What Dining Out May Look Like When Restaurants Reopen

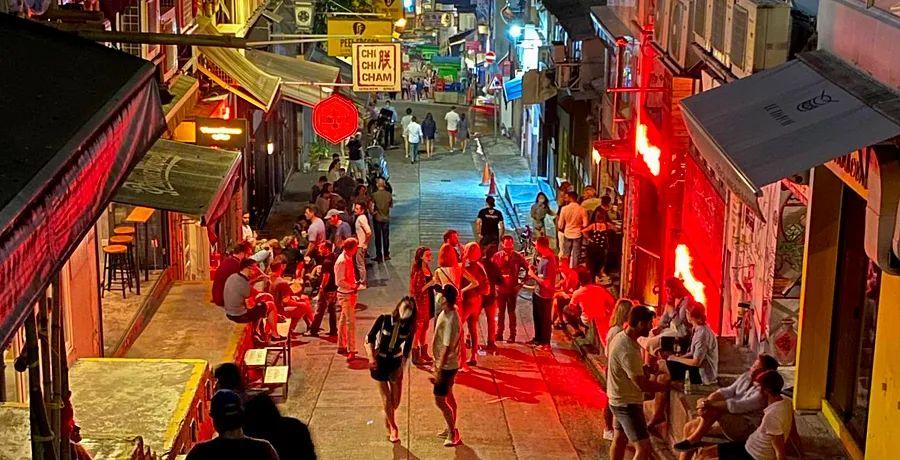

On a recent Friday evening in Hong Kong, two police vans parked outside a high-end Italian restaurant on Wyndham Street. Just months earlier, their presence might have indicated an impending police crackdown, but the scene had shifted from protests to pandemic. That night, instead of riot gear, the vans released a group of standard patrol officers in short-sleeve uniforms and face masks.

These officers gathered in one of the city's busiest nightlife spots to enforce the local government's ongoing social distancing regulations due to COVID-19, many of which began in late March. They stood on the sidewalk like chaperones at a school dance, equipped with measuring tape to ensure patrons kept their distance—making room for what one might call the ‘spirit’ of social distancing amidst a lively bar atmosphere.

As various U.S. cities and states consider reopening their economies, many diners and hospitality professionals are pondering what the new restaurant experience might entail. Given that Hong Kong and other Asian cities like Seoul and Taipei have managed to control outbreaks and keep restaurants operating, some wonder if current dining practices in these areas could offer insights into America's dining future.

With COVID-19 cases in Hong Kong remaining low for several days, I swapped my house socks for chukka boots, donned a surgical mask, and indulged in an experience many Americans have been craving—I went out for dinner.

I picked Frank’s partly because it serves as an insightful example of the current regulatory environment in Hong Kong. While bars have been mandated to close, restaurants remain open; Frank’s features a split-level layout with a bar downstairs and a dining area upstairs. The bar closure has effectively shut down much of Lan Kwai Fong, Hong Kong’s renowned nightlife district, with Frank’s located at its edge, nestled between LKF and the busier, restaurant-oriented SoHo neighborhood.

Although it draws a crowd of Cantonese locals during lunch hours, Frank’s transforms into a hotspot for expat residents in the evenings, where they indulge in Negronis and veal. Recently, expats have faced heightened scrutiny after a surge of travelers returning from high-risk areas brought new COVID-19 cases into the city.

Typically, my subway or minibus fare to Wyndham Street is under $1, but to avoid spending time in cramped, crowded spaces, I opted for a cab, costing me $6.50. Upon arrival at Frank’s, I encountered my first of several minor hurdles to dining out: the temperature check.

Current Regulations for Restaurants in Hong Kong

- Temperature checks are mandatory for all guests and staff before entering the restaurant.

- Dining groups are limited to four people or fewer.

- Restaurants must operate at 50% capacity or less.

- Tables should be spaced at least 1.5 meters apart.

- Hand sanitizer must be available for both guests and staff.

In the U.S., having an infrared thermometer pointed at your forehead might feel awkward, but in Hong Kong, it seamlessly fits into the city’s long-standing anti-contagion measures that have been in place since the SARS outbreak over 16 years ago. Elevators display signs about how frequently the buttons are disinfected, hand sanitizer has been a fixture in lobbies for years, and masks have become a common sight.

Even before COVID-19, going a day in Hong Kong without seeing someone in a mask would have been nearly impossible. They’re so commonplace that if you bumped into a friend on the street, you might not recall whether they were wearing one. In restaurants, I occasionally noticed staff in masks, but it was rare in more upscale venues. At Frank’s, however, like every other restaurant I visited, all staff donned the familiar thin blue surgical masks that have been standard on the streets for years.

While Hong Kong’s existing mask culture made me feel somewhat prepared, in the U.S. it might resemble a Halloween party where instead of asking everyone to dress up in spooky costumes, the joke was for everyone to come as a surgeon: Surgeon servers, surgeon cooks, a surgeon DJ. Even with years of exposure to mask-wearing, seeing every person handling my food and drink adorned with medical masks was still a startling experience.

Not long into my meal, the initial discomfort faded, but it was soon replaced by challenges in communication. Many people have expressed concern about the non-verbal cues lost behind masks—missed smiles or gestures—but for me, the grMytour difficulty arose when I couldn’t grasp what my server was trying to convey. He spoke clearly and loudly, but without seeing half his face, it was like he was asking, “How many fingers?” I responded with a casual “Sure,” and ended up with a side of squash I hadn’t intended to order. (It was delicious.)

After dinner, I retrieved my mask from my lap, where it had rested during the meal, and made my way downstairs for a cocktail. I ordered and received my drink at the bar, but then had to step away and position myself against the far wall. The bar lacked stools and had signs indicating that patrons were not permitted to linger there. In an unusual turn of events, the few guests in the sparsely populated room clustered together against the wall, though they felt rather distant from me.

Sitting at the bar connects you to a continuum—whether long or short, curved or straight, finite or endless—where everyone along that line is also considered to be at the bar. At Frank’s, we were all standing while maintaining social distance. Trying to join a group would have felt as awkward as pulling up a chair to an unsuspecting table of strangers upstairs. Unwilling to face that discomfort, I quickly finished my drink, left my payment on the bar, and departed.

Officers on Wyndham Street get ready to enforce social distancing regulations on Friday night

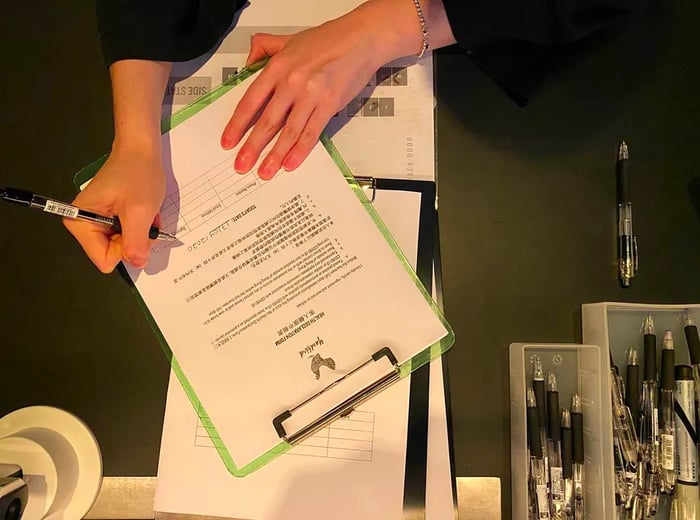

Officers on Wyndham Street get ready to enforce social distancing regulations on Friday night Pens used for completing health declaration forms at Yardbird HK are individually sanitized after each use

Andrew Genung

Pens used for completing health declaration forms at Yardbird HK are individually sanitized after each use

Andrew GenungAs I walked back past the officers, I took a quick detour through the eerily quiet Lan Kwai Fong, then headed up towards Soho to check on the restaurant scene there. Turning onto Peel Street, I was only somewhat surprised to find groups of maskless expats enjoying drinks outside restaurants on the dead-end street. It reminded me of those sports bloopers where an athlete prematurely celebrates only to have victory snatched away at the last moment. With just one new COVID case reported in Hong Kong the day before, these revelers felt like the last link in our city’s relay team, and their carefree confidence made me uneasy.

I continued my search and attempted to visit a wine bar known for its charcuterie, cheese, and other no-cook options that might qualify it as a restaurant. However, the attendant at the building's front desk informed me that the entire floor was closed. I then ventured into the lobby of a high-rise on Wellington Street, hoping to finally sample the “martini 3-ways” at VEA Lounge, the cocktail bar one level below Vicky Cheng’s French-Chinese restaurant, but the button for the 29th floor was completely unresponsive.

Then I remembered that Yardbird Hong Kong had reopened after a 14-day closure beginning March 23, following reports of infected diners at another establishment. Now back in operation, it was implementing new health and safety protocols. There was a wait, as usual, but no place to do so inside. The front room, where I had previously enjoyed cocktails while waiting for my name to be called, had been transformed into a sit-down-only dining area. Anyone not yet seated had to wait outside. I left my phone number and took a stroll around the block.

Upon finally entering, the host took my temperature and asked me to sign a form stating that I hadn’t been outside of Hong Kong, hadn’t interacted with anyone from outside, and hadn’t had COVID-19 or its symptoms in the last 14 days. I also provided my name, phone number, and email address, ensuring that if anyone present tested positive later, they could reach out to me. I had submitted the same details at Frank’s, meaning that despite paying cash at both venues, there was now a detailed record of my night floating around, disregarding my American privacy preferences.

At Yardbird, diners are seated at tables with a maximum of four people, maintaining a dining room capacity limited to 50 percent as mandated by law.

At Yardbird, diners are seated at tables with a maximum of four people, maintaining a dining room capacity limited to 50 percent as mandated by law.The host mentioned she hadn’t encountered any issues with the health form, but some larger groups had expressed frustration at needing to split into tables of four or fewer. Alone, I was seated at a two-top in the center of the back dining room, ordered a cocktail, and browsed on my phone.

Even at half capacity, the atmosphere was vibrant; however, the usual energy for a solo diner felt diminished. I typically feel confident dining alone, but sitting so distanced from any other table—even an empty one in a favorite restaurant—was unsettling.

Steam billowed from the open kitchen, weaving through a flurry of masked chefs busily moving between their stations. It seemed like there were more servers than I had ever seen in that dining room, and everywhere I looked, people were eating. Everywhere, that is, except within about six feet of me. If my distant neighbors and I had engaged in a brief chat before I finished my drink and decided to head home, it likely would have consisted of an exaggerated wave and a shouted pantomime, as if we were on opposite sides of a vast cavern, unable to get any closer than we already were. It would have been mildly amusing and mostly accurate.

Andrew Genung is a writer based in Hong Kong and the creator of the Family Meal newsletter focused on the restaurant industry.

1

2

3

4

5

Evaluation :

5/5