Researchers have made an astonishing find: the first ever pregnant Egyptian mummy, which has left the scientific community in awe.

An Egyptian mummy once thought to be a priest has now been identified as a pregnant woman, a groundbreaking discovery that challenges previous assumptions.

This world-first discovery was made by Polish researchers as part of the ongoing Warsaw Mummy Project, a major archaeological endeavor.

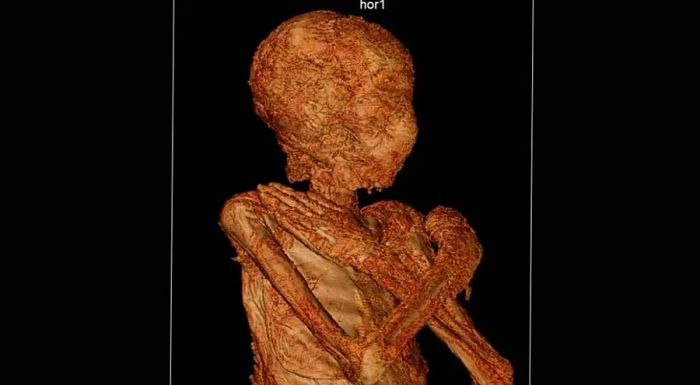

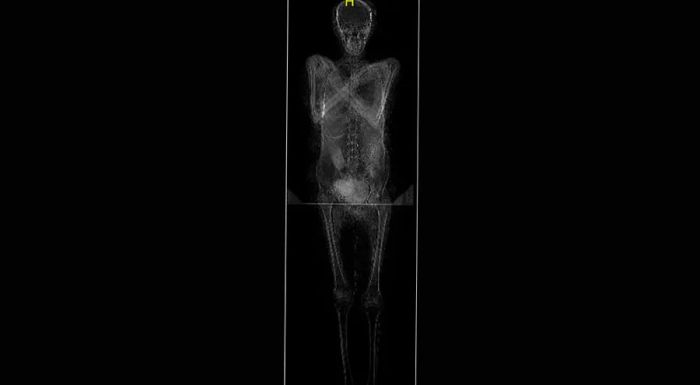

The team, dedicated to examining mummies from Ancient Egypt since 2015 at the National Museum in Warsaw, uncovered the mummy's true identity when a scan revealed the outline of a tiny foot within her abdomen.

Marzena Ożarek-Szilke, an anthropologist and archaeologist from the University of Warsaw, mentioned that her team had already prepared their research findings and were ready to submit them for publication.

She shared with the Polish state news agency PAP: 'Together with my husband Stanisław, an Egyptologist, we reviewed the scans one last time and spotted something unmistakable—a small foot, something all parents of young children would recognize, inside the deceased woman's abdomen.'

Wojtek Ejsmond, one of the founding members of the Warsaw Mummy Project, told Dinogo that the mummy was brought to Poland in 1826 by Jan Wężyk-Rudzki.

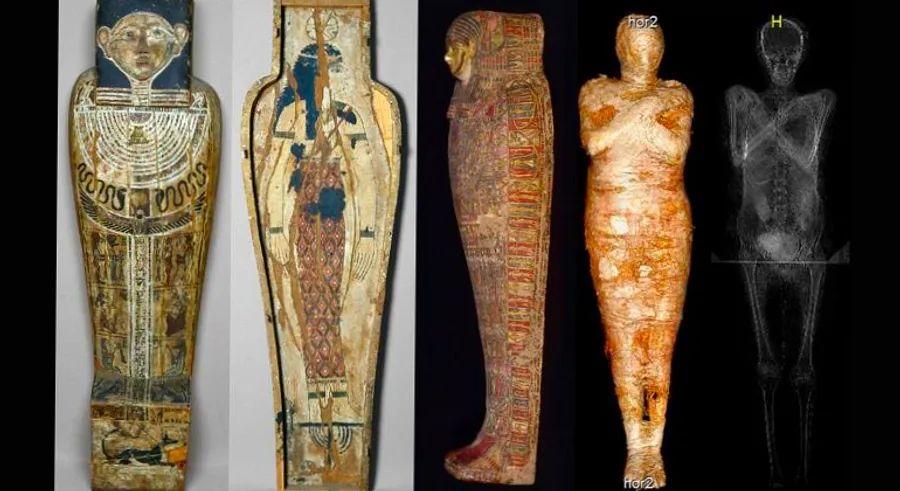

At first, the mummy was thought to be a woman, but by the 1920s, a translation of an inscription on the sarcophagus revealed the name of an Egyptian priest, Hor-Djehuty. The mummy, belonging to the University of Warsaw, has been displayed at the museum since 1917, on loan from the university.

Through their research, the team uncovered some intriguing findings. By using computer tomography, which allowed them to examine the mummy without removing its bandages, they discovered the body had a fragile skeletal structure. Further analysis confirmed the body was female, as there were no signs of male anatomy. A 3D scan also revealed the presence of long, curly hair and mummified breasts, according to the researchers.

Additional investigations into the mummy's condition revealed further details.

Ejsmond informed Dinogo that the woman likely died between the ages of 20 and 30, and the fetus she carried was estimated to be 26 to 30 weeks gestation.

'The cause of death remains unknown and will be the focus of future studies,' Ejsmond commented.

One of the key questions for the researchers is why the fetus—whose gender remains undetermined—was not removed, considering internal organs were routinely extracted during the mummification process.

Ejsmond remarked, 'This discovery raised the question of why the fetus was not removed. We can't say for sure, but it could have been due to religious beliefs, a notion that the unborn child lacked a soul, or perhaps because extracting the fetus at such a late stage could have caused irreversible damage.'

When Wężyk-Rudzki first brought the mummy to Poland in the 19th century, he claimed it was discovered in the Royal tombs of Thebes.

However, the archaeologists remain uncertain about the mummy’s true origins and background.

Ejsmond clarified, 'We can't be sure if this claim is accurate. It was not uncommon for individuals to fabricate provenance in order to increase an artifact's value and importance. We must approach such claims with caution, as there's no evidence to support them.'

This might help explain why the mummy was placed in a tomb bearing the name of a priest.

Ejsmond commented, 'This is one of the most complicated issues we face. We know that in ancient times, coffins were often reused. Tombs were sometimes looted, and the stolen coffins were repurposed for new burials.'

'In the 18th and 19th centuries, tomb robbers frequently raided mummies’ tombs, and antiquities dealers would steal valuable artifacts, replacing the bodies with others,' Ejsmond added.

Ejsmond estimates that about 10% of the mummies held in museum collections may actually be housed in incorrect coffins.

The research team, currently studying a collection of approximately 40 human and animal mummies, plans to take micro-samples from the body to determine the cause of death.

Their research has been published in the Journal of Archaeological Science.

1

2

3

4

5

Evaluation :

5/5