Martha’s Vineyard Was Once a Sanctuary for the Deaf. I Took a Journey to See If It Still Holds True.

Just days before my trip to Martha’s Vineyard, my hearing aids broke. As a deaf person who primarily uses American Sign Language (ASL), my hearing aids serve more as a visual signal of my deafness to others than a tool for understanding sound. Without them, hearing people often think I’m ignoring them, and impatience quickly turns to frustration. I’ve faced shouts in stores, shoves on sidewalks, and even assault for not responding fast enough to hearing individuals.

With a mix of nervousness and excitement, I began my journey without my hearing aids.

Traveling alone as a deaf person to a new place brings its own risks. But it was early May, and the trip offered a much-needed break after a busy semester of teaching, editing my book, and taking care of two young boys. I’ve always appreciated solo travel for how it allows me to experience a place in my natural state of silence. This time, it felt especially fitting—I was going to test Martha’s Vineyard’s reputation as a safe space for the deaf.

Before setting out, I devoured all I could about the island’s deaf history, from Nora Groce’s well-known book Everyone Here Spoke Sign Language to academic papers by deaf historians. I mapped out my route, checked travel sites, and planned the journey from Philadelphia to the Vineyard. In my pre-kids days, I loved the long journeys—like taking a train to Montreal or driving through Newfoundland. But now, with only three days before returning to work and parenting duties, I rented a car, packed a bag, dropped my boys at school, and headed north.

A history treasured by a few, but unknown to many.

The history of sign language on Martha’s Vineyard dates back to the late 1600s when Jonathan Lambert, a deaf man, and his family joined a group of Massachusetts Bay colonists to settle on the island. The island's isolation contributed to hereditary deafness over the following centuries, peaking in the 1850s when 1 in 155 islanders, and 1 in 25 in Chilmark, were deaf, compared to 1 in 5,700 on the mainland.

This led to the creation of Martha’s Vineyard Sign Language (MVSL), a unique sign language used by both deaf and hearing islanders. MVSL allowed deaf people to fully integrate into the island’s work and social life, without prejudice. Deaf residents held diverse roles, from fishermen to business owners—Jared Mayhew, a deaf landowner, even founded the island’s first bank. The island’s deaf community thrived until better transportation and the establishment of a residential school for the deaf in Hartford, Connecticut, in 1817 began to pull islanders away, eventually leading to the decline of MVSL. This history was later documented in Nora Groce’s famous book.

The reality surrounding this issue is quite complex. Groce’s research took place over a century after the deaf community had diminished, and Martha’s Vineyard Sign Language (MVSL) was eventually absorbed into American Sign Language (ASL) as we know it today. Deaf historians in the UK have largely dismissed Groce’s ideas regarding the genetic and linguistic origins of hereditary deafness and his claims that MVSL originated in Kent, England. While compiling family histories on the Vineyard, Groce failed to distinguish between genetic and acquired deafness; this oversight, combined with the use of pseudonyms in his book, complicates efforts to trace familial connections in contemporary times. Recent studies of island genealogy, marriage, and migration patterns indicate that the deaf community on the island emerged later and had ties to the Hartford deaf community and ASL earlier than previously assumed.

A distinct language known as Chilmark Sign, or Martha’s Vineyard Sign Language (MVSL), evolved and was utilized by both deaf and hearing residents of the island.

What is clear is that for many generations, a relatively large number of deaf individuals inhabited Martha’s Vineyard, communicating using a signed language characterized by unique vocabulary and grammatical structures, including a two-handed alphabet. This language was likely developed organically by deaf islanders rather than being introduced from elsewhere.

It is improbable that every resident of Martha’s Vineyard was fluent in sign language. While it’s likely that many people in Chilmark were, given the average family size, it’s reasonable to assume that most families had at least one deaf member. The phenomenon of sign language being used widely in communities with multiple large deaf families has been documented in other locations, including Lantz Mill, Virginia, during the same era, and in various places worldwide today.

Nevertheless, the island’s geographical isolation suggests that even if hearing residents were not proficient in sign language, their regular interactions with deaf individuals would minimize the impact of ableism. Unlike the perception of deafness as a disadvantage in today’s society, hearing islanders interviewed by Groce showed respect for their deaf neighbors, viewing their deafness as just one aspect of their personalities and abilities. In the context of a 19th-century fishing economy, having some knowledge of sign language would have been beneficial for communication between boats and the shore, especially when shouting into the strong winds was not a viable option.

While the idea of Martha’s Vineyard as a deaf paradise is partially a fantasy, it’s difficult to abandon such a captivating myth. In the United States today, only around 8 percent of parents with deaf children learn enough American Sign Language (ASL) to hold a meaningful conversation with them—leaving us yearning for a utopia, and Martha’s Vineyard stands as a semblance of an ancestral homeland for many.

With the legend of the island in my heart and the spirits of my ancestors guiding me, I found myself on the deck of a Steamship Authority ferry, traveling between Falmouth, Massachusetts, and the island's port at Vineyard Haven on a dreary afternoon. Moments after we set sail, the Island Home was shrouded in a thick fog, rendering everything ahead invisible. The cold air made me ponder what had motivated the Massachusetts Bay settlers, or the Wampanoag before them, to navigate into such a dense and daunting unknown.

As I continued on the island's deaf-history tour...

About 40 minutes later, we arrived at Vineyard Haven. I drove over to Edgartown, where I’d be staying at the boutique hotel called Faraway (see How to take this trip, below), so I could leave my car behind. I strolled through the town in a carefree manner, indulging in fudge, browsing through upscale island attire, and pondering which ice cream shop was the most enticing. I admired the charming wood-shingled buildings and bright white churches, read the numerous plaques and signs on noteworthy historical structures, and lingered in Edgartown Books. I spent a significant amount of time at the dock, soaking in the salty air and shimmering waters of the harbor.

After dinner, I turned in early. My trip was centered around the Martha’s Vineyard Chamber of Commerce’s driving tour map, which highlighted key historical sites related to the deaf community, and I intended to make all ten stops the following day. From my hotel balcony, I watched the sun dip below the horizon and the fog creep back in. Below me, fire pits by the pool flickered to life in neat rows, reminiscent of the signal fires that must have once blazed along these shores centuries ago. I drifted off to sleep filled with anticipation, as if my journey was only just beginning.

The driving tour map is a relatively recent addition; while the deaf history of the Vineyard has been cherished by the deaf community for ages, it was largely overlooked by the wider public until now.

In the morning, I returned to my car, map in hand, brimming with a spirit of adventure. This map is relatively new; although the Vineyard’s deaf history has long been valued by the deaf community, it has only recently begun to gain recognition from the public. This renewed interest is partly due to the work of islander Lynn Thorp, who, after reading Groce’s book, became fascinated by how signed language could enhance the lives of her hard-of-hearing husband and friends. Determined to improve access to ASL resources on the island, she dedicated over a decade to airing mini-lessons on public access TV and creating DVDs for local libraries. In 2020, she shifted her focus to promoting the island’s history to visitors, collaborating with the Chamber of Commerce to include deaf-centric materials on their website, including the driving map.

Cell service was reliable, but Google often failed to distinguish between private and public roads, leading to many U-turns. I began my tour in Vineyard Haven and visited the Martha’s Vineyard Museum ($18 for off-islanders, closed on Mondays). During the 2023 season, the museum featured a temporary exhibition titled They Were Heard, which highlighted the island’s deaf history, but much of it has since been stored away and returned to the archives.

“If a tour group wishes to view some of the artifacts, I can arrange a special session here in the library,” stated museum historian Bow Van Riper, who led the research for the exhibit. He recommended that groups reach out to the museum a few weeks ahead of time to make their requests.

Courtesy of Martha’s Vineyard Museum

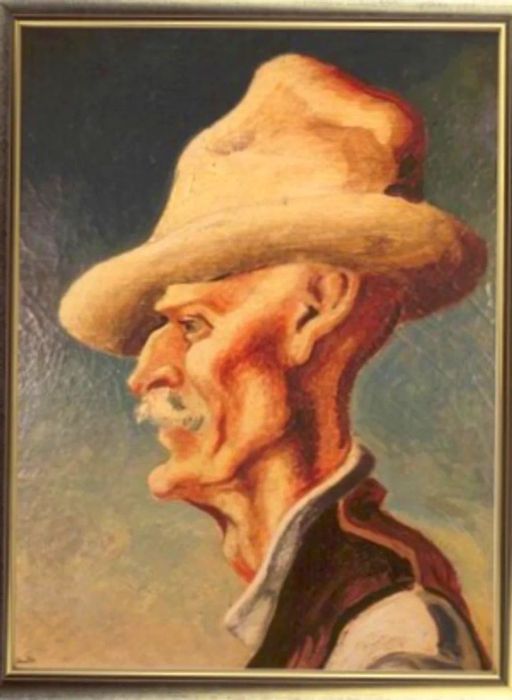

Visitors who arrive alone or without prior notice can view two significant pieces of Vineyard deaf history in the permanent collection: a transcript of an interview with Mildred Huntington, a hearing woman who was babysat by a deaf islander (they can also listen to the audio), and a 1926 painting by renowned American artist Thomas Hart Benton of his deaf neighbor, a Chilmark farmer named Josie West.

After visiting the museum, I made my way to West Tisbury, to the cove where the Lambert family had settled. Lambert’s Cove, a delightful blend of wooded areas and sandy beach, was the tour stop that most resembled a classic New England beach getaway. It was one of the few places where I encountered other travelers—some hiking and others lounging on towels near the water. The scenic ocean views and dogs playing fetch in the surf felt both charming and familiar, making it hard to envision what life was like when the Lamberts first arrived. I continued on, veering inland toward tour stops 4 through 10 in Chilmark.

As I ventured inland, I was struck by the vastness of the farmland—expansive and vibrant, often marked by centuries-old fieldstone walls. This beauty led me to reflect on the privilege of preservation. My understanding of island life was shaped by the contrasting landscapes of my childhood: the bustling Jersey Shore and the serene rural coastline of Croatia. In New Jersey, every inch of the busy shore is claimed and developed for profit, while in Croatia, I experienced the tranquil postwar charm of a fishing village, devoid of shops or telecommunications, where the stunning seascape remains untouched and uncommercialized.

Photo by Sara Novic

The Vineyard’s expansive farms and stables, coupled with the choice to keep certain wooded areas undeveloped, likely reflect a legacy of inherited wealth that allows owners to prioritize preservation over profit from summer tourism. Yet, it was apparent that the island's deaf history is preserved in a fragmented manner. At Abel’s Hill Cemetery, where at least 28 members of the Chilmark deaf community are interred, there is no map to guide visitors to historically significant figures. Similarly, places like Lambert’s Cove, Squibnocket Beach, and Menemsha Harbor lack informative resources detailing the origins of MVSL, which is believed to have emerged from the experiences of Lambert and other deaf fishermen.

Unsurprisingly, the core of the island’s deaf history can be found at the Chilmark library. Ebba Hierta, the library director, graciously sat down with me on short notice to discuss the library’s history and its connection to what she referred to as “the deaf ancestors.” These ties were both figurative and literal—one of the library’s rooms was once home to a notable deaf couple, Benjamin and Katie West. Benjamin was a lifelong resident of the island, while Katie, originally from Rhode Island, married into the local culture. Believed to be the last fluent signer of MVSL, Katie passed away in the early 1950s. The town later acquired the Wests’ house, transforming it into the Chilmark library. Over the years, several additions have been made, and the original room now features a small shrine of printouts and a DVD recording (notably without subtitles) about MVSL and the Chilmark deaf community. Additionally, the library’s website offers more resources, including a teaching guide and a recorded presentation on deaf history, complete with ASL interpretation.

Photo by Ebba Hierta

“During the summer, we see many visitors at the library, including quite a few who are deaf, but not exclusively,” Hierta noted. Among local residents, library and museum programs have heightened awareness of the historical deaf community. “I wish we could do more,” she expressed, “but it’s challenging without a larger research staff and budget.” The library encourages visitors wishing to speak with a librarian to make an appointment at least a week in advance, especially during peak season. As I was leaving, Hierta took me to the children’s section, where a mural high on the wall depicted children playing in an attic, engrossed in a sign language book, one child signing the letter ‘L’—a static gesture of the sign for ‘library’—captured in time.

As I approached the end of my tour at Squibnocket Beach, a sense of nostalgia washed over me. Likely serving as a launching point for deaf fishermen, I imagined how this now quiet shore might have once been alive with boats, nets, and the lively exchanges of sign language. The stunning vistas made it easy to reflect on finality. Today, deaf culture faces increasing challenges as medical advancements like gene therapy and stem cell treatments aim to eliminate deafness. Gazing at the clear horizon, I pondered whether the deaf community here had sensed a similar existential threat as their numbers declined over the years, or if the sign language skills of their hearing neighbors had provided some reassurance against their fears.

Photo by flyben24/Shutterstock

The future of deaf-history tourism on Martha’s Vineyard

Although glimpses of Vineyard's deaf history can be found easily if you know where to look, true access to cultural information demands significant preparation in advance (and a reliable internet connection).

I hope that initiatives to honor this rich history will persist, especially through subtle means like plaques or materials that tourists or passersby might stumble upon, just as deaf and hearing Vineyard residents once interacted casually in their daily lives.

More of this may be coming soon. Following Hierta’s suggestion, I reached out to the leader of Clemson University’s Martha’s Vineyard Sign Language Project, which aims to benefit residents, merchants, and tourists alike. Jody Cripps, assistant professor of American Sign Language in the Department of Languages, explained that the team has a comprehensive mission involving preservation, research, and development, and is collaborating with islanders to determine the best ways to commemorate, memorialize, and disseminate information. “We considered plaques,” Cripps noted, “but we want to ensure that our efforts aren’t solely aimed at busloads of tourists. We also wish to show respect for those who call Chilmark home.”

Cripps mentioned that the team was developing a cemetery map that would mark the locations of historic deaf community members’ graves, which he ultimately envisioned as a document available for people to pick up at the library. However, finding these graves is a challenging task, and he was uncertain when it would be completed.

Although deafness is no longer at the heart of Vineyard culture, its spiritual legacy continues to be significant.

In the meantime, even though deafness is no longer a focal point of Vineyard culture, its spiritual legacy is still evident. While traveling, I often encounter individuals who become anxious at the mention of deafness, but during my days on Martha’s Vineyard, no one seemed perturbed. A diverse range of people across the island—from the concierge and librarian to Steamship Authority terminal staff—were willing to switch to writing when needed. Waitstaff at Espresso Love and Atlantic effortlessly took my orders by pointing at the menu. A cashier at Rosewater Market gestured so fluidly that I found myself surprised by our interaction. The general manager at the Faraway hotel demonstrated the manual alphabet, spelling out simple words as we crossed paths; a parking attendant signed “thank you” as I paid.

Perhaps these seamless interactions were due to the islanders’ heightened awareness of their history, fostered by community programs led by libraries and individuals like Thorp. Maybe the tourist economy has trained people to be courteous, both to the deaf individuals who visit Chilmark and across different language barriers. Or perhaps it was merely coincidence. Or maybe it was my own mindset; I approached each encounter with newfound confidence, buoyed by the realization that I was standing on the land of our deaf ancestors, and a part of me truly belonged there.

On Martha’s Vineyard, no one communicated in sign exactly, yet nobody viewed me as out of the ordinary. And whether or not the majority of hearing islanders were familiar with MVSL centuries ago, I believe it was the acceptance of deaf individuals that made the place truly unique; in this respect, its legacy endures.

How to embark on this journey

Photo by Matt Kisiday

Where to stay: My primary accommodation was Faraway, a boutique hotel located in Edgartown that masterfully combines historic allure with luxury features, a hallmark of Vineyard hospitality. My room, a studio suite in a separate building, boasted a breathtaking view of the bay and Chappaquiddick Island. Faraway offers a restaurant and a large pool area with food service, but its prime location at the edge of Edgartown’s main shopping and dining area is arguably its most significant advantage. In the opposite direction, it’s just a 15-minute walk to a sandy public beach and the Edgartown lighthouse.

The tour: The self-guided deaf history driving tour is available online through the Martha’s Vineyard Chamber of Commerce website or can be downloaded as a PDF brochure. The Chilmark Library offers a resource page with additional background information and videos.

Getting around: If my trip to Martha’s Vineyard was focused solely on a beach vacation, then staying at Faraway, exploring Edgartown, and using bicycles along with the public shuttle could easily fulfill my needs. However, having a car on the island—whether rented or brought over by ferry—demands careful planning for reservations during the busy season. (Conversely, walk-on ferry travelers can purchase same-day tickets.) Yet, to fully experience the island’s rich deaf heritage, having a car would be essential.

Evaluation :

5/5