Mardin: A Timeless Gem of Turkey

Donkeys casually wander through the city’s winding alleys, passing beneath low arches and doorways, their sudden braying around corners startling visitors, while locals carry on with their day, unfazed by the noise.

The air is filled with the soft murmur of multiple languages—Arabic, Syriac, Armenian, Kurdish, Torani, Turkish, and Aramaic, the ancient tongue once spoken by Jesus—echoing off the weathered stone walls.

This is Mardin, a historic city in southeastern Turkey where centuries of heritage greet you at every turn.

From above, Mardin’s gleaming white and golden buildings cascade down the hillside, offering a view across the plains toward modern-day Syria. Long ago, this city was part of Mesopotamia, the fertile land nestled between the Euphrates and Tigris rivers.

Mardin sits at the crossroads of ancient civilizations like the Sumerians and Babylonians, with a rich and layered history.

A city that has passed through many hands over the centuries.

Throughout its long history, nearly every great empire has claimed a stake in Mardin. From 150 B.C.E. to 250 C.E., the Nabataean Arabs called it home, only for it to become a key Syriac Christian hub by the 4th century, founded by the Assyrians. Then the Romans and Byzantines followed.

In the 11th century, the Seljuk Turks sought to claim Mardin, only to be challenged by the arrival of the Artuqid Turkomans in the 12th century.

Originating from northern Iraq (modern-day Diyarbakır, Turkey), the Artuqid dynasty held power in Mardin for 300 years, until the Mongols took over, only to be replaced later by a Persian Turkoman monarchy.

Remarkably, when Ottoman Sultan Selim the Grim conquered Mardin in 1517, a Christian community still thrived in the town. Today, Mardin’s unique atmosphere reflects this rich tapestry of diverse ethnic and religious influences.

Despite its ancient history, Mardin remains a vibrant and thriving town where the past continues to shape the present.

One of the city’s historic landmarks, Kırklar Kilisesi, also known as Mor Behnam, is a Syriac Orthodox church dating back to 569 C.E. The Church of the Forty Martyrs, as it’s known in English, was named after the relics of 40 martyrs brought here in 1170.

The church's design is an embodiment of simplicity. A graceful, domed bell tower with a cross crowns a rectangular courtyard enclosed by golden stone walls. Inside, services are held regularly, continuing an unbroken tradition of Aramaic Christians that has endured for over 700 years.

Queen of Snakes

Just a few streets away, the Mardin Protestant Church, constructed by American missionaries over 150 years ago, has reopened with an active congregation after nearly six decades of closure. Meanwhile, shop windows are adorned with vibrant depictions of the Shahmaran.

The Shahmaran, a mythical figure that is part snake, part woman, takes its name from Persian: 'Shah' meaning queen, and 'mar' meaning snake. According to Anatolian folklore, she once lived in Mardin.

The Abdullatif Mosque, dating back to 1371, features elaborate decorations that stand in striking contrast to the stark simplicity of the region’s churches.

The two grand portals are so finely carved that it’s almost unbelievable they are made from solid stone. The centerpiece is a recessed stalactite carving, surrounded by intricate vertical and horizontal stone patterns.

The mosque is an exquisite example of Artuqid-era architecture, while the Zinciriye Medresesi, a religious school built in 1385, is another masterpiece. The seminary, also known as İsa Bey Medresesi after the last Artuqid Sultan, boasts a grand doorway with remarkable masonry, and the ribbed stone domes atop the roof seem almost weightless. Beautiful gardens lead to a small mosque with an intricately carved mihrab niche that marks the direction of Mecca.

The post office is also worth visiting. It was converted for public use in the 1950s and drew attention from domestic tourists in the early 2000s when it became the filming location for the popular Turkish TV series 'Sıla.'

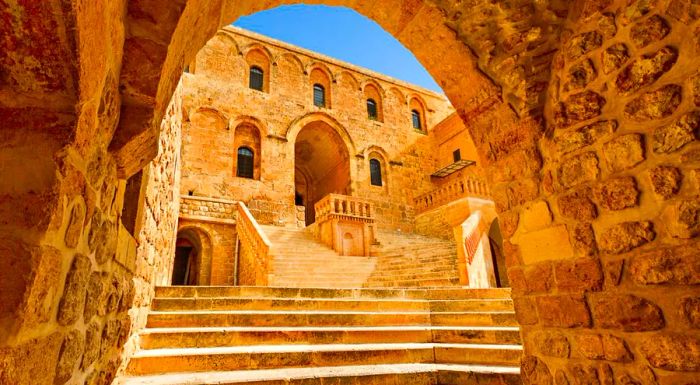

Originally designed as a private residence by Armenian architect Sarkis Elyas Lole in 1890, the building features steps leading through a small archway to a magnificent terrace, offering sweeping views of the Şehidiye Mosque and the vast plains beyond.

Lole is also credited with designing the 1889 cavalry barracks, now home to the Sakıp Sabancı Mardin City Museum. The museum’s exhibits include lifelike scenes and contemporary displays, offering a vivid portrayal of life in Mardin, both past and present.

At the Mardin Museum, housed in the former Assyrian Catholic Patriarchate built in 1895, ancient history comes to life through an impressive collection of Mesopotamian and Assyrian artifacts, Roman mosaics, and Ottoman-era objects.

Underground sanctuary

No matter which direction you walk, Mardin’s streets are filled with stunning sights, with none more impressive than Ulu Camii, the Great Mosque. Though founded by the Seljuk Turks, its present appearance is largely the work of Artuqid ruler Beg II Ghazi II.

In 1176, he initiated a series of renovations, with additional work completed later by the Ottomans in the 18th and 19th centuries.

The surface of the mosque’s lone remaining minaret is adorned with intricate inscriptions from the Seljuks, Artuqids, and Ottomans. This passion for craftsmanship is echoed in the delicate silver filigree jewelry known as tel kare, sold in many local shops, though most of it is crafted in family-run workshops in nearby Midyat.

A short drive from the city, the solemn yet awe-inspiring Deyrulzafaran Monastery (House of Saffron), the original seat of the Syriac Orthodox Patriarchate, is a must-visit. This expansive, walled complex was built on a site that once served as a sanctuary for sun worshippers.

Despite being destroyed by the Persians and later looted by the 14th-century Mongol-Turkic conqueror Tamerlane, the original underground sanctuary still stands intact.

Guided tours lead visitors through intricately carved wooden doors that are over 300 years old, past ancient Syriac inscriptions, wooden litters and thrones, hand-embroidered scenes from the Bible, and other religious artifacts. Simple guest rooms provide accommodation for those attending services conducted in Aramaic.

Meanwhile, excavations at Dara, a significant Eastern Roman military city about 19 miles from Mardin, have been ongoing since 1986.

The discoveries have been plentiful, with the latest find being an olive oil workshop from the 6th century. This discovery affirms Dara’s role as a key center for olive oil production and trade, as well as a site of numerous military confrontations.

Many of the ancient cisterns from Mesopotamia’s original irrigation system are now accessible to the public. One of them, so vast that locals call it zindan (the dungeon), is said to have been used as a prison. It plunges 82 feet underground, with entry through the basement of a village house—if you can find the man with the key.

In Mardin, another ancient site of interest is the castle. During the Roman era, the city was known as Marida, a Neo-Aramaic term meaning 'fortress.'

The fortress sits high above the town, with a path that nearly reaches its gates. However, it's not accessible to the public. For some, the climb (and the potential risk of heatstroke in summer) may be worth it for the breathtaking panoramic views.

Others might prefer to relax in town with a glass of wine. The majority of local winemakers are Assyrians, who maintain ancient traditions and use regional grapes to craft wines that are distinct from those found elsewhere in Turkey. It's a perfect way to celebrate Mardin's rich cultural diversity.

1

2

3

4

5

Evaluation :

5/5