The roasted pigeon dish that might have reshaped the trajectory of modern Chinese culinary history

A large neon sign in blue and red floats above a narrow alleyway just off the bustling Nathan Road in Hong Kong's Yau Ma Tei district.

The sign boldly displays five Chinese characters that read ‘Tai Ping Koon Restaurant’—the iconic name of China’s first Chinese-owned ‘Western’ restaurant. Today, it remains one of Hong Kong’s oldest family-run dining establishments.

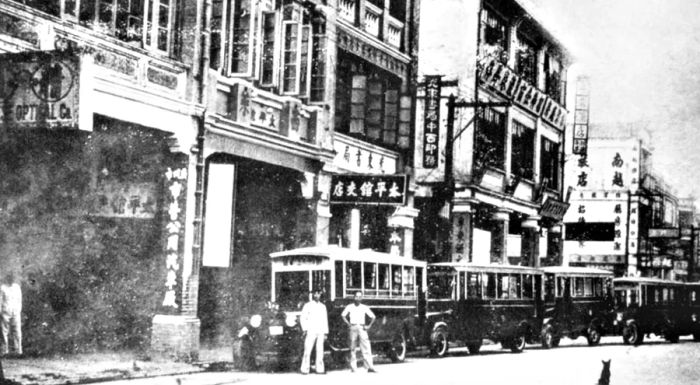

Founded in 1860 in Guangzhou, Tai Ping Koon originally had two locations in the city before relocating to Hong Kong in 1938 due to the Second Sino-Japanese War. The family moved due to political instability and now operates four branches across Hong Kong.

The Yau Ma Tei location, opened in 1964, is a popular lunchtime destination for office workers and tai tais. Its wood-paneled interiors, lace-draped windows, and leather booth seating evoke a sense of timeless sophistication.

Most guests come for one dish above all – the TPK Style Roasted Pigeon. Served by a bowtie-clad waiter, it comes with an unexpected side item: plastic gloves. After all, there’s no better way to enjoy this crispy, succulent bird than with your hands.

Though the dish is beloved by many, few of the diners savoring the roasted pigeon realize that this small, palm-sized bird may have had a profound impact on modern Chinese history.

The dawn of soy sauce-infused Western cuisine

Andrew Chui, the fifth-generation owner of the Tai Ping Koon restaurant chain, dedicated seven years to researching his family’s legacy by traveling to libraries across the globe.

“Tai Ping Koon’s significance goes beyond its 160 years of history; it’s an integral part of the nation’s story and has helped shape Cantonese culinary traditions,” says Chui, who has authored two books about his family’s restaurant business.

The origins of Tai Ping Koon date back to the aftermath of the First Opium War (1839-1842), when treaty ports were established in Canton – now Guangzhou – allowing Westerners to conduct trade. These ports also welcomed foreign-run establishments, including restaurants.

Typically led by foreign chefs and catering to Western sailors, these restaurants employed local cooks to assist in the kitchens.

“My great-great-great-grandfather Chui Lo-ko was hired as a cook in a restaurant operated by an American trading company. As a result, he became one of the first Chinese chefs trained in Western cuisine,” Chui explains.

However, the job didn’t last long. After a fallout with the trading company’s agent, Chui Lo-ko decided to quit.

With no money to his name, he was forced to find a way to survive using the only skill he had: preparing Western cuisine.

“And that was a problem,” Chui adds.

“At the time, Chinese people didn’t have much interest in Western cuisine – many of them didn’t even know what it was.”

Chui Lo Ko had an idea to prepare beef steak with soy sauce and sell it on the street.

By combining an unfamiliar ingredient with a familiar flavor, his fusion dish quickly gained popularity among the local Chinese community.

Once he had saved enough money, Chui Lo Ko opened the first Tai Ping Koon restaurant in 1860, naming it after its location on Tai Ping Sa Street in Canton.

This marked the birth of what is now known as soy sauce Western cuisine, a culinary style that has shaped Cantonese food culture for over a century.

The iconic roasted pigeon dish

Thanks to its distinctive offerings, Tai Ping Koon quickly became a popular spot for China’s elite, with notable guests such as Sun Yat-sen, the revolutionary leader and national hero, and the influential Soong sisters, who were said to have dined at the original Guangzhou location.

It was rumored that the eldest Soong sister, Soong Ai-ling, and her husband Kung Hsiang-hsi, one of the wealthiest men in China and a prominent Kuomintang leader, were such fans of Tai Ping Koon’s roasted pigeon that they hosted a special banquet for fellow party leader Chiang Kai-shek and his wife Chen Jieru.

What Chiang and Chen didn’t realize was that the banquet may have had a hidden agenda behind it.

Seated next to Chiang, quite deliberately, was Soong’s younger sister, the captivating Soong Mei-ling.

Squabs were not a common ingredient in China at that time. So, when roasted pigeon, a relatively new European-inspired dish, was served, Soong Mei-ling took it upon herself to show the guests how to properly eat the dish with their hands.

Legend has it that Chiang fell for the youngest Soong sister after the banquet. In 1927, he divorced his three wives and proposed to Soong Mei-ling.

The couple went on to become one of the most powerful and public political pairs in modern Chinese history, serving as the first president and first lady of the Republic of China in Taiwan.

Chiang’s ex-wife, Chen, later recounted the incident in her memoir, suggesting the pigeon dinner was a covert “husband-snatching” plot.

The enigmatic (non-)weddings

The pigeon dinner was just one of the many intriguing discoveries Chui made during his research on Tai Ping Koon’s history.

“These stories have been passed down through the generations with few details. I heard that Chiang and Soong returned to Tai Ping Koon in the 1930s for the roasted pigeon, as they were supposedly linked to the dish. But was that really the case?”

“It felt like detective work. I had to make sure I wasn’t fabricating anything. I wanted to prove that this story was truly about Tai Ping Koon,” Chui explains.

Chui visited every public and university library in Hong Kong. When that didn’t provide enough answers, he traveled to libraries in the United States, from Stanford to Chicago, to sift through their extensive Asia-focused collections.

“I read every book. Every single one. You have to either be extremely passionate or a bit crazy to dedicate seven years to this. I’m a crazy guy with passion,” says Chui.

In the end, he uncovered piles of news articles and stories in books that helped him piece together the puzzle.

There were also a few unresolved mysteries, such as the rumored wedding of former Vietnamese prime minister Ho Chi Minh and Tang Tuyet Minh, a Chinese midwife. This alleged ceremony was said to have taken place at one of Tai Ping Koon’s Guangzhou locations in 1926. However, the Vietnamese leader was never officially married.

“But if I had to choose one historical event related to the restaurant, I would love to travel back to the time when Zhou En-lai, the first premier of the People’s Republic of China, supposedly married Deng Ying-chao at Tai Ping Koon,” Chui shares.

In 1925, local media widely reported that Zhou En-lai and Deng Ying-chao had held their wedding at Tai Ping Koon. Given its upscale nature, hosting such a ceremony there would have been seen as inappropriate for a leader of the Communist Party.

The rumor was so pervasive that Zhou and Deng reportedly attempted to set the record straight multiple times in the following years, insisting they did not hold a ceremony at Tai Ping Koon. Instead, it was simply a dinner hosted by a thoughtful friend, aware that the couple, strapped for cash, hadn’t had a proper celebration for their relationship.

“Yet, the truth remains elusive. People continue to believe one side of the story or the other,” says Chui, as he pulls out a stack of two-inch-thick binders filled with old news clippings.

‘A vital part of Hong Kong’s history and culinary heritage’

Growing up in a family restaurant so deeply woven into history, Chui says it’s both an immense honor and a great source of stress, especially with the challenges Covid-19 has brought to the business over the past two years.

“In business, people keep going if they’re making money. If they aren’t, they close up shop. But for me, closing is simply not an option,” Chui says.

“It’s part of Hong Kong’s history and food culture. If we can keep the business running for just one more day, we’re extending the legend for another day.”

Tai Ping Koon continues to honor its traditions in many ways, including offering free housing and meals to their staff right next to their restaurants, in prime locations with notoriously high rents. This benefit was once standard before the 1970s, when transportation was difficult. Tai Ping Koon is believed to be the only remaining restaurant in Hong Kong still upholding this tradition.

The recipes have also been carefully preserved over the years.

“The pigeon is still prepared the traditional way: fresh pigeon, seasoned with our house-made soy sauce, and deep-fried upon order. The only difference is that, many years ago, we had our own pigeon coop in the backyard,” Chui shares.

When he was young, Chui recalls that his parents made him learn how to prepare the famous roasted pigeon in Tai Ping Koon’s kitchen.

Now, he brings his 13-year-old son to the kitchen regularly, teaching him how to make the enormous soufflé—another signature dish—by hand, hoping one day he will carry on the family tradition.

“I hope it will give him a sense of pride. I’m passing on the family stories about Tai Ping Koon to my children—just the fun ones for now to keep them engaged. Maybe I’ll share the tougher parts of the story with them later,” Chui laughs.

1

2

3

4

5

Evaluation :

5/5