In Utrecht, Pursuing an Art Movement Aimed at Mending the World

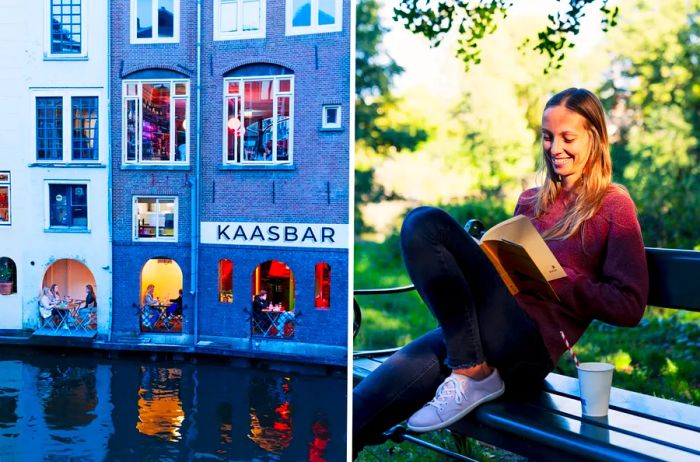

Utrecht is often described as the destination for experiencing the charm of Amsterdam without the overwhelming crowds. The city boasts tree-lined canals, quaint streets, and a pleasant atmosphere, all with far fewer tourists. Located 33 miles from the capital, Utrecht is an ancient trading hub turned university town, seamlessly blending history with a modern edge. Its old wharf cellars have been transformed into cozy cafés, restaurants, and apartments lining the canals. Stylish students gather beneath willow trees, engaging in lively conversation. I observed two women in scarves, cycling at the Saturday flower market, tucking tulips into their baskets as they pedaled away hand in hand. It's a sight you might never encounter in the United States.

It felt like a grave error not to be born a Utrechtian, but I had larger thoughts occupying my mind—thoughts steeped in history and complexity. I had come to explore a revolution that transpired here a century ago, driven by a diverse group of artists, designers, architects, poets, and musicians. They referred to themselves as De Stijl—‘the style’—and between 1917 and 1931, they believed they had uncovered a pathway to global harmony, one defined by geometry and color.

By the early 20th century, these artists felt the Netherlands was still entrenched in the 19th century, bogged down by history and overly reverent to tradition. As I cycled around on my first day, I envisioned the dark, chandelier-adorned homes, the towering ancient churches, and the prevailing bourgeois values of the time. In approximately 45 A.D., Emperor Claudius designated Utrecht as the northern frontier of the Roman Empire, leaving behind medieval remnants that coexist with baroque, Gothic, Renaissance, and romantic influences. I imagined the De Stijl artists—Theo van Doesburg, Bart van der Leck, Robert van’t Hoff, Jan Wils, Jakob van Domselaer, Piet Mondrian, and others—cherishing this city yet yearning for change, eager to leave behind the unending sight of bell towers. Then I envisioned everything bursting forth in a brilliant explosion.

I cannot claim to comprehend the chaos and devastation wrought by World War I across Europe. Twenty million lives lost. The very foundations of civilization crumbled. The experience of being isolated in the Netherlands during those four years—while the country remained neutral—meant witnessing a new dimension of restlessness unfold. As these artists began to connect, a shared realization took root: a fundamentally broken world requires a radical transformation.

When it comes to short-lived avant-garde art movements, it’s nearly impossible to underestimate the impact of De Stijl. Though there were few followers scattered throughout Utrecht and the rest of the Netherlands, the artists of De Stijl became a formidable force in the evolution of 20th-century modernism. Piet Mondrian, the most renowned member of the group, is now celebrated as one of the world’s most iconic painters. Without the influence of De Stijl, we wouldn’t have the Bauhaus school, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, or the legendary Eames House in Los Angeles. Even today, traces of the group’s impact can be seen in industrial design, graphic arts, and typography.

I’m not an art historian, but my journey to Utrecht was inspired by a transformative moment in history—one of those rare instances when everything suddenly shifts, propelling us from our familiar lives into the unknown. This group witnessed the world fall apart and approached the remnants with sledgehammers. Driven by intellectual curiosity or perhaps something deeper, I yearned to absorb that spirit, to grasp it and understand it. Their endeavors struck me as both beautiful and perplexing, prompting me to book a room and embark on my quest for understanding.

Photos by Jussi Puikkonen

The following morning dawned bright and clear. I cycled past airy cafés spilling onto lively streets, with street art and murals adorning every corner—including a geometric cityscape inspired by De Stijl, painted on a building to the north. In Utrecht’s historic center, an artist had placed a neon halo over St. Willibrord’s Church, which otherwise had a rather grim Gothic-revival appearance. This installation was part of Utrecht Lumen, a series of light displays activated at sunset. One artist seemed to resonate with my desire to trace the unseen threads of history. Near the Domtoren bell tower, colored bulbs illuminated every 15 minutes while steam billowed from the street, highlighting what once was the edge of an ancient Roman fortress.

I can’t say that all of these installations felt distinctly De Stijl, but perhaps they were a distant echo of what De Stijl had unleashed. Just months after establishing itself, the group launched a magazine and released a comprehensive utopian manifesto. “The war,” they asserted, “is dismantling the old world and its contents: individual dominance in every state.” They argued that representative art, which emphasized subjective perspectives, had to be abandoned. Through abstraction and a strict set of rules—only primary colors, with horizontal and vertical lines allowed but no diagonals or circles—these De Stijl artists aimed to distill art to its universally recognizable and spiritually genuine essence.

As I rode my bike around, I envisioned a previously stifled town buzzing with innovative ideas. The De Stijl artist van Doesburg developed a completely new alphabet, with each character determined by mathematical principles. Mondrian played with simple, off-white grids, while van der Leck began sketching human figures and then covering them in white paint, allowing only fundamental geometric shapes to emerge. Around 1919, Gerrit Rietveld would create his iconic Red Blue Chair—the first significant three-dimensional expression of De Stijl, a piece so influential that the American architect Philip Johnson eventually donated one to the Museum of Modern Art in New York City.

Photos by Jussi Puikkonen

I wanted to experience De Stijl up close. So, on my second morning, I pedaled to an industrial area filled with nondescript warehouses. Upon reaching the address written on my hand, I pressed a buzzer, and an unmarked door swung open.

Due to some renovations at Utrecht’s Centraal Museum, the De Stijl collection was not on display during my visit. However, I managed to arrange a private viewing of the depot where the museum stores its off-exhibit items. The woman who welcomed me, named Chantal, insisted on a promise that I would not reveal any details about the location. She then guided me down a long hallway to a gray metal door. We entered a vast, quiet space filled with thousands of paintings hanging closely on massive sliding panels, arranged in long rows. Adjacent to this room was another equally expansive space, and then another, and another.

For the next two hours, I enjoyed a personalized De Stijl tour. Here were private sketchbooks documenting van Doesburg’s artistic journey, and there was a grid of somber squares and partial circles painted by César Domela-Nieuwenhuis. Tucked away on a shelf, much like someone’s old ski equipment, was Rietveld’s Red Blue Chair.

For years, I had gazed at these artworks on a screen—partly, if I’m honest, in a state of confusion. The philosophy of De Stijl seemed inscrutable, almost mystically cryptic to me. (At one point, van Doesburg encapsulated Mondrian’s ideas with the phrase: “vertical = male = space = statics = harmony; horizontal = female = time = dynamics = melody, etc.”) Yet now, with my nose just inches from the canvas, I recognized something deeply human in these works. Behind this orderly red line lay the trauma of war. In that configuration of rectangles, I saw not mere geometry but a profound sense of hope.

Chantal revealed another panel, and I gazed at a Tangram-like array of shapes, a piece by the Hungarian artist and graphic designer Vilmos Huszár, who had made the Netherlands his home. The typical criticism of abstract art is that it feels sterile, lacking emotion. However, in the simplicity of this painting, I perceived something different: a mind eager to dismantle a shattered world down to its core and rebuild it anew.

Eventually, I bid farewell and cycled back to my hotel. This endeavor of mine—tracing the faded footsteps of this long-gone art movement—had often been difficult to articulate to myself. Yet, it became clear: I was in a beautiful city where some individuals had taken a bold, unconventional leap. Was it so absurd, I pondered, to believe that society could be reshaped through shapes, lines, and colors? Well, yes, it might be. But I also believe that irrational conviction is one of humanity's most remarkable traits, while demanding logic from it is one of our greatest failings.

I found the philosophy of De Stijl to be puzzling, almost shrouded in a mystical enigma. Yet now, standing just inches from the canvas, I discerned something distinctly human within these works.

During the following days in Utrecht, I experienced everything through the lens of De Stijl. In a rowboat on the Oudegracht (old canal), a family set up a mobile picnic—how would van der Leck have captured this moment? The moorhens idly bobbing in the Nieuwegracht—can their essence be portrayed in a less subjective, more universal manner? One afternoon, I sprawled on the grass at Máximapark, located west of the city center. All day, I had been listening to a solitary piano suite by composer van Domselaer, stark and foreboding, and there on the ground, I felt it partition the sun, the trees, and the pathways into Mondrian-esque segments of existence.

Photos by Jussi Puikkonen

I also observed the elements of Utrecht that owe their existence to De Stijl. On a quiet Sunday morning, I knocked on the door of a house situated in a cul-de-sac behind St. Peter’s Church. A tall, graceful woman opened the door, a gesture she has extended to strangers every month for several years. Architect Mart van Schijndel acquired this former glazier’s warehouse in the 1980s and spent the next six years crafting a new type of home and a new lifestyle. Tragically, four years after receiving the prestigious Rietveld Award in 1995, van Schijndel passed away. Natascha Drabbe, his wife, wished for their creation to remain alive in the public consciousness. Thus, one Sunday each month, despite still residing there, Drabbe opens the Van Schijndel House to visitors.

Upon entering, I immediately recognized the unmistakable influence of De Stijl: the vibrant colors and the interplay of vertical and horizontal planes. Yet there were also striking departures from tradition. The design revolved around a triangular floor plan, allowing light to flood in from every angle. As we explored, Drabbe, an architectural historian, highlighted how subtle choices—window placements, angles—can reveal an entirely new perspective. I found myself not in a historic structure or city, but in a sanctuary of light and geometry. At one moment, we stood observing shadows dance along a staircase, feeling once again the invisible forces that had been set in motion decades earlier.

I couldn't deny it: my journey was quite peculiar. Rather than indulging in surfing or sampling wines, I was tapping into distant artistic echoes, envisioning the intellectual fervor of a century past. As fanciful as it sounds, it felt incredibly relevant to the current moment. Travel often serves as a gateway to the obscure, allowing us to connect with unfamiliar frequencies. Sometimes, what you truly need is a immersion in red and blue rectangles and a quest for a world long gone.

It wasn't merely an abstract endeavor. That week, whenever De Stijl became too theoretical for my limited understanding, I thought of Truus Schröder-Schräder, a native of Utrecht whose interaction with De Stijl felt refreshingly tangible. In 1911, Truus married Frits Schröder, a lawyer eleven years her senior. He embodied traditional values in a conventional world. Meanwhile, she was a 22-year-old filled with creativity and modern ideas, yet deeply unhappy. Frits had promised her a life of freedom—no children, space to express herself—but instead delivered the conventional expectations of bourgeois Dutch family life. "He made me all sorts of promises, but he didn’t keep them," she later reflected. "He basically deceived me into this life."

Trapped in a life, a home, and a city that felt foreign to her, Truus found herself confined to a world not of her making. Then, in 1923, tragedy struck with Frits's passing. As De Stijl began its cultural renaissance, Truus embarked on her own. She left behind her dreary, cluttered home and started anew with her three children—not just a fresh start but a completely different way of life. She enlisted Gerrit Rietveld, a rising star within the De Stijl movement, to design a home tailored for her needs.

"How do you envision your life?" he asked her at the outset.

It seemed a natural inquiry for an architect to pose to his client. However, the question of how one wished to live had been firmly decided for so long—especially for a woman—that Schröder-Schräder suddenly found herself with an unprecedented gift: options. In the years that followed, the Rietveld Schröder House emerged as the sole livable embodiment of De Stijl principles, a groundbreaking example of modernist architecture. Today, it proudly stands as a UNESCO World Heritage site.

On my penultimate day, I cycled to the house, a petite white structure located on the city's outskirts. A small crowd had gathered on the sidewalk, quietly snapping photos as if they were capturing a glimpse of a celebrity.

Inside, sunlight illuminated a series of white and gray surfaces. The sharp lines created a striking contrast with the fluidity of the spaces, making me feel as though I had stepped into a Mondrian painting. Schröder-Schräder insisted that the distinction between inside and outside should be blurred. Movable walls and adaptable rooms defined her vision. Her favorite spot was the top floor, offering sweeping views of the surrounding landscape. Rietveld even installed a speaking tube for her, allowing her to converse with visitors at the door without needing to descend the stairs.

At one moment, the docent at the house gathered us at the top of the staircase. We clustered around as she reached for a pristine white wall, gently sliding it along a track to recreate one of the children's bedrooms, just as Schröder-Schräder would do every night. During the day, she would push it back to open up the upper floor. It may seem like a trivial feature—a movable wall—but it sparked a realization for me.

Photo by Jussi Puikkonen

While De Stijl could sometimes seem impenetrably abstract, I recognized its principles as concepts that would influence a real person's life—her meals, her mornings. In times of upheaval, when the world dictated so much of one's fate, a touch of freedom might bring one closer to harmony. And undeniably, harmony had flourished here. Thirty-two years after Schröder-Schräder took up residence, Rietveld—by then a renowned figure in De Stijl—joined her. Their partnership blossomed into love, and they spent the rest of their lives together in that house.

Radical and particular art movements are fragile. When van Doesburg dared to introduce diagonal lines into his artwork, Mondrian left the group in protest in 1923. Just like that, a yearslong friendship was fractured over the angle of a line. The movement began to acquire a more global character, sometimes blending with dadaism, and when van Doesburg passed away from a heart attack in 1931 at the age of 47, De Stijl essentially came to an end as well.

On my final day in Utrecht, a gray sky loomed low over the city. I bundled up and rode my bike towards the Hogeweidebrug, an arched bridge connecting the city with the western suburbs, while listening to van Domselaer once more, his chords tense and fractured-sounding.

I’m willing to assert that De Stijl's ambitions didn’t fully materialize. However, instead of transforming society, perhaps De Stijl initiated change on a smaller scale—a person contemplating the mere possibility that a grid could possess mythical significance, a woman sliding open walls each morning to live on her own terms.

As I approached the Hogeweidebrug, a raucous crescendo began to build. I pedaled harder. Below me, the Amsterdam-Rijnkanaal stretched wide and slate-colored, while a barge laden with rusty river debris navigated solemnly northward. On the far side of the river, a man sat by a lamppost, sketching. A woman pushed a stroller with one hand while texting with the other. Van Domselaer's music erupted, jamming dissonant notes together, devoid of embellishments—just the raw essence of something deeply unsettling. Perhaps reshaping reality is an ambitious goal, but sometimes, you discover a crack in it, and with ink, paint, chords, and blueprints, you can widen it a little.

Evaluation :

5/5