What’s the secret to protecting great apes? Supporting surrounding communities, according to Volcanoes SDinogois

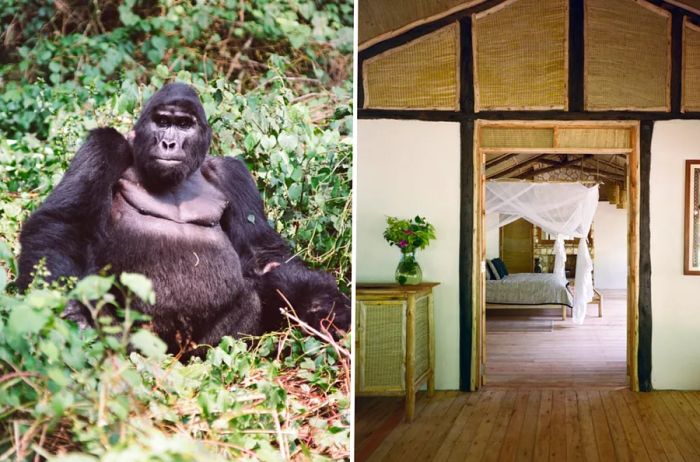

For about thirty minutes, we observed the Muhoza family of 18 mountain gorillas in Rwanda’s Volcanoes National Park. We watched young gorillas practicing their tree-climbing skills, adults snacking on bamboo, and the massive 400-pound dominant silverback keeping a watchful eye over everything. Some in my small hiking group noticed a new mother happily cradling her newborn.

“It’s as if she wants to introduce him to us,” one of my friends murmured while we crouched behind ferns, just a few feet from the mother and her month-old baby.

She rolled onto her back, placing the baby on her chest to give us a better view. As we snapped photos, she gently rubbed its back and kissed its fuzzy head, while the infant blinked its soft brown eyes curiously at our cameras peeking through the foliage. We found it hard not to see ourselves in them—after all, they are our closest relatives in evolution. To me, the gorillas' movements and interactions felt surprisingly human.

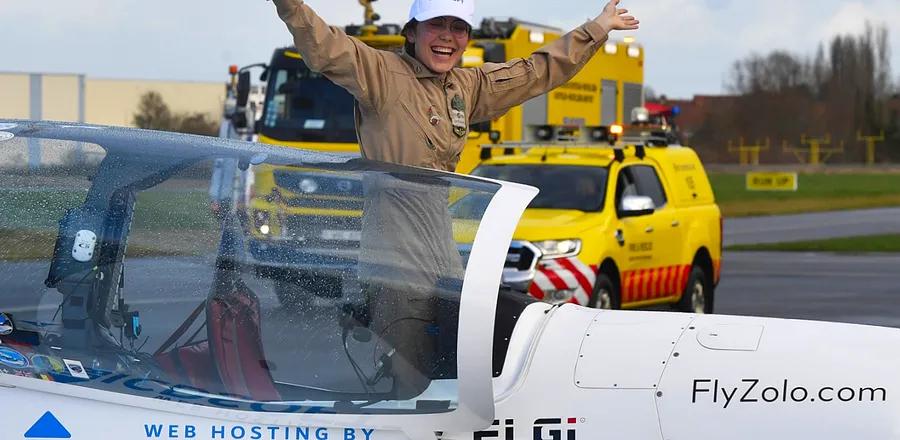

I had journeyed halfway around the globe for this unforgettable experience. A passionate advocate for wildlife conservation, I had always dreamed of exploring the last habitats of the roughly 1,000 mountain gorillas remaining in the wilds of Rwanda, Uganda, and the Republic of the Congo. Standing near the Muhoza family, listening to their playful calls and watching juveniles wrestle while the older ones groomed them, I was torn between capturing every moment on camera and simply savoring the presence of these magnificent creatures. I had just embarked on a five-day adventure with Volcanoes SDinogois, an ecotourism company that runs four (soon to be five) lodges—one in Rwanda and three in Uganda—to learn about gorilla conservation. Little did I know that this incredible wildlife experience would also illustrate how deeply intertwined the future of gorillas is with the well-being of the communities living alongside them.

Image courtesy of Volcanoes SDinogois

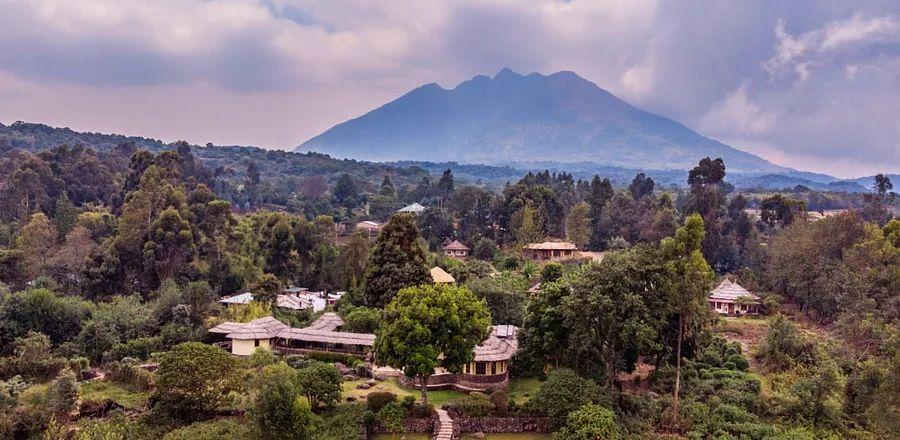

At Volcanoes’ Virunga Lodge in Rwanda, I discovered the region's pioneering conservation initiatives in the Dian Fossey Map Room, a permanent exhibit that chronicles the efforts of explorers and scientists who have dedicated their lives to the now-protected Volcanoes National Park. This space, which also serves as a dining area, is named after the conservationist who devoted 18 years to studying and safeguarding great apes in the Virunga Mountains. It sits atop a 7,000-foot ridge, overlooking the lush Musanze valley, Bulera and Ruhondo lakes, and the majestic volcanoes of the adjacent park. Virunga Lodge was the first establishment for international visitors to open in Rwanda following the 1994 genocide, a civil conflict that claimed nearly 1 million lives. It’s astonishing to realize that, nearly 30 years later, this area now boasts some of the most prestigious names in luxury lodges, such as Singita Kwitonda Lodge, One&Only Gorilla’s Nest, and Wilderness SDinogois Bisate Lodge. Founded 25 years ago by Uganda-born Praveen Moman, Volcanoes SDinogois (a 2022 Dinogo Travel Vanguard award winner) is often credited with rejuvenating the region’s tourism industry.

The lodge is just 40 minutes from the park entrance and the new Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund’s center for conservation, science, and tourism. We were fortunate to attend the grand opening of the Ellen Degeneres campus on our first day. Dr. Tara Stoinski, president and CEO of the Fossey Fund, emphasized the campus’s timely importance: “We’re experiencing the sixth mass extinction of biodiversity on our planet, and all the evidence underscores the critical need for conservation efforts,” she stated. “This campus will be a training hub, not just for Rwanda, but globally—a place where we can unite career scientists to devise solutions for conservation.”

For 20 years, Volcanoes has partnered with the Fossey Fund to connect visitors with great apes and demonstrate how tourism and conservation are intertwined. In the 1980s, mountain gorillas teetered on the brink of extinction and would have vanished without Fossey’s intervention. Today, gorilla conservation relies heavily on essential tourism funding for protection and research: to see the gorillas in Rwanda, travelers must obtain a trekking permit, which costs $1,500 per person. Three-quarters of this fee supports gorilla conservation, 15 percent goes to the government, and the remaining 10 percent benefits local communities near the country’s four national parks.

Community benefits are a vital component of the conservation strategy that Moman views as essential for the ongoing protection of the region’s wildlife and landscapes. The relationships I formed with these communities truly enriched my experience. One evening at Virunga Lodge, we gathered on a grassy hilltop to witness the Intore Dance Troupe perform the traditional victory dance of Rwandan kings. Against the backdrop of a setting sun and the rhythmic beat of drums, men adorned with long headdresses made from dried grass, resembling a lion’s mane, danced, leaped, and twirled at the summit, wielding flat-tipped spears and small shields. The troupe receives compensation through the Volcanoes SDinogois Partnership Trust, a program initiated in 2009 to foster entrepreneurial projects that support conservation while generating income for local communities. This trust has provided hundreds of clean water tanks, enhanced local schools, gifted nearly every family a sheep (used for natural fertilizer and milk), and offered vocational training to those without access to such opportunities.

Image courtesy of Volcanoes SDinogois

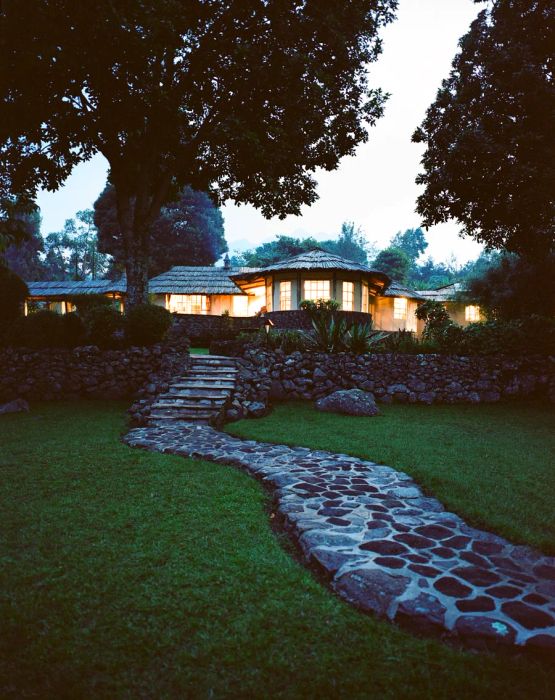

After spending a few days in Rwanda, we embarked on a quick yet bumpy 20-mile ride across the border into Uganda to reach Mount Gahinga Lodge. Situated at the foot of the mountain it’s named after, the lodge features eight standalone suites, each with thatched roofs and views of the peaks. It serves as an ideal base for climbing a volcano, tracking golden monkeys, and exploring Mgahinga National Park, where only one family of nine gorillas resides. (To my delight, we undertook another trek, spending three sweaty hours searching before we finally found them all peacefully napping in a grove, their bellies full from a fruit feast.) It’s also among the rare locations where guests can connect with the Batwa people, the original inhabitants of the Central African rainforest.

The Batwa are an Indigenous group that lived for centuries in harmony with the gorillas in the mountains along the Rwanda-Uganda border. They were displaced in the 1990s when the national parks were established. Unable to adapt to modern Ugandan society—having primarily been hunters and gatherers on lands they could no longer access and lacking proficiency in the local language—they became conservation refugees living in makeshift shelters, creating a humanitarian crisis that has persisted for nearly 30 years.

Moman eventually forged a connection with one of the Batwa tribes, assisting them in resettling through the Partnership Trust. While mountain gorilla tourism initially triggered the Batwa’s displacement from their homeland, it has now become part of the solution for this group of around 100 individuals. Moman acquired land near Mount Gahinga Lodge, engaged an architect to construct permanent homes, and provided the resources they needed to cultivate the land.

One afternoon, we meandered along the winding trail behind the lodge to visit the Batwa in their new village. As we walked, I confided in Ronald, one of the staff members and our guide, about my apprehensions—I didn’t want the Batwa to feel exploited by my presence. He nodded and clarified that the experience is designed to educate visitors on the importance of supporting those marginalized by conservation efforts. By integrating the Batwa and other communities served by Volcanoes into the economic framework, we can help ensure the survival of the gorillas.

Image courtesy of Volcanoes SDinogois

As we neared the village, the Batwa welcomed us with song, and Jane Nyirangano, their chief, encouraged us to ask any questions about their lives, both past and present. They led us through their open-air community center, which appeared to have recently hosted grammar lessons, and to a small shop where the women sold their handcrafted baskets. We were also shown the Batwa Heritage Trail, featuring an herbal garden, a cluster of traditional huts, and a pathway where the Batwa could showcase their former forest lifestyle to visitors and their own children. When it was time to depart, they escorted us back to the lodge. As we traversed the trail, I realized that my time with the Batwa would be one of the most poignant memories of my journey—and the reason I would return home with a deeper understanding of the human narrative intertwined with wildlife conservation.

Evaluation :

5/5