In remote Alaska, meal preparation is essential

In March 2020, as pandemic lockdowns began and everyone scrambled to stock up on groceries for the weeks ahead, I was fortunate to have a chest freezer brimming with food and a pantry filled with months' worth of meals in my Fairbanks home. After over a decade in the Arctic, my time in the fly-in community of Bettles, Alaska, had equipped me for this new way of life in ways I hadn't anticipated.

In 2010, I relocated from Brooklyn to Bettles to join my husband, Adam, who had been a park ranger at Gates of the Arctic National Park for about 15 years. Bettles sits on the Koyukuk River, 35 miles north of the Arctic Circle, serving as a seasonal hub for park workers and visitors embarking on backcountry adventures. The welcome sign that greets those arriving by Cessna reads, “Population 63,” although I doubt the number of full-time residents has ever exceeded 30 or 40.

Access to Bettles by car is only possible during winter when the river freezes and forms an ice road, reminiscent of the routes featured on the reality show Ice Road Truckers. In summer, there are two daily flights from Fairbanks that take 90 minutes; after that, visitors can charter flights into the park. In winter, it’s possible to drive the ice road from Fairbanks, provided conditions allow.

Bettles originated as a gold rush trading post on the west bank of the river, but in the late 1950s and early 1960s, residents moved to what’s known as “new” Bettles, a 2-square-mile area near the newly built airstrip, previously recognized as the unincorporated Alaska Native village of Evansville. Nowadays, an invisible line separates Evansville from Bettles, which affects residents primarily during local elections. The 10 to 15 inhabitants of Evansville are mostly Alaska Native, while the 20 or so residents of Bettles are largely non-Native, drawn here for work — mainly at the FAA weather station, the National Park Service, or the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. In summer, Bettles’ population can double with seasonal workers, but for the most part, these two areas have merged into a single community.

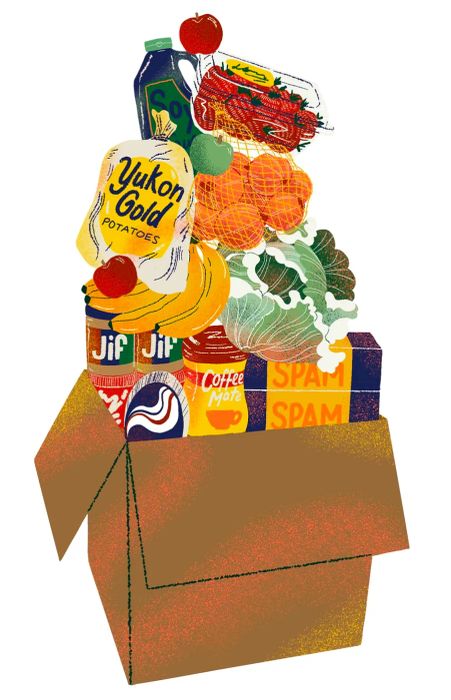

Bettles is one of many rural Alaskan communities, predominantly Alaska Native, that remain isolated from the continental supply chain. Various industries, such as fishing, timber, and oil, require residents to inhabit remote work or fishing camps. Seasonal pantry stocking with non-perishable goods is a vital aspect of the state's food culture. Moving to a rural area like Bettles fundamentally alters how one thinks about food procurement and community building around shared meals.

During my first summer in the Arctic, Adam, who had already spent several summers in Bettles, arrived a few weeks prior and insisted I stock up on groceries in Fairbanks. What he truly meant was to buy as much food as I could fit in a cart, transport it back to my hotel, repackage it into boxes, and then take it to the small Bush plane office to be shipped as freight.

What Adam hadn’t mentioned—yet quickly became second nature to me—was that in our small town, we would create our own eating rituals. While fresh strawberries would be scarce, we’d find innovative ways to accomplish tasks that would be simpler elsewhere. We’d grow vegetables with neighbors, order food from far away weeks in advance, and rarely eat alone.

Historically, the Alaska Natives in this region—Iñupiat and Athabascan peoples, many of whom were nomadic—relied on the land for sustenance, now referred to as “subsistence” in Alaska, consuming berries, moose, fish, caribou, and Dall sheep. Many Alaska Native communities still use subsistence to supplement their pantry and mitigate high food costs. However, in Bettles, I observed that an aging population and the convenience of Amazon Prime have made these traditional food-gathering methods less common.

Today, when flights arrive in Bettles, up to 50 Amazon packages are tossed from the plane’s cargo shoot onto the pickup truck serving as a mail vehicle. The Fred Meyer grocery store’s Bush order boxes are handled with great care, like precious cargo, by eager locals. Amazon likely incurs substantial losses shipping bulky food items to Bush Alaska, where, in addition to the USPS or UPS costs to transport each item to Fairbanks, it costs 79 cents per pound to fly it from Fairbanks to Bettles. I often chuckled and shook my head when unboxing a large delivery of coconut milk I received via Amazon Prime with free shipping—it probably cost them at least $15 to get it to me.

The only grocery store in town, run by a flight shuttle service, operates solely during the summer. It's about the size of a mid-sized walk-in closet, stocked with the cravings of those returning from 10 days in the backcountry—think frozen pizzas, ice cream sandwiches, microwavable mac and cheese, and Jimmy Dean breakfast sandwiches—especially when the midnight sun keeps people awake.

Transporting frozen foods to Bettles is quite the challenge, and it's impressive that ice cream sandwiches and rocket pops are still priced at just $1 each. It seems the shop owner wants everyone to enjoy ice cream in the summer without marking up the price. The shop often relies on an honor system where you jot down your name and what you took in a notebook or leave cash in an envelope. By summer's end, I'm always surprised to find I owe $62 for Almond Joys, raspberry popsicles, and Fritos.

Hazel Pagkalinawan first arrived in Bettles from Southern California nearly 15 years ago to manage the Bettles Lodge, a historic small hotel right at the airstrip. Since then, she has served as a relief cook at the lodge, a weather observer, vice mayor, and currently, the city clerk.

As I speak with Pagkalinawan just before Easter, she mentions that several families are planning a potluck brunch this year. Potlucks in Bettles, especially during spring and summer, are common, as they not only allow the community to share resources but also help alleviate loneliness. One family will prepare sourdough pancakes, another will bring an ambrosia dessert from an old recipe, and Pagkalinawan plans to make a frittata and possibly ribs, depending on whether her grocery order arrives on the plane that day. “I also ordered Cool Whip for the dessert; if it doesn’t arrive, we’ll make do with what we have,” she adds.

Pagkalinawan’s pantry is filled with items from Amazon Subscribe & Save (flour, sugars, canned beans), and this year she made a trip on the ice road to bring back sodas, alcohol, and other heavy items that Amazon doesn’t provide. She had to cut our conversation short to call the flight service and check if her “freshies” (the local term for fresh food orders) from Fred Meyer would land that day.

In recent years—largely due to the pandemic—it has become a bit easier to place Bush orders at the grocery store. Fairbanks offers several grocery options, but most Bush orders go through Fred Meyer, part of the Kroger family. In fact, it was these orders that helped make “Fred Meyer West, one of two Fred Meyer locations in Fairbanks, the top-grossing Kroger supermarket in the nation—outperforming over 2,700 other stores” in 2016, as reported by the Anchorage Daily News.

Just five years ago, placing an order involved calling the Bush order desk, reading your list to whoever answered, paying over the phone, and hoping for the best. Would you get green grapes or red? How many would you even receive? Would the bananas be ripe or still green? Bettles lacks cell phone service; only landlines are available, and during our early years, we didn’t have a landline at home. We relied on a pay phone at the Bettles Lodge or one in a makeshift Park Service game room that somehow remained connected.

Pagkalinawan estimates that between the additional fees Fred Meyer charges for packaging her order and the freight costs for her groceries on the flight, she ends up paying about $100 extra on top of the actual order price. Despite this, she places an order every three or four weeks, as she prefers not to rely on frozen vegetables: “I buy vegetables that last, mostly cabbage. If something is going bad, I cook it first,” she explains.

In a place like Bettles, freezers are essential. Most residents have at least two freezers—and some even have two refrigerators—which are especially useful when there's an influx of moose or caribou meat. Although subsistence hunting isn't a primary food source anymore, non-residents can hunt with a guide in the adjacent national preserve (not the national park) or with a permit on state land. Hunters often stop in Bettles before flying to Fairbanks, leaving behind a portion of their meat—excluding prime cuts and trophy parts like heads or antlers. When animals are hunted illegally, the state donates the meat to nearby communities. A local, often the first person to answer the phone, then distributes the moose legs and caribou quarters, ensuring everyone has a well-stocked freezer. Last year, Pagkalinawan said, “I turned down meat donations because I had no room; I still had plenty.” This surplus frequently appears in her potluck favorites, like moose lasagna and moose enchiladas.

Creating a delightful potluck dish with just what you have on hand feels like a Top Chef challenge, where you must craft a menu from four selected ingredients. In a pinch, you might call a friend to borrow an essential item. When invited to a potluck (which can occur multiple times a week during peak summer), I aim to prepare something that can feed a crowd, appears intricate but is simple to make, and preserves any prized ingredients (like fresh fruits and vegetables)—such as corn bread with a hidden spice (cumin or za’atar), or Peruvian chicha morada (from a packet I brought back from my travels) mixed with a splash of vodka (Bettles is a “wet” village, though many Arctic communities are “dry”). Rice is always a safe potluck contribution; I promise it will be appreciated.

Regardless of the specific dishes that appear on the potluck table, ensuring that Native elders are well-fed remains a community priority. It’s common to hear someone say, “I’ll make a plate for...” as the potluck wraps up and leftovers start to be shared out.

By my second summer in Bettles, I had devised a more sustainable approach to eating. The town experiences extreme variations in both temperature and daylight. Winters can plunge to minus 40°F with just three to four hours of light, while summers offer nearly 24 hours of sunlight and temperatures ranging from 70 to 90°F. This allows for rapid and plentiful gardening, so I planted a variety of lettuce, kale, chard, carrots, tomatoes, and as many herbs as I could fit in the space available.

I discovered a sourdough starter and began baking bread (with flour sourced from Amazon), along with jellies made from the plentiful blueberries and cranberries we gathered in August. Using his brewing equipment, Adam managed to produce enough beer to last through most of the summer. We started bringing salads and blueberry muffins to potlucks.

Pagkalinawan pointed out, “Visitors to Bettles are often surprised by how well we eat. I tell them that we can’t just pop into a restaurant; we know what we want and must plan accordingly.”

A friend from New York City, an amateur chef studying food systems, came to visit, and we organized a potluck with a local theme. Adam caught grayling from the river, served over sautéed greens with a rhubarb sauce. Our neighbors contributed moose burgers, locally grown potatoes infused with our garden’s rosemary, and blueberry cobbler. We stayed up late—something hard to grasp during summer's endless daylight—sharing food and sipping Bota Box wine. Although it was a gourmet feast, it felt as satisfying as the countless meals of hot dogs and macaroni salad we’d shared before; the quality of a meal reflects both the company and the effort it takes to prepare everything. Before heading to bed, as the sun dipped near the horizon, we strolled to the small shop on the airstrip to cap off the evening with Mounds bars and Doritos.

Bree Kessler is a writer, researcher, and advocate for public spaces, residing in Alaska and Hawai‘i.Rejoy Armamento is an illustrator and mural artist based in Anchorage, Alaska.Copy edited by Paola Banchero

1

2

3

4

5

Evaluation :

5/5