The Overlooked Filling Stations of America

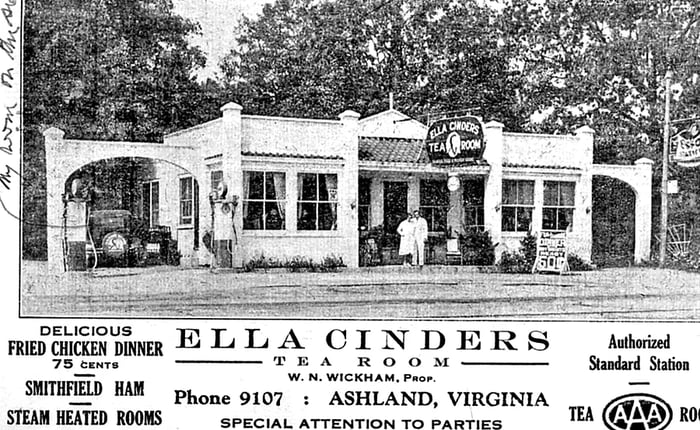

If you were driving from Washington, D.C. to Richmond, Virginia in 1935, you’d probably cruise along Route 1, the precursor to Interstate 95. With the Great Depression behind you, this trip serves as an opportunity to enjoy your new Plymouth PE Deluxe, just like Chrysler showcased at the Century of Progress exposition in Chicago. Cars back then averaged about 14 mpg, but 20 miles in, you notice your tank is low near Ashland, a historic resort town with Randolph-Macon College. Your party is also hungry. Just past Route 54, an Esso gas station sign catches your eye, leading you to Ella Cinders Tea Room, named after the popular comic strip from a decade prior. Fortunately, it’s Sunday, and they’re serving 75-cent dinners featuring fried chicken or Smithfield ham.

From the 1910s onward, tea rooms began to spring up along America’s expanding roadways. When the Virginia General Assembly included the 110-mile section of Route 1 between Richmond and Washington (originally the Richmond-Washington Highway) in the first state highway system in 1918, much of it was still unpaved. After rain, horses would sometimes have to pull cars through the mud. However, by 1927, the State Highway Commission (with help from convicts on the road force) had fully paved Route 1, widening it to four lanes in the early 1930s, coinciding with a surge in registered motor vehicles in Virginia, boosting business at Ella Cinders’ gas pumps and restaurant.

Tea rooms made their presence known with roadside signage, advertisements in early guidebooks, and sometimes featured whimsical designs, like a giant coffee pot that spouted steam from the roof. Some also functioned as inns or offered outdoor sleeping porches during the summer months. Many sold charming home decor and souvenirs, catering to various price points — “Look at the prices and watch the Fords go by,” noted one visitor in an early guest book. However, not all establishments were welcoming; Black motorists often found themselves excluded from segregated Mytouries and relied on guides like the Green Book, which listed friendly tea rooms owned by Black proprietors, such as Bagley’s in Sheepshead Bay, New York, and the Black Beauty Tea Room in Mount Olive, North Carolina.

The Ella Cinders Tea Room was probably named after a well-liked comic strip from the 1920s.

The Ashland Museum

The Ella Cinders Tea Room was probably named after a well-liked comic strip from the 1920s.

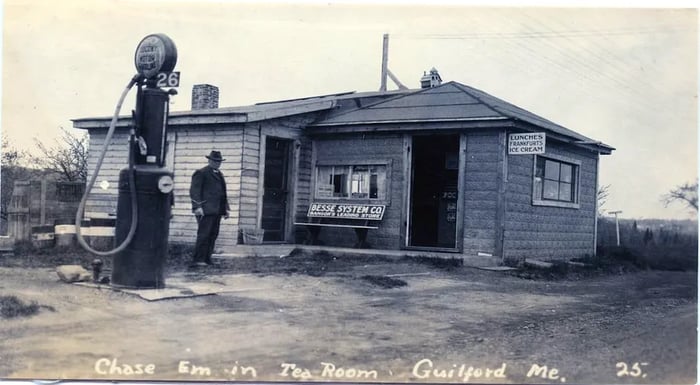

The Ashland MuseumAmong the various types of tea rooms, the most driver-friendly were those that combined a tea room with a gas station, like Ella Cinders. By the early 1900s, gas pumps emerged as a profitable venture for small businesses. Fort Wayne, Indiana, became known as the gas pump capital of the world, mainly supplying pumps to general and hardware stores before dedicated filling stations became common. Other roadside establishments also adopted these pumps, resulting in tea room filling stations popping up between major cities from Kentucky to Maine, and Missouri to Alberta, long before gas stations became recognized as culinary hotspots. For instance, Swan’s Service Station and Canary Tea Room in Pembroke, New Hampshire, offered waffles and special Sunday dishes like lobster and steak, while the Green Shutter Tea Room in Hopkinton, Massachusetts, featured a luxurious club sandwich. Other creatively named spots included the Gypsy Tea Room and Gas Station, Walker’s Jack O’Lantern Log Cabin Tea Room and Service Station, the Bungalow Tea Room, the Bird of Paradise Tea Room, and the Chase-Em-In Tea Room.

However, it was rare for these establishments to actually serve tea.

“The term ‘tea room’ can be misleading,” states Jan Whitaker, a restaurant historian and author of Tea at the Blue Lantern Inn: A Social History of the Tea Room Craze in America. These venues typically offered lunch and dinner rather than the European-style afternoon snack. Menus might include lobster and fried clams by the coast or barbecue in the Midwest, with desserts—especially ice cream—being bestsellers as electricity and refrigeration became commonplace. In the 1930s, The Alamo tea room in Moberly, Missouri, featured four-course Thanksgiving dinners, live dance music (“No Cover Charge — No Stags,” proclaimed one advertisement), and popular New Year’s Eve celebrations.

“There was not much profit in serving afternoon tea,” explains Whitaker. “What ‘tea room’ really signified was: Women are welcome here.”

The Coffee Pot restaurant in Roanoke, Virginia, attracted motorists with its eye-catching giant kettle on the roof.

The Coffee Pot restaurant in Roanoke, Virginia, attracted motorists with its eye-catching giant kettle on the roof. Tea rooms also served as restaurants, rest stops, and inns in rural regions like the Blue Ridge in Appalachia.

Tea rooms also served as restaurants, rest stops, and inns in rural regions like the Blue Ridge in Appalachia.Before tea rooms became popular in the U.S., the restaurant scene was dominated by hotels, bar-restaurants, and working-class taverns, which were primarily male-oriented. Only upscale establishments offered small, private dining rooms for women,” writes Cynthia Brandimarte, formerly of the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, in her Winterthur Portfolio essay, “To Make the Whole World Homelike: Gender, Space, and America’s Tea Room Movement.”

Inspired by a European trend, tea rooms began to emerge across American cities in the 1910s and 1920s, providing social venues for women and catering to the rising number of working women in the country. Then came Prohibition, which adversely affected male-oriented dining establishments that relied heavily on alcohol sales, while benefiting those selling nonalcoholic drinks, such as soda fountains and cafeterias. Tea rooms attracted both genders, but they were particularly appealing to women who had championed temperance.

As tea rooms gained popularity in urban areas, the automobile underwent rapid transformation from a novelty to a key aspect of middle-class life. Between 1911 and 1925, the global number of cars soared from approximately 600,000 to 17.5 million. Increasingly, these vehicles were driven by women—who, in an age where dining without a male escort was often frowned upon, needed welcoming places to stop and eat.

Members of the Greenwich Village Follies at the Mary Ryan Tea Room in Greenwich Village, New York, in 1925.

Getty Images

Members of the Greenwich Village Follies at the Mary Ryan Tea Room in Greenwich Village, New York, in 1925.

Getty ImagesHistorian Margaret Walsh from the University of Nottingham notes that in the early days of the automobile, there were significant uncertainties about how gender roles would intersect with car usage. Aside from a few notable figures like Emily Post and Edith Wharton, manufacturers were unsure if women would engage with the messy, hand-cranked vehicles at all. Automotive columnist C.H. Claudy, writing for Woman’s Home Companion, argued that electric cars, being cleaner and slower, were more suitable for women. In 1907, he described the electric car as a 'modern baby carriage,' a machine that a woman could operate with dignity for errands, shopping, leisurely drives, or to fulfill small social obligations.

Manufacturers of gas-powered vehicles had a keen interest in appealing to female drivers. Following the introduction of self-starters in the 1920s, General Motors proposed the concept of the two-car family in 1929, suggesting that women should own their vehicles. According to Walsh, 'Rural women, in particular, embraced the chance to escape their isolation by driving into town to shop, sell their farm goods, or attend local clubs.' More accustomed to horse-drawn carriages, these women found the idea of driving less intimidating than their urban counterparts, who were used to walking or public transit.

Inspired by the tea room craze in urban areas, rural business owners began adopting the term 'tea room' for their establishments—many of which were gas stations—to attract the new wave of urban 'autoists' who spent their summer weekends exploring the countryside for antiques or visiting resort towns. While many male customers dined at tea rooms (one even offered special meals for male chauffeurs), the tea room branding helped draw in mixed groups. As Whitaker explains, 'Restaurants linked to gas stations often had poor reputations. Calling it a tea room suggested a higher standard.' Many places were rough and unclean, and middle-class women with cars would not accept a shabby lunchroom.

To project a welcoming, homey vibe, owners transformed their tea rooms to resemble cozy homes, often repurposing old houses and residential structures. They featured roaring fireplaces, mantels adorned with crafts and pottery, oak furnishings, handwoven table runners, rag rugs, and Arts and Crafts-style decor—even selling decorative items as souvenirs right from the premises.

This domestic atmosphere allowed these establishments to engage in a subversive act: they not only served women but were frequently owned and operated by them. Whether they were wives seeking extra income, teachers on summer break, or church members raising funds, rural women found in tea rooms rare opportunities for economic independence. According to Whitaker, while it’s doubtful that many female proprietors managed the gas pumps themselves, they could work alongside husbands, male relatives, and employees.

The homey façade of tea rooms enabled these women to navigate societal expectations of staying within the domestic sphere, similar to how Mobil and Shell designed gas stations to resemble residential structures, whether they were bungalows, ranches, or Tudor revivals. Popular women’s magazines like Good Housekeeping, House Beautiful, and Woman’s Home Companion provided guidance on balancing cultural and commercial challenges. They served as practical guides on negotiating leases, managing finances, and overseeing kitchen staff.

Across rural America, businesses began installing fuel pumps to cater to the rising number of 'autoists' taking to the roads.

Guilford Historical Society

Across rural America, businesses began installing fuel pumps to cater to the rising number of 'autoists' taking to the roads.

Guilford Historical Society Urban elites frequently sought refuge from city life by taking leisurely drives through rural landscapes.

From the collections of The Henry Ford

Urban elites frequently sought refuge from city life by taking leisurely drives through rural landscapes.

From the collections of The Henry FordCertain magazines specifically catered to rural audiences, such as a 1922 article in Woman’s Home Companion titled, “Do You Own a Barn, an Old Mill or a Tumble Down House?” which encouraged women to transform dilapidated country buildings into tea rooms. These worn structures not only offered affordable options for budding businesses but also tapped into a wider cultural desire for pastoral escapism.

The charming, old-fashioned home appealed to the pearl-clutching advocates of the “Country Life” movement, who worried about the decline of traditional home environments in urban areas (ever since Modern Times, there has been a yearning for simpler days). Reformers, including President Theodore Roosevelt, who established a commission on the issue, aimed to enhance rural living conditions to prevent people from leaving the countryside for city life. Supporters of Country Life willingly invested in local entrepreneurs running tea rooms to help sustain the heartland, prompting these business owners to emphasize the wholesome country homemaker image to attract customers. As noted in a 1922 article from Woman’s Home Companion, “The more a tea house can distance itself from a commercial, money-driven atmosphere, the stronger foundation it will build for success.”

While nostalgic ideals might seem at odds with progressive automotive advancements, many in the Country Life movement advocated for improved roads to ensure rural happiness. Reformers collaborated with the Good Roads movement, which sought to expand the road network. Tea rooms served both initiatives by revitalizing dilapidated country structures, creating economic opportunities, and captivating city dwellers with romantic visions of idyllic rural life.

For example, Ye Green Lantern Shoppe in Gorham, Maine, promoted “rustic shelters for resting and dining,” along with tea room snacks and automotive supplies. Meanwhile, Ye Olde Common Tea Room in Lancaster, Massachusetts, offered “18 acres of land for camping and parking,” a “Gulf refining company filling station,” and “Supreme oil and supplies,” concluding their advertisement with a folksy touch: “house open the year ‘round.”

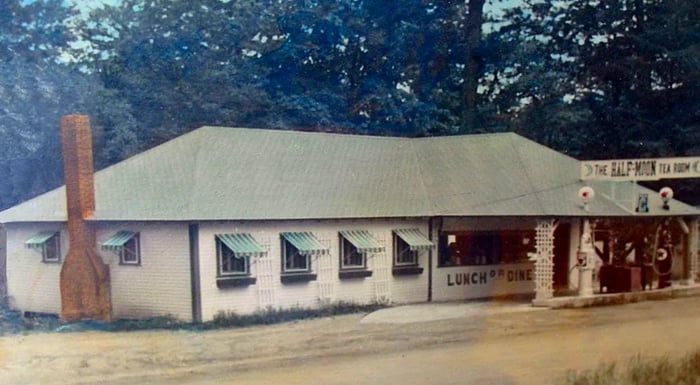

The Half-Moon Tea Room and pump station in Lake Winnipesaukee featured a restaurant, snack bar, bowling alley, and cabins.

weirsbeach.com

The Half-Moon Tea Room and pump station in Lake Winnipesaukee featured a restaurant, snack bar, bowling alley, and cabins.

weirsbeach.comBy the late ’50s, urban tea rooms had become outdated, failing to attract younger patrons. As post-war America thrived with roadsters, rural tea rooms faded alongside their city counterparts. They lost their clientele to fast-food giants like McDonald’s and A&W, which catered to the fast-paced lifestyle of modern travelers. Aside from a few exceptions like The Coffee Pot in Roanoke, Virginia, which reinvented itself as a roadhouse and music venue hosting acts like Willie Nelson, tea rooms at filling stations vanished. Over time, many of these establishments succumbed to natural disasters, neglect, and economic shifts, leaving little more than a few faded photographs as reminders of their existence.

Contemporary American tea rooms largely draw inspiration from an idealized vision of British nobility, serving afternoon scones and delicacies in upscale settings. The distinct American tea room experience of the ’20s and ’30s, characterized by fried chicken dinners, sleeping porches, and gas pumps, now seems peculiar. Like the vehicles they supported, these tea room filling stations were not pristine, yet they served as backdrops for the era's shifting culinary and cultural landscape.

In some respects, these venues remained exclusive, with segregation and class distinctions dictating dining access for some patrons. However, tea room filling stations also acted as hubs of cultural exchange, embodying Walt Whitman-esque contradictions: modern yet quaint, masculine alongside feminine, fast yet slow, commercial yet homely, rural yet urban. They encouraged drivers to explore, offered women opportunities to dine and work alongside men, and contributed to the acceleration of American culture — ironically rendering their own offerings seemingly outdated and absurd in an increasingly mobile society. They fostered demands that ultimately led to their decline.

Shortly after stopping for gas in Ashland, Virginia, in 1935, the Ella Cinders Tea Room began to stray from its original vision. A postcard from 1947 reveals that the tea room had eliminated its gas pumps (or at least ceased promoting them). This decision proved to be a misstep. Eventually, the building was demolished, and today the location houses an AutoZone. It does not serve tea.

Fact checked by Kelsey Lannin

1

2

3

4

5

Evaluation :

5/5