MSG, often misunderstood for years, is finally getting the recognition it deserves.

Calvin Eng, the owner of Bonnie’s, a Cantonese-American restaurant in New York, proudly expresses his fondness for monosodium glutamate.

In fact, he has the letters 'MSG' inked on his arm, and his menu features a signature cocktail known as the MSG Martini.

“MSG makes everything taste better, whether it’s Western dishes or Cantonese classics,” Eng shares with Dinogo.

“We put it in drinks, desserts, and savory dishes. It’s in almost everything. Salt, sugar, and MSG— I like to call them the Chinese Trinity of seasonings,” he adds.

Admitting to using MSG, once a surefire way to turn customers away, hasn't hurt Bonnie's popularity. In fact, since its debut in Williamsburg, Brooklyn in late 2021, the restaurant has become one of the most sought-after spots in New York, earning multiple 'Best New Restaurant' accolades from top media.

Eng was honored as one of Food & Wine Magazine's Best New Chefs of 2022 and made the 2023 Forbes 30 Under 30 list, among other recent achievements.

Breaking the MSG Myth: 'It was once considered a forbidden ingredient.'

Eng joins a growing group of renowned chefs, including David Chang of Momofuku and author/chef Eddie Huang, who are championing MSG and working to lift the stigma surrounding this century-old ingredient.

“When I was growing up, using MSG was a definite no-no,” Eng recalls.

“My mom would never use MSG, but she’d often rely on chicken powder in her cooking. As a kid, I didn’t realize they were essentially the same thing until I grew old enough to understand,” Eng reflects.

Here’s a brief look at MSG's origins:

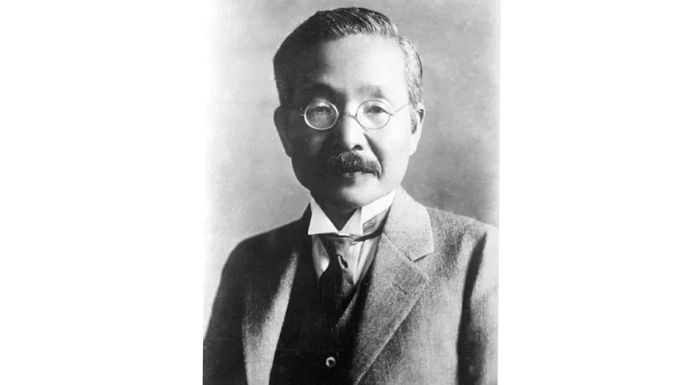

In 1907, Kikunae Ikeda, a Japanese chemist, boiled down a large amount of kombu seaweed to extract glutamate, a substance responsible for the savory, long-lasting flavor in foods like dashi broth.

Ikeda coined the term 'umami' and then refined the substance into MSG, which, when crystallized, can be used just like salt or sugar.

The following year, businessman Saburosuke Suzuki gained a partial patent for MSG and, alongside Ikeda, founded Ajinomoto, a company dedicated to producing the seasoning.

MSG quickly became a groundbreaking invention, winning awards and becoming a beloved kitchen staple, especially among middle-class homemakers in Japan.

Over the following decades, MSG gained worldwide recognition and popularity.

After World War II, the US military even hosted the first-ever MSG symposium to explore how the seasoning could improve the taste of field rations and enhance soldiers' morale.

However, MSG's reputation began to decline in 1968, after a US doctor published a letter in a medical journal titled 'Chinese Restaurant Syndrome.'

In the letter, the doctor outlined symptoms such as 'numbness at the back of the neck,' 'general weakness,' and 'palpitations.' He speculated that MSG, along with ingredients like cooking wine and high sodium levels, could be responsible for these reactions.

MSG bore the brunt of the backlash, with the consequences of that letter echoing across the globe for decades.

Restaurants publicly distanced themselves from MSG. PR teams for food and beverage brands dreaded being asked about it. Diners who felt unwell after eating blamed it on MSG.

What exactly is in MSG?

“Many people don’t realize that MSG is derived from plants,” explains Tia Rains, a nutrition scientist from Chicago and vice president of customer engagement and strategic development at Ajinomoto.

“Our MSG production process involves fermentation, which is similar to how beer or yogurt is made,” she adds.

To create MSG, plants like sugarcane or corn, which are rich in sugar, undergo fermentation with microbes to produce glutamate—an amino acid found in foods, produced by our bodies, and functioning as a neurotransmitter.

Next, sodium is added, and the glutamate crystallizes, transforming into the salt-like MSG we recognize in stores and kitchens today.

“As a scientist, I find how MSG works one of the most fascinating aspects of food science,” says Rains.

“We have different receptors on our tongue for different tastes. The receptor for umami, when viewed under a microscope, resembles a Venus Flytrap,” she explains, forming a 'C' shape with her hand.

“Glutamate is the amino acid that perfectly fits into that receptor,” she adds.

So, what exactly is umami? In recent years, it has been recognized as the fifth taste, joining sweet, sour, salty, and bitter, and is often described as savory.

When glutamate binds to the receptor, it triggers the umami flavor sensation on our taste buds. If the food contains one of two nucleotides – inosinate or guanylate – the glutamate can remain attached to the receptor longer, enhancing the flavor.

“In simple terms, if you want to create an umami explosion, combine glutamate – the key to umami – with one of these nucleotides (inosinate or guanylate). It’s like sending multiple umami signals to your brain,” Rains explains.

It sounds complex, but you’ve likely been working with glutamate, inosinate, and guanylate in your cooking without even realizing it.

Carrots and onions, rich in glutamate, enhance the umami flavor of beef, which is high in inosinate. Similarly, bonito fish (inosinate) and kombu seaweed (glutamate) work together to create a robust umami taste.

Foods like tomatoes and cheese are also natural sources of glutamate.

“When people tell me they ate at a Chinese restaurant and experienced breathing difficulties or chest tightness, I worry,” says Rains. “I’d tell them, ‘You need to follow up on that because MSG isn’t an allergen. It won’t cause an allergic reaction. Our bodies naturally produce glutamate, so it’s not possible to be allergic to it.’”

Despite persistent claims of negative reactions to MSG, decades of scientific studies have not confirmed MSG sensitivity. Global health organizations, including the US FDA, have declared MSG safe for consumption, with the FDA listing it as 'generally recognized as safe' (GRAS).

“Although many people claim sensitivity to MSG, studies involving individuals who believe they are sensitive, where they are given either MSG or a placebo, have not been able to consistently trigger any reactions,” according to the FDA’s website.

The Centre for Food Safety in Hong Kong highlights that using MSG can help lower sodium intake, which is linked to health issues like high blood pressure, heart disease, and stroke.

“When combined with a small amount of salt during cooking, MSG has been shown to reduce the total sodium content in a dish by 20 to 40%,” according to a food safety assessment conducted by a scientific officer from the Hong Kong government.

Changing perceptions

Despite ongoing negative opinions surrounding MSG, Ajinomoto’s marketing team remains hard at work, striving to shift public perceptions.

“Even after all these years, we haven’t made significant progress in reducing sodium levels in the food supply, at least not in the US,” says Rains.

“We have a tool that can help product developers reduce sodium, yet we’re not utilizing it due to outdated, xenophobic, and often racist misconceptions about an ingredient that has been safely consumed for over a century. It was a challenge too important to ignore.”

In 2020, Ajinomoto’s team succeeded in convincing Merriam-Webster to revise the definition of 'Chinese Restaurant Syndrome' in its dictionary and has since organized symposiums to educate the public about MSG and umami.

Ajinomoto’s oldest factory in Kawasaki now boasts a visitor center where visitors can view the original crystals of MSG created by Ikeda over a century ago, along with exhibits showcasing the history and production process of MSG.

The tour, primarily conducted in Japanese, is open to the public and free of charge. Visitors, typically schoolchildren, have the chance to bottle their own MSG keychains and shave bonito flakes to get a hands-on experience of umami.

Next, they explore the vast 370,000-square-foot facility on a panda bus, named after the company’s mascot, Ajipanda, while friendly staff wave them off as they depart.

Bonnie’s most popular dish: Cha siu bkrib (with MSG)

Today, chefs like Eng are no longer shy about discussing MSG or listing it on their menus, playing a crucial role in changing outdated attitudes toward the ingredient.

“I believe our clientele is younger, more informed about MSG, and not afraid to enjoy it,” he says.

“We’re proud to use it and help shift the negative perception surrounding it,” he adds.

Aside from health concerns, some customers view MSG as a shortcut – a quick flavor boost. Eng disagrees with this view, pointing out that their dishes are still made with traditional methods.

“We still make our stocks and broths the old-fashioned way, simmering bones for hours. We just use a small amount of MSG to season, which is different from simply adding MSG to hot water and serving it with noodles,” he explains.

Many of Bonnie’s offerings are reimagined Cantonese classics with both playful and meticulous twists.

For example, the cha siu bkrib sandwich was inspired by two dishes – the iconic McDonald’s McRib sandwich and a traditional Cantonese dish of black bean ribs that Eng’s mother, Bonnie, loves to prepare.

To create the sandwich, Eng steams the ribs until the bones separate easily from the meat. The deboned meat is then marinated overnight in a house-made charsiu sauce, which includes hoisin, maltose, fermented red soy curd, MSG, and other ingredients.

Once the meat is prepared, it’s pressed and flattened for several hours before being glazed and roasted in the oven.

Finally, Eng assembles a generous portion of the rib meat, onions, pickles, and mustard on a Cantonese ‘zyu zai’ bun, a soft, traditional bun from his mom’s favorite bakery in Chinatown.

Since Bonnie’s opened, this dish has remained the most popular item on the menu.

“From the start, our goal has been to show people what Cantonese food is and what it can be – always fun, playful, and easy to enjoy,” says Eng.

Although attitudes toward MSG may be gradually shifting in the United States, this change has not been mirrored in other parts of the world.

“Depending on where you are, the perception of MSG can be either highly negative or quite positive,” says Rains.

Rains hopes that as MSG's reputation improves in the US, it will inspire change in places where the ingredient is still seen as taboo.

“The negative perception of MSG began right here in the United States,” Rains explains.

“It’s not unreasonable to believe that if we can make progress here in the US, educate people, and help them understand the ingredient, it could have a ripple effect globally in the future.”

1

2

3

4

5

Evaluation :

5/5