Ivar’s the Legendary

TodayToday the sun shines brightly on this 55-degree Tuesday in March, making Seattle feel like it's on vacation. Moms push strollers, hot dog vendors call out, and groups of teenagers cluster along the waterfront. The distant cries of seagulls mix with the hum of voices and the murmur of cars searching for parking. I continue my stroll past the aquarium, souvenir shops, and a candy store until I reach Pier 54. Here, I discover that the gulls have chosen the perfect spot on the waterfront: the seafood bar at Ivar’s Acres of Clams.

Outside the restaurant stands a statue of Ivar Haglund, the founder of Ivar’s, feeding french fries to a flock of hungry seagulls. Years ago, a nearby business put up signs urging people to stop feeding the birds, as they were growing increasingly demanding and aggressive. In response, Haglund put up his own sign near the outdoor seating: “Seagulls welcome! Seagull lovers invited to feed seagulls in need.” A version of this sign still adorns the area today, though it now includes a note advising against feeding pigeons or birds that enter the covered dining space.

During my last visit, when my mom was still living in Seattle, the area was dark and deserted. But now, thanks to the $688 million overhaul aimed at making the waterfront more pedestrian-friendly and inviting to tourists, the place has undergone a dramatic transformation. The old Alaskan Way Viaduct, an elevated freeway that once cast a shadow over the bustling area, is being demolished. In its place, green spaces, bike paths, and improved connections between Pike Place Market and other waterfront attractions like the aquarium, Ferris wheel, and numerous souvenir shops are emerging.

At Ivar’s, you’ll find classic offerings like chowder, clam bellies, and fish and chips

At Ivar’s, you’ll find classic offerings like chowder, clam bellies, and fish and chipsOld and new clash in a tense standoff. Onlookers crowd the sidewalk, phones extended, capturing the demolition of the Viaduct across the street. I join them, watching as machinery rends concrete like a ravenous beast. It’s a rare moment when a city redefines itself, and Seattle is striving to offer the perks of a sprawling metropolis like New York while avoiding the oppressive concrete canyons. The tourism board even coined a term—'Metronatural'—to describe the mix of clear skies, vast waters, and urban hustle. Though the slogan was mocked, it didn’t deter newcomers. Seattle is now a tech hub where the waterfront often feels like a mere backdrop. The old canneries and fishing suppliers have been replaced by waterfront restaurants serving seafood.

A crowd gathers beneath the glowing ‘Ivar’s Fish Bar’ sign as I approach to place my order. The menus boast a faux-chalkboard design, and the word ‘SEAFOOD’ is stenciled on the small tiles below the counter. My anticipation is high as I return to Ivar’s after many years, but a nagging worry lingers—will this bowl of chowder measure up to my childhood memories? Sometimes nostalgia makes the past seem sweeter than reality.

Here’s the original Ivar’s Acres of Clams from the 1940s, adorned with neon signs galore.

Ivar’s

Here’s the original Ivar’s Acres of Clams from the 1940s, adorned with neon signs galore.

Ivar’sIvar’s Acres of Clams has been a fixture since the late 1930s, marking the beginning of a now-statewide chain with 21 seafood bars and two additional restaurants across Washington. Over the past 80 years, Ivar’s has cemented its place as a Pacific Northwest icon. However, Acres, with its premium pricing ($25 for a salmon Caesar salad or $68 for a lobster tail surf and turf), has become a tourist magnet. Locals know to head to the walk-up counter next to the restaurant for a more casual dining experience, with tables both covered and uncovered to handle the frequent Pacific Northwest rains.

At Ivar’s fish bar, you get the quintessential waterfront fare: chowders, seafood cocktails, and crispy fish and chips. The fish and chips are exceptionally light and crisp, with batter clinging to the cod fillets perfectly—almost as if the cod were swimming in the crunchy coating.

The bar serves a selection of chowders: the classic white, with just the right hint of bacon flavor without overwhelming the clams; a smoky salmon chowder; and a vibrant red chowder with tomatoes. As a purist, I stick with the traditional white. Although chowder is often linked to New England, the West Coast has its own rich chowder tradition. San Francisco popularized the sourdough bread bowl, but the Pacific Northwest, with its rainy winters and abundant shellfish, is perfect for hearty, steaming bowls of chowder—whether clam or smoked salmon. While there are many places to enjoy chowder along the waterfront, for me, Ivar’s represents the taste of home.

At age 9, my family and I relocated to Whidbey Island in Puget Sound, a scenic hour’s drive and ferry ride from Seattle. Our house, draped in shingles and wisteria, featured a pasture with sheep and a peacock who made his morning calls outside my mom and stepdad’s window at 6 a.m. The acoustics there were apparently exceptional.

Those three years on Whidbey Island were the longest I spent in one place during my childhood. The house felt like a magical sanctuary, with memories growing as entwined as the ivy on its walls. My poor sense of direction, I believe, stems from the constant relocations of my youth—thanks to divorce and the shifting tech boom. I never had a chance to settle before moving on to the next place.

The takeout counter at Ivar’s

The takeout counter at Ivar’s The walk-up seafood stand at Ivar’s on Seattle’s waterfront

The walk-up seafood stand at Ivar’s on Seattle’s waterfrontToday, the Ivar’s seafood stand on the waterfront is a bit short-staffed, leading the employees to ask customers to order their fried dishes first, followed by the rest. It's a bit of a muddled system, but it gets the job done. I opt for something intriguingly named “clam nectar,” picturing it as a sort of oyster shooter. The staff call out my order—“Three-piece cod and chips! Cup of chowder!”—then lower their voices to add, “and a clam nectar too.”

In the 1970s, Haglund used to promote clam nectar by joking that men needed their wives’ approval to order more than three cups. It turned out clam nectar was reputed to be a potent aphrodisiac. Could clams, which reproduce without sex, be just shells hiding a lifetime of unfulfilled desire?

The nectar arrives in a paper cup typically used for coffee or tea. Essentially clam broth with spices and butter, it’s both light and rich, offering umami without the heavy texture of a pork broth. It’s delicious, and I keep tasting it, even after sampling other dishes like chowder and chips, to confirm that it’s indeed the nectar that’s so enjoyable.

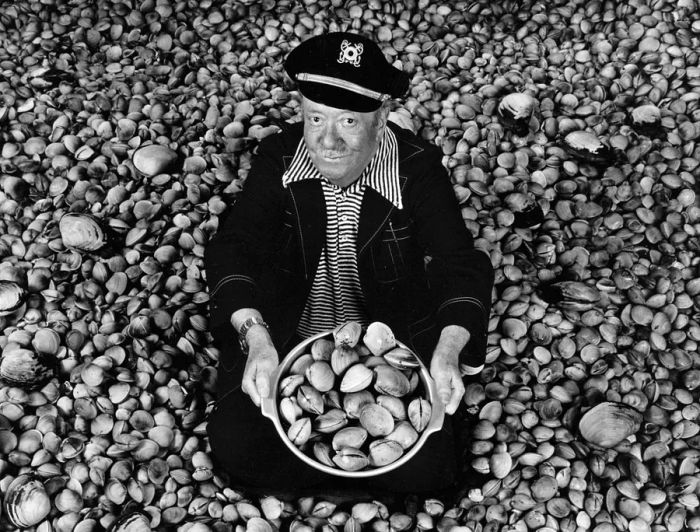

Ivar Haglund amidst his “acres of clams”

Ivar’s

Ivar Haglund amidst his “acres of clams”

Ivar’sHaglund was known for his quirky promotional stunts. In 1947, when a railroad tank car of corn syrup spilled onto the waterfront, Haglund donned hip boots, ordered a large stack of pancakes, and waded into the sticky mess. When reporters arrived, they found him happily spooning syrup onto his breakfast, and the photo made international headlines. Just before the Viaduct’s opening, Haglund hired a brass band to celebrate outside Acres of Clams, thanking the city for its new “acres of covered parking” with a grand show.

Haglund frequently found himself entangled in local politics. In 1976, he bought the Smith Tower, Seattle’s inaugural skyscraper, and proudly flew a custom 16-foot windsock shaped like a salmon atop it. When city officials demanded its removal for a code breach, Haglund responded with a wave of whimsical poetry. Even supporters and some city officials joined in the poetic protest. Haglund’s appeal to the city was a plea not to rush their decision, highlighting the free publicity he was generating. In the end, the board granted approval for the salmon windsock.

Ivar’s stands out as the only restaurant that truly tugs at my heartstrings. Dining out was a rare treat during my childhood—reserved for special occasions like vacations or birthdays. But Ivar’s became a regular spot for me. Each time we left Whidbey Island for Seattle’s IMAX or a shopping trip, we’d board the ferry, disembarking an hour’s drive from the city at Mukilteo Terminal. Famished by the return journey, if we faced a long wait for the ferry—sometimes up to an hour—my parents would give me cash to grab a quick bite at Ivar’s. The Mukilteo Ivar’s, with its waterfront restaurant overlooking Whidbey Island and its seafood bar, had a unique treat no other branch offered: soft serve ice cream. Despite the odd pairing of soft serve and chowder (oh, the cream!), it was a delight for a hungry 10-year-old.

Long-standing establishments like this offer the comfort of routine—a chance to revisit the same flavors as you evolve over time. That’s why something as simple as a bowl of chowder and a scoop of ice cream can become a marker of personal growth. It’s also why I can’t resist clams.

The Mukilteo Landing Ivar’s is the only location that serves soft serve ice cream

The Mukilteo Landing Ivar’s is the only location that serves soft serve ice creamA decade has passed since I visited Whidbey, even though I moved back from the East Coast to Portland three years ago. From my current home, the island is just a four-hour drive away. My mother recently relocated back to Whidbey, years after her separation from the stepfather who raised me. I was 17 when they divorced. He now resides in Seattle, and she is an additional hour away. When I mention him to others, I still refer to him as my stepdad, even if it's not technically accurate. There are numerous terms for family, but few to describe those who remain close despite not being related by blood.

Maintaining a relationship with him has always felt like balancing on a tightrope, a delicate thread I hesitate to tug too hard. I never managed to visit both him and my mom in a single trip, even when they were both in Seattle. The thought of splitting my time between them filled me with guilt, and when they were so close, not seeing both felt like an insult. Consequently, I avoided Seattle altogether, as well as Whidbey Island.

A story assignment on Ivar’s presented a perfect chance to visit them both. I could have made a quick trip—drive to Seattle, enjoy some fish and chowder, and return to Portland the same day. Instead, I stretched it into a week. I first asked my mom if I could visit her on Whidbey after dining at Mukilteo Ivar’s, then reached out to my stepdad about staying with him in Seattle while I explored Ivar’s on the waterfront. He welcomed me with open arms.

Upon arrival, he seemed pleased to see me, even though our phone conversations have grown infrequent, sometimes stretching over a month. Am I overstepping by not wrapping up my visit after my reporting? I suggest meeting for lunch at Ivar’s, but he no longer eats much meat or dairy and has work commitments. “I understand,” I reply, masking my surprise at my own disappointment. I find solace among the gulls at Ivar’s Pier 54 seafood bar, dining solo.

On many days at Ivar’s, kids throw approved food to gulls that swoop in eagerly for fries and fish. The cries of the children blend with the shrieks of the hungry seagulls. Amidst the chaos, I throw my remaining fries one by one and even offer a fry by hand, feeling a peculiar blend of past and present. During childhood visits to my dad, he’d greet me at San Francisco airport with bread for feeding ducks at the Palace of Fine Arts. I’ve since learned that bread isn’t ideal for wildfowl. Whether I stopped feeding them out of concern or nostalgia, I’m unsure. At Ivar’s, the gulls scream for attention but keep their distance, and I manage to avoid any unwanted bird droppings.

The Mukilteo Ivar’s dining area embraces the brand’s nautical theme

The Mukilteo Ivar’s dining area embraces the brand’s nautical themeAfter my solitary adventure to Ivar’s, I head back to my stepdad’s for the night and plan to make my way to Whidbey the next morning. Before catching the ferry, I decide to grab a meal at the Mukilteo Ivar’s. This time, I skip the seafood bar and opt for the sit-down restaurant next door. It’s a spot I never visited during our time on the island, always having meals waiting back home and feeling pressed for time.

In many ways, Mukilteo Ivar’s embodies the charm of classic seafood joints. The walls are adorned with wood, and the bathroom doors feature porthole windows. Smooth jazz plays softly in the background, accompanied by the gentle clink of ice being poured into glasses. The aroma of sourdough from freshly baked rolls fills the air as they are served to each table. My server, a warm woman who seems about my mom’s age, presents me with six Hood Canal oysters on the half shell. She beams with pride when I compliment their taste and shares her own dream of retiring to a house on the river, the quintessential Pacific Northwest fantasy: a woodland home with a backyard oyster bed.

Haglund earned his economics degree just before the Great Depression hit. Rather than pursuing a career in finance, he turned to the rental income from a house he inherited from his father and ventured into folk music. He performed around Seattle, frequently wandering the aquarium he established on the Seattle waterfront—an idea inspired by his cousins who ran a successful aquarium in Oregon—with his guitar and spontaneous songs. Eventually, Haglund landed a 15-minute radio segment on KJR and became a beloved regular on the local children’s show, Captain Puget.

He composed songs about sea creatures, such as “All Hail to the Halibut” and “Run, Clam, Run,” which were really about catching and eating them. One line from the halibut song goes, “Bake it, boil it, fry it, any way you try it, it’s a gastronomical riot.” While he performed these songs celebrating the Puget Sound, his personal favorite was always “The Old Settler”—a gold miner’s tune he supposedly learned from visiting musicians Pete Seeger and Woody Guthrie.

Haglund with his guitar at the aquarium in the 1930s

Ivar’s

Haglund with his guitar at the aquarium in the 1930s

Ivar’sHaglund seemed satisfied with his aquarium and music career until he recognized a new opportunity. Visitors to his aquarium, possibly drawn by the fishy aroma from the nearby boats, often inquired about dining options. This led him to open a fish and chips stand in 1938, which he later expanded into a full-fledged restaurant named Acres of Clams in 1946, borrowing from a line in “The Old Settler.” His inventive spirit and generosity earned him the title “King of the Waterfront.” When Seattle nearly scrapped its 4th of July fireworks in 1964, Haglund stepped up as the sponsor, continuing his support annually until 2008. Upon his death in 1985, he left his company to loyal employees and donated his estate, and the salmon on the Smith Tower flew at half-mast in his honor.

Just like at the Seattle waterfront, my memories of Whidbey Island include places that no longer exist. I ponder whether it's just the specific places I recall that have changed or if the entire landscape has transformed. Decades can alter a lot, particularly for locations between Seattle and South Whidbey. While Seattle thrives with tech giants like Microsoft and Amazon, South Whidbey is also becoming pricier, increasingly popular among wealthy Seattleites seeking vacation homes. I remember a quirky restaurant named Neener Neener Weiner, which we never visited but always amused us with its sign visible from the Mukilteo Speedway. It’s long gone, but I can still picture the statue of a man with a giant hot dog standing outside on my way to Ivar’s.

The menu at the Mukilteo Ivar’s sit-down restaurant offers a range of refined seafood dishes, including seared scallops and steamed mussels and clams

The menu at the Mukilteo Ivar’s sit-down restaurant offers a range of refined seafood dishes, including seared scallops and steamed mussels and clamsFor now, I’m still seated at Mukilteo Ivar’s, picking at the last bits of fried fish on my plate. I pass on dessert and head outside to the seafood bar. Compared to the Pier 54 fish bar, this one is stark and functional, resembling a concession stand at a ballpark as much as a ferry terminal. If any changes have occurred here in the 20 years since I lived on the island, they’re not apparent. I order a kid’s cone, a swirl—my usual choice, though I’m no longer a regular. The air by the waterfront is soon filled with seagulls, possibly stirred up by the ferry’s wake. I wonder what these gulls eat when they're not scavenging for human leftovers. Amidst the chaos, I see a chef in his whites tossing something into the water. He’s feeding the seagulls, continuing a beloved Ivar’s tradition, reminding me that some things thankfully stay the same.

In two hours, I’ll be back on the island. The first question my mother will ask is, “What do you remember?” I find myself overwhelmed by her question and her eagerness to connect. Rather than answering, I’ll tell her the question isn’t very good. “How would you feel if someone asked you to remember every detail from three years of your life?” I’ll respond. “I remember a lot of things.” And I do, though I don’t share many of them with her. I’m unsure where to start.

When I was 10, just before our final departure from the Pacific Northwest as a family, I took the stage at the Whidbey Island talent show. I can’t recall how the song was selected or why I chose to perform it a capella in such a vast auditorium, but I sang “The Old Settler” with gusto. The song tells the story of a tired gold miner who has witnessed many of his peers end up destitute far from their homes. It goes, “I made up my mind to go digging for something a little more sure.” So, he abandons his mining tools and heads to the Puget Sound, where he finds peace, “no longer a slave of ambition,” surrounded not by gold but by fields of glorious clams.

Tove Danovich is a freelance journalist and former New Yorker now based in Portland, Oregon. Connect with her on Twitter, @TKDano. Lauren Segal is a freelance photographer based in Seattle.Edited by Lesley Suter

Evaluation :

5/5