kinds of cheese, was the most heartfelt meal I’d ever had. As I ate the soft pie, they shared stories of their lives with me:

The Kumatas have been running this kissa for fifty-two years. Mr. Kumata, originally from Tokyo, moved here during the war to escape the firebombings, while Mama, a local with a notable father, remained. They’ve been married for 58 years, still laughing and acting like newlyweds, despite being in their 80s and skiing at least 30 times a season. 'We need to get our money’s worth from the season lift ticket,' they joked.

They have children and grandchildren, all residing in Tokyo 'where the opportunities are.' I asked if their kids would take over the kissa when they were gone, and Mr. Kumata shook his head. No, he said, they had raised their children well enough so that they wouldn't have to run a kissa.

The shop was brimming with trinkets and curios. I explored a bit, finished my pizza, and ordered some toast. I couldn’t bring myself to request pizza toast. When the toast arrived, Mama performed a little dance for me. Her knees, still strong from skiing, were impressive. The toast was classic, thick-cut Japanese white bread—top-notch kissa toast. I adored it, and them.

Sitting in the dim, cool atmosphere of the Kumata kissa, surrounded by stuffed animals and a faux fireplace, I felt a sense of healing. The journey seemed to be coming to a peaceful resolution, and even though there was more Pachinko Road ahead, it felt distant for now. I was thankful to be directly witnessing the essence of kissa culture. Though its time was fleeting and I couldn’t save it, being a part of it felt meaningful.

The distance left to walk that day was somewhere in the 30s. I hesitated, as Mr. Kumata was eager to continue our conversation. 'Stay,' he urged, wanting to share more stories, but Mama intervened. She gently guided me by the elbow toward the door. Her head barely reached my bicep as she winked and said, 'Let the boy walk, darling.'

Craig Mod is a writer and photographer based in Japan.

1

2

3

4

5

Evaluation :

5/5