The man on a distant island preserving Napoleon’s legacy

Nestled in the heart of the Atlantic Ocean, St. Helena sits between South America and Africa.

Located 1,200 miles west of Windhoek, Namibia, this isolated 46-square-mile island features stunning cliffside trails, breathtaking scenic drives, and fields of flax swaying in the winds stirred by the surrounding ocean.

With fewer than 5,000 residents, it sometimes seems as if there are more dolphins swimming in the surrounding waters than people living on the island, often referred to as 'Saints'.

Despite its isolation, St. Helena is internationally renowned for being the final resting place of its most famous resident, who passed away there over 200 years ago.

Napoleon Bonaparte, the first emperor of France and a conqueror across much of Europe, passed away at Longwood House on May 5, 1821.

However, Longwood House wasn't his chosen home. After his defeat at the Battle of Waterloo in 1815, Napoleon was exiled to St. Helena. Having escaped a previous exile on Elba, an island off the coast of Italy, the French emperor was seen as a flight risk by European rulers. St. Helena, a remote British colony, lay 5,000 miles away from Europe, requiring a grueling 10-week boat journey.

Napoleon spent more than five years on St. Helena, arriving in October 1815. It was here that he forged his legend, dictated his memoirs, and dealt with the chronic pain of old battle injuries – possibly aggravated by fatal stomach cancer.

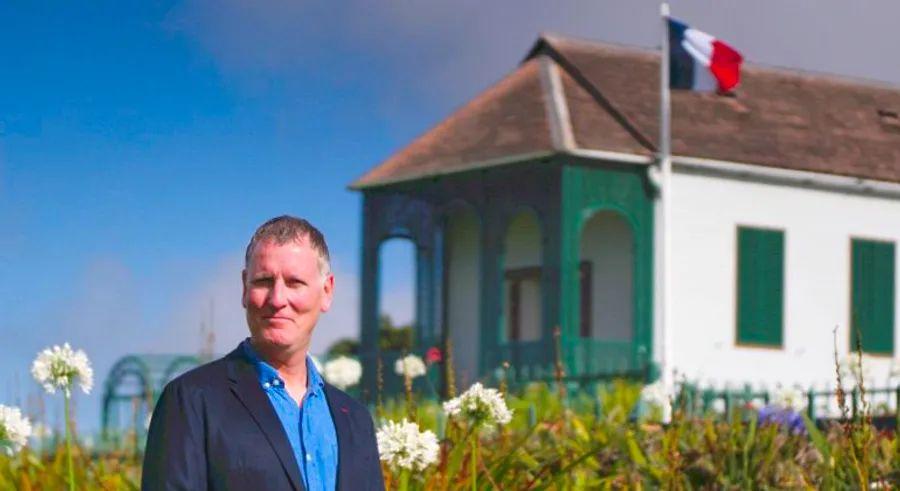

Two centuries later, his legacy still endures on the island, tended to with care by one man: Michel Dancoisne-Martineau.

Michel, now 55, hails from Picardy, France. He first arrived on St. Helena at the age of 18 and has rarely left the island since.

Michel has adapted to a lifestyle that is vastly different from most. He leaves the island just once a year, and when he orders goods from Europe, it takes longer for them to arrive in 2021 than it took for Napoleon to reach St. Helena in 1815.

And if you think he's maintaining this lifestyle as a tribute to Napoleon, you'd be mistaken.

A different kind of legacy.

Bought from the British by Napoleon III, the nephew of the first emperor, the Napoleonic landmarks on St. Helena stand in sharp contrast to those in Paris.

Instead of the iconic Tuileries Gardens in Paris, St. Helena boasts the lush gardens of Longwood House, Napoleon's long-term residence, offering a burst of color on the otherwise barren island.

Rather than the Malmaison chateau, St. Helena is home to the Briars, the quaint cottage where Napoleon began his exile.

And where his tomb at Les Invalides in France is grand, St. Helena holds Napoleon’s original burial site. He was laid to rest on a green hillside here, before France moved his remains 19 years later. Now, only a simple stone slab remains, encircled by black-painted railings.

Michel Dancoisne-Martineau oversees all of these sites. As the director of the French Domains on St. Helena and the honorary French consul, it’s his responsibility to preserve these small Gallic enclaves on an island that remains a British Overseas Territory.

This effort to preserve the sites has also involved extensive restoration. Upon his arrival, Dancoisne-Martineau found that the previous curator had left the buildings to be ravaged by the elements.

“The original display was much more in line with the early days of Napoleon’s exile – he allowed the trees to grow thick around the house, making it even darker than it already was,” explains Dancoisne-Martineau. “That was a deliberate choice, but not an aesthetic one. I suggested we try to recreate the house as it was on the day Napoleon died, on May 5, 1821 – both inside and in the garden.”

Over the years, Dancoisne-Martineau has restored the interior woodwork and paint, while also reviving the gardens Napoleon once adored. “You can now see the birdcage, the Chinese pavilion, the ponds, the grotto, and the sunken paths – it’s a joy to experience,” he says. Indeed, the garden, which Napoleon designed himself once he realized he would remain on the island, has transformed one of St. Helena’s most desolate locations into one of its most beautiful.

The legend of the martyr

However, not everyone is pleased with Dancoisne-Martineau’s restoration efforts. A significant part of the Napoleonic legend is built around the idea that Napoleon endured dreadful living conditions on the island.

“Napoleon capitalized on the harsh, miserable conditions at Longwood and the constant bad weather to paint himself as a martyr,” says Dancoisne-Martineau, pointing out that the emperor deliberately evoked Christ-like imagery in the memoirs he wrote while in exile.

In truth, the situation wasn’t far from that image. Longwood, the house assigned to Napoleon, was considered “the worst place on the island,” according to Dancoisne-Martineau. Situated 500 meters above sea level, it was perpetually shrouded in clouds and battered by trade winds. (This wasn’t why the British chose it for him – they placed him there because it was so isolated, perched on a plateau that was difficult to escape from.)

Napoleon’s exile was arranged so hastily that nothing was prepared for his arrival – even the island's governance had to be transferred from the East India Company to the British crown. For the first two days, Napoleon was confined to the ship that had brought him to St. Helena, docked in the harbor.

After two peaceful months at The Briars, a charming cottage overlooking the island's only major town, Jamestown, the arrival at Longwood was a jarring change for Napoleon.

“Little by little, he began to understand the dreadful conditions – both the harsh weather and the dilapidated state of the house,” says Dancoisne-Martineau.

“The wooden floors were rotting, the roof leaked, water poured through the walls, rats scurried under the floorboards, and a smell of stagnant water lingered beneath their feet – it was a dreadful place to be,” Dancoisne-Martineau recalls.

The year-long construction of an accommodation block for his entourage next door brought constant disruption, creating a ‘noise pollution’ on this remote island.

Although the British promised to build him a new residence, it was only finished the week after his passing.

Today, however, Longwood is a beautifully serene location. So much so, in fact, that some visitors leave comments in the guestbook complaining that it’s just *too* perfect.

Some visitors feel let down that it’s not in a state of disrepair, as that would align better with the tale of the notorious house – they would prefer to see it in ruin rather than meticulously maintained,” he says.

“But my responsibility is to showcase the house of a man who passed away just yesterday. I have nothing left to prove,” he remarks.

The arrival of a legend

Dancoisne-Martineau’s own journey is nearly as captivating as that of the legendary figure he helps to immortalize.

Hailing from the rural region of Picardy in northern France, his path to St. Helena unfolds like the pages of a novel. In 1985, at the age of 18, he became enchanted by the poetry of English poet Lord Byron. After reading a biography of Byron so compelling that it left a deep impression, he immediately wrote to the author.

The author of that biography was none other than Gilbert Martineau – the former curator of the Napoleon sites on St. Helena.

“He invited me to visit for a summer holiday, and at 18, I thought it was the perfect opportunity,” he recalls.

Martineau was in the twilight years of his career. He had already retired, but continued to manage the sites, as the position had been advertised for quite some time with no applicants: “They couldn’t find anyone mad enough to take it,” he explains.

Enter the young Michel.

“I fell in love with the island and knew I had to apply,” he recalls. At the time, he was studying agriculture, but this opportunity allowed him to continue his studies via correspondence while earning money to maintain the Napoleonic landmarks. In other words: “It was a perfect arrangement because I was broke.” He returned to France for his mandatory national service, then signed a three-year contract in December 1987.

Dancoisne-Martineau had been discontent in France: “My own family rejected me, and I was left with a profound emptiness in my life.”

Meanwhile, Gilbert Martineau was struggling with his own sense of dissatisfaction. Scarred by his time in the French Navy during WWII, he had grown “disillusioned with humanity,” Michel explains, and retreated to St. Helena, a place he despised – and yet found comfort in his contempt for it.

But Martineau was a man of old-fashioned values. “He believed that a man without children had wasted his life,” Dancoisne-Martineau recalls. So, two years after they first met, he offered the young man an unexpected proposition: he wanted to adopt him.

“He wanted a child to preserve his legacy and family name, and I was seeking a father figure, so we found common ground, and he adopted me,” he says, matter-of-factly.

“He became the father I never had. I’m deeply proud to be his son – we had a typical father-son bond for a decade.”

Thus, Michel Dancoisne, the agriculture student, transformed into Michel Dancoisne-Martineau, the director of the French Domains of St. Helena and an honorary French consul.

His three-year contract was renewed multiple times as he acquired property, built his own home, and eventually married a local woman from St. Helena.

He took care of Gilbert Martineau until the older man fell ill with cancer, prompting their move to La Rochelle, France, for treatment. But after his adopted father passed away in 1995, Dancoisne-Martineau returned immediately to St. Helena.

He has never left the island.

The ‘Frenchman’

Today, known as “the Frenchman” among the locals, he is one of St. Helena’s most iconic residents. For inquisitive tourists, spotting Michel Dancoisne-Martineau – the man who left Europe behind to settle on this isolated island and preserve Napoleon’s legacy – is a must-do, on par with scaling the steep, 900-foot Jacob’s Ladder in Jamestown or spending time with Jonathan, the 189-year-old giant tortoise, who is believed to be the world’s oldest living land animal and resides at the UK governor’s mansion.

“It annoys me,” he says, describing how islanders expect to know everything about you immediately but then leave you in peace, while visitors seem obsessed with the idea of simply spotting him.

“I’m just going about my work, but for some reason people feel the need to see me in person. Once, I agreed to meet a group because they were so persistent, but when we finally met, they had nothing to say – just wanted a photo. It's as if they think seeing the whale sharks, Jonathan, and me is all part of the same experience.”

Still, the life he has built is nothing short of extraordinary to most. In 2017, the long-awaited airport on the island finally opened, ending an era when reaching St. Helena meant a five-day journey aboard the British Royal Mail ship, the RMS St. Helena, from Cape Town.

Normally, he only leaves the island once each year, but due to the pandemic, he has been stuck on the island for the past two years without a single trip.

He buys only food on the island, using his annual trips to South Africa and France to stock up on clothes and other necessities.

“If you need anything beyond the basics, like coffee or other goods, you’ll have to import them from the UK,” he explains. Forget Amazon Prime – deliveries take around three months to arrive.

And despite the challenges, he has no desire to leave.

“I grew up in a small village in Picardy, so I’m accustomed to close-knit communities,” he says. “It’s not difficult at all – it’s just what I know. And I love the sense of community here. There’s a deep-rooted feeling that everyone is looking out for each other. That’s why I hold this place so dear.”

“I’ve built my home here and married a local, so there’s no reason for me to leave. And with Brexit, I feel even more connected to St. Helena than ever.”

Myths and magic

So, what about the man whose life has been intertwined with Dancoisne-Martineau's for over three decades? Was Napoleon a legend or a villain? A brilliant leader or a tyrant? And perhaps most intriguing, did the British assassinate him, or was his death due to stomach cancer?

Dancoisne-Martineau refuses to take the bait.

“You can think of Napoleon as a warmonger, a monster, a hero, or even a superhero – whatever your opinion of him is, it doesn’t concern me,” he says.

“I don't have a strong opinion either way. My role isn't to influence visitors' views – it's to preserve and present the home of a man who passed away just yesterday. If you despise him, you might be surprised that I'm not trying to change your mind at Longwood. I'm simply offering a perspective on the place.”

Over time, familiarity has not bred contempt, but rather indifference towards the subject.

“It's become my everyday life, so I've lost perspective, objectivity, everything. I focus on such a narrow view of the man. Every blade of grass has its meaning for me.”

Not everyone shares this calm approach. While most visitors come for the island’s marine life and seclusion, some are Napoleon enthusiasts – upset by Longwood's pristine state. Others attempt to steal artifacts that Dancoisne-Martineau has spent years recovering, many of which were taken back to France or scattered across the island.

And then there’s the empty tomb, a one-kilometer (0.6 mile) stroll down a romantic, lush hillside adorned with greenery.

“At first, I didn’t understand it,” he admits. “I thought it was strange to become the caretaker of an empty tomb. But it’s because the tomb is empty that everyone creates their own version of the man.”

“He’s no longer just a person; once an identity loses its physical form, it transforms into a myth. And naturally, a place like the Valley of the Tomb is the perfect backdrop to bring that myth to life, with nature enhancing the story. It’s a place where your imagination takes over. I love that.”

“It’s almost impossible to truly define Napoleon or pin him down, because everyone approaches him differently. It’s incredible how many people have their own feelings – whether they hate, love, or feel indifferent towards him. It’s as if every individual has their own interpretation.”

The tranquil life on the island

St. Helena is well-known as one of 14 British Overseas Territories, officially becoming part of the British Empire in 1875. While the UK’s Colonial Office was dissolved in 1966, Dancoisne-Martineau recalls that when he first arrived 19 years later, the island still had a noticeable colonial atmosphere, with many civil servants who had worked under the old system.

“Over time, that feeling faded and colonialism gradually disappeared,” he reflects, pointing to the 1982 Falklands War as a key turning point in this transformation.

‘St. Helena gradually took charge of its future, step by step. It's a tough road because the island lacks resources and relies heavily on the UK. But there's a deep, admirable determination to assert their identity, which is truly inspiring.”

Even in those early years, he says, he never encountered hostility due to his nationality, despite the long-standing French-British rivalry.

“That animosity faded long ago,” he reflects. “The few times I’ve faced criticism – which were so rare they barely count – have been from intellectuals in London, still trying to impose their postcolonial views on the island.”

“Locally, I’m just known as ‘The Frenchman’.”

However, after spending more time on St. Helena than he ever did in France, he admits he’s no longer the typical ‘Frenchman’ by any stretch of the imagination.

“I’m somewhere in between,” he responds when asked if he feels more like a Saint or a Frenchman.

“The French have a saying – ‘citoyen d’autre mer’ [citizen from across the sea], or even more poetically, ‘citoyen ultra-marin.’”

Though he neither likes nor dislikes Napoleon, he admits to being “captivated” by the man who “never gave up.”

“Most people in his position would have been consumed by despair and bitterness, but he showed resilience, always fighting, never, ever giving up,” he says.

But it’s the island of St. Helena itself, not its most famous inhabitant, that he feels the deepest connection with.

“I’ve fallen for the island and its people,” he shares.

“This is the place I’ve been searching for my entire life.”

1

2

3

4

5

Evaluation :

5/5